CALDWELL, Idaho — By the time he was arrested earlier this month for going on a drunken rampage through his parents' home, breaking their possessions and flinging a beer can at a family member, the young man had already been convicted of 18 separate misdemeanors.

Eight different times, he no-showed at court dates.

Nine times, he violated his probation.

On his pretrial risk score, a metric designed to predict how likely a defendant is to commit more crimes, he scored an alarming eight out of ten, Deputy Prosecutor Kimberlee Bratcher noted.

But today, he was as good as it was going to get.

More people, more problems

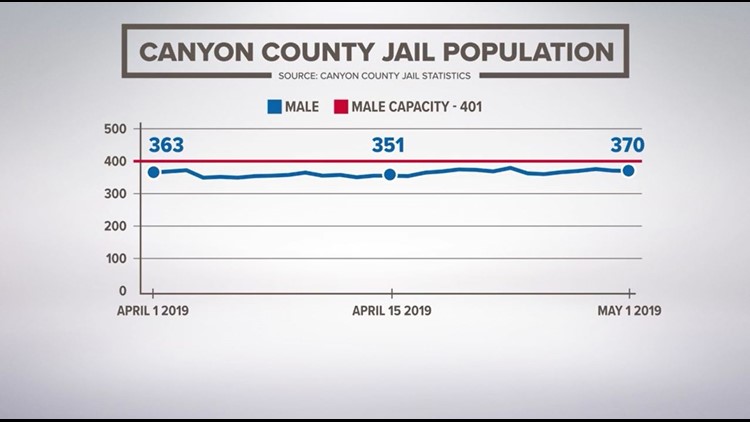

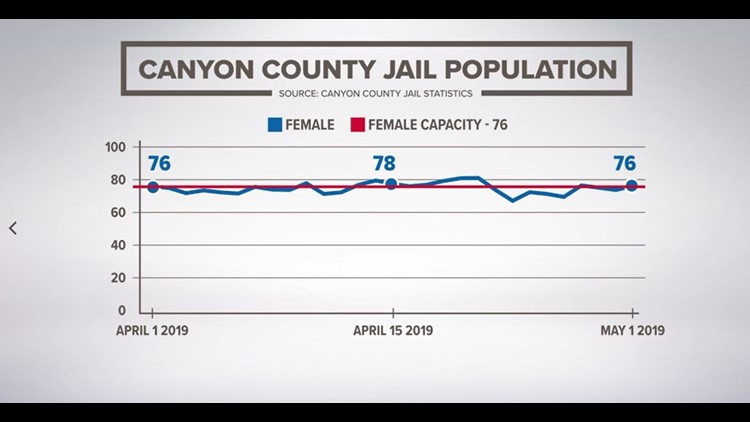

Overcrowding at the Canyon County Jail has plagued the county for years.

The 321-bed Dale G. Haile Detention Center officially opened in 1993, when the population of Canyon County hovered around 90,000. Now, the county's population sits at 217,180.

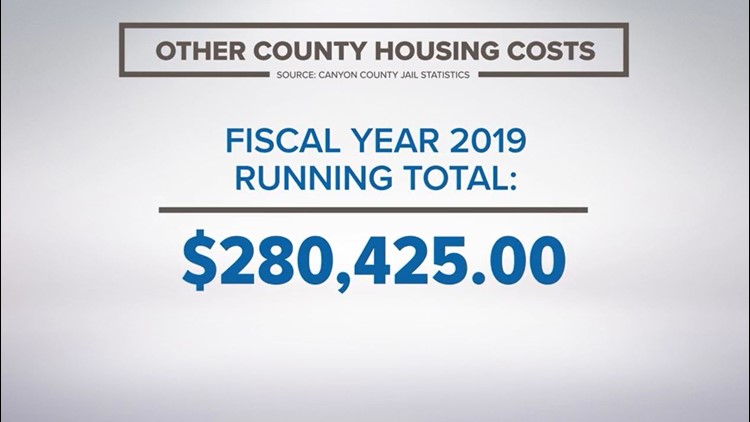

Attempts to alleviate the lack of space — including moving some inmates into a tent facility and paying out more than $1 million to send offenders to other jails — have fallen short. As a result, the county has been left scrambling to figure out how to house more offenders as the number of inmates balloons.

VOTER GUIDE: See what's on your ballot for the May 2019 election

Officials are hoping Canyon County residents will vote May 21 to pass a bond that will allocate $187 million to build a new jail. Three previous attempts at a jail bond have failed.

In the meantime, the county has resorted to simply letting some offenders out of jail entirely ahead of their trials, relying on an increasingly high-stakes calculus to decide who gets to walk out the door.

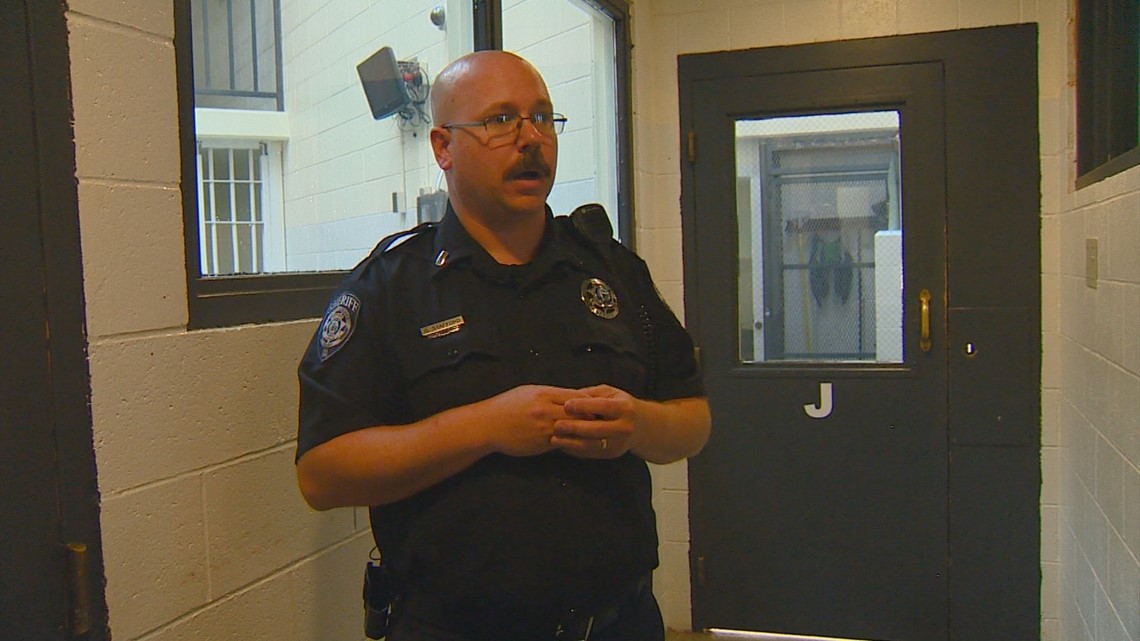

That job has fallen to Bratcher, a prosecutor for Canyon County, and Canyon County Sheriff's Office Sgt. Travis Engle, who oversees the jail's alternative sentencing program. The duo meets up daily to pore over lists of current inmates that could be cut loose to free up space for people accused of more serious crimes.

Those decisions have gotten harder.

Bratcher and Engle have already moved to release many of those arrested for lower-level crimes, such as misdemeanor marijuana possession or driving offenses. That leaves the pair continually selecting the best candidates from a pool of people charged with increasingly significant offenses.

"Ultimately, we're sitting here flipping a coin deciding who is worse or better to get out of custody," Engle said. "When I got into law enforcement, I didn't sign up for that."

Someone charged with a serious violent crime — like rape or murder — would never make the shortlist to be considered for release, Bratcher said, along with those accused of domestic violence, assault or DUI.

They have had to relax their guidelines before. A person who had violated his or her probation, or someone charged with felony possession of heroin or methamphetamine never used to make the list.

But after a while, there just wasn't anyone else to let go.

'Atrocious' blind spots, no room to grow

Jail Lt. Dale Stafford, who has spent 15 years working at the Canyon County facility, knows all about the toll of those complicated mathematics.

A busy day can see patrol cars holding recent arrestees stretched ten-deep around the corner. New inmates sometimes end up sleeping on the floor until they can be processed, or held in the booking area until a spot elsewhere opens up.

The need to keep a variety of people separated - men and women, codefendants on the same case, different classifications of offenders - adds another daily level of complication.

"It's kind of like three-card Monte - you are playing shuffle, trying to figure out where you are going to put somebody," Stafford said.

The lack of space also means there can be a long wait to place inmates into protective custody or other specialized units. Deputies routinely tell inmates who get in fights or break jail rules that they will be sent to the more-restrictive disciplinary housing as punishment.

Eventually. When a cell is available.

Space is not the only issue in the current jail building. In a recent tour through the facility, Stafford pointed to "atrocious" blind spots in corners and under stairwells, exposed pipes, and bathrooms added in as an afterthought - including in the hubs from which deputies keep an eye on inmates in 12-hour shifts, where a single toilet is separated from the rest of the cramped station by a plastic sheet.

Simply adding on to the existing building is a non-starter, he said.

"We have cracks in the floor from concrete not being appropriate depth, and we have issues with structural engineering," he said. "You can't build on [and] you can't build up, because it's not sound enough to do that."

'It's always a gamble'

The young man accused of smashing up his parents' things was the last name on the day's list, and Bratcher was still scrolling through his long list of prior arrests. Escape. Drugs. Domestic battery.

"With that history, he's not going to do well on pretrial release, but the crime is a misdemeanor, and we're how many over I saw on males today? Ten?" Bratcher asked. "15?"

"Yeah, roughly," Engle replied.

She scans the man's file again, and makes a decision.

"OK, well he's pretty much not going to come back to court, but I'd rather keep a felon," she said. "I'll work on getting him out."

---

It's not exactly a get-out-of-jail-free card.

A judge has to sign off the inmates Bratcher and Engle recommend letting out, and can elect to block the release entirely. The defendant's charges don't disappear. Often, those released are subjected to pretrial conditions, which can include GPS monitoring, alcohol restrictions, and mandatory check-ins.

Still, Bratcher said, the time span between agreeing to recommend an inmate be released and that person walking out of the jail is typically only a few hours.

At the end of the day, Bratcher and Engle go home too. They hope they made the right call. They hope nothing happens.

"It's rough, to go home and know that you've done that. That you had to let somebody out of custody because I have somebody else that I need to keep in," Engle said. "It's not like I can just go home and shut it off. You're thinking about it all the time."

Bratcher agreed.

"It's always a gamble, and it's nerve-wracking," she said. "We obviously don't want to let the wrong person out who would go and do something."

Every gambler knows there will come a day when their luck runs out.

None of the people Bratcher and Engle have green-lit for release have gone on to kill someone, she said, knocking her knuckles against her wooden desk.

"That's the whole concern, right?" she says. "It hasn't happened yet, but it's a matter of time."

"We know it's gonna happen," Engle agreed.

One tent, 122 offenders

The cloth walls of the jail tent rebound like a stretched trampoline when you tap on them. There used to be insulation filling the gap between interior and exterior fabric, Stafford said, but it long ago settled down at the bottom. The tent, originally meant for work-release inmates, was only designed to be in service for 20 years. It's about a decade past that.

Inside, 122 lower-risk inmates mill around the single room, walking laps, reading, talking, or lying on their bunks. Three deputies total are placed in the tent as well, tasked with keeping order.

It's a big ask. There is constant noise and activity, and the close quarters mean inmates are continually getting on each others' nerves. Stafford said the dormitory-style design is more difficult to manage than a traditional cellblock, and creates real security concerns.

The facility has been the site of multiple escapes, with inmates forcing open doors, slitting a hole in the tent with razorblades, or scaling the fence bordering the tent.

Stafford says he understands the public’s reluctance to back a jail bond. As a county taxpayer, he's not keen to see his bill go up either. But Canyon County's need for a new jail is indisputable, he said, and growing more urgent by the day.

"You pay for it now, or you pay for it later. It just depends how you want to pay that bill," he said. "It's either going to be in the taxes, or it's going to be in your property value, or it's going to be your rights get violated."

Officials estimate the bond, which would pay for a new 1,055-bed jail west of Caldwell, will cost about $94.43 a year per $100,000 in property value, or about $7.87 a month.

Ignoring the jail's inability to contain all of the county’s inmates is not an option, Stafford said.

"It doesn't become personal until it becomes personal," he said. "They’re humans too. And it's all nice to say until it’s your mom, your dad, your brother, your sister, your son, your daughter that’s in jail. Then you care. Or, it's your house that gets burglarized. Then you care."

Canyon Co Jail costs, population

Bratcher and Engle say he's right.

The drug addicts who fall within the parameters of who is deemed acceptable to let go have to get the money for narcotics somewhere, Bratcher said, pointing to the recent rise of home invasions in Canyon County.

"You look at these crimes and some people may say, 'well, possession of a controlled substance isn't necessarily a crime of violence,'" she said. "But it can lead to crimes of violence."

There will come a point, Engle said, when even the stopgap methods Canyon County is using now - letting people go, shipping them elsewhere - won't be enough.

"If we don't do something different than we're doing right now - we can't keep doing this," he said. "We're just going to have to keep doing this every day, and it's going to get worse and worse, who we're letting out."