BOISE, Idaho —

It has been nearly a decade since the state of Idaho has executed someone on death row.

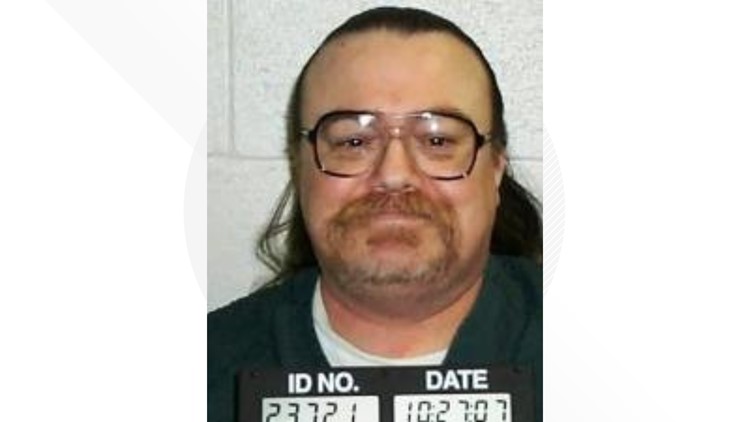

However, one of Idaho’s longest-serving death-row inmates has made the headlines. Gerald Pizzuto has been on death row for three decades, but earlier this year, the Commission of Pardons and Parole voted to reduce his death sentence to life in prison since Pizzuto is terminally ill and is no longer a threat to anyone.

The case is still being litigated, but it left us at KTVB with a few questions:

- Why are some people on death row for decades?

- What does the death penalty look like in Idaho?

- Who is involved when someone is sentenced to death?

Idaho State Death Row

There are 27 states that currently authorize capital punishment in the United States, including Idaho. Three of those states, Pennsylvania, California, and Oregon, have a moratorium on executions.

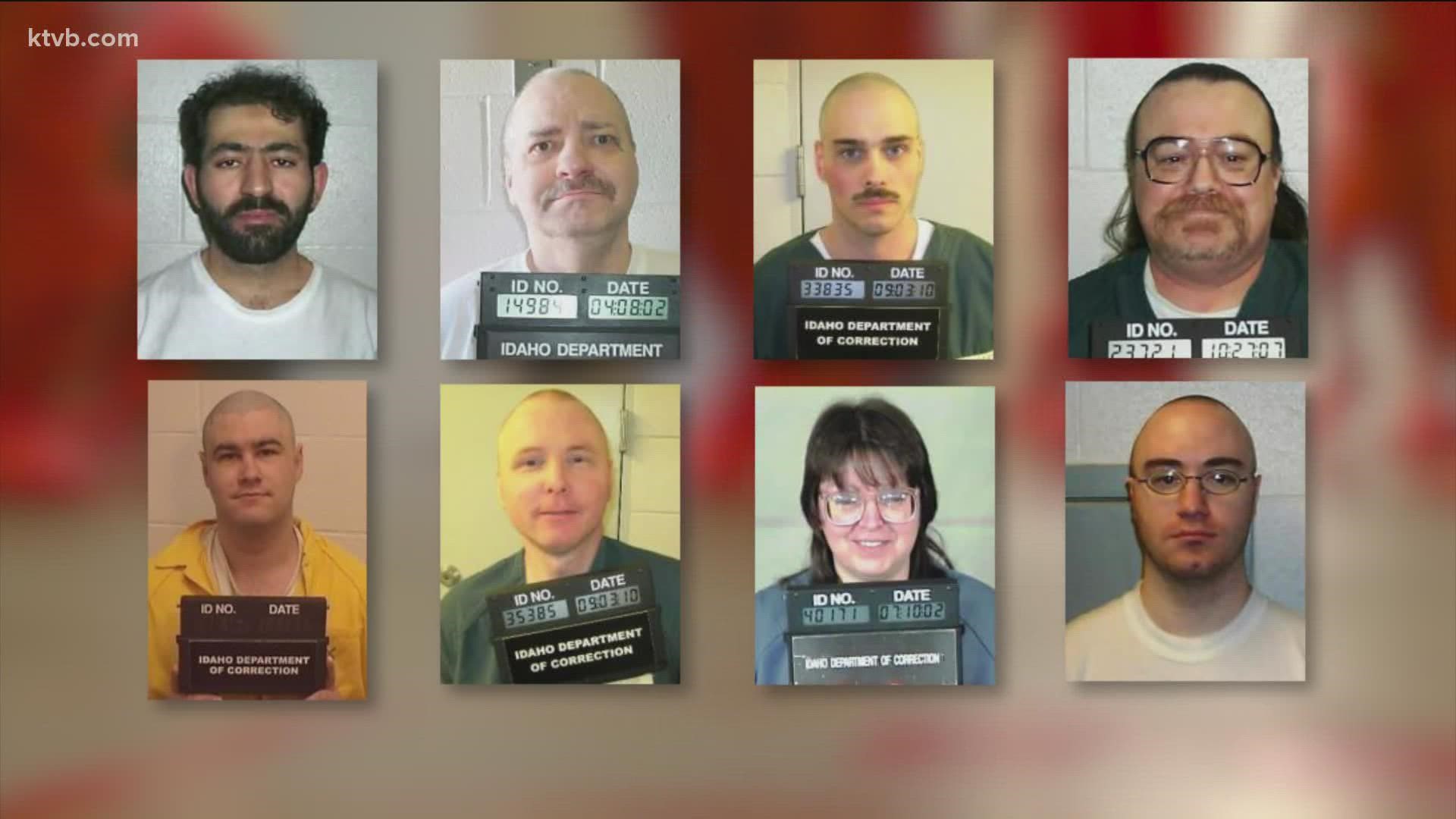

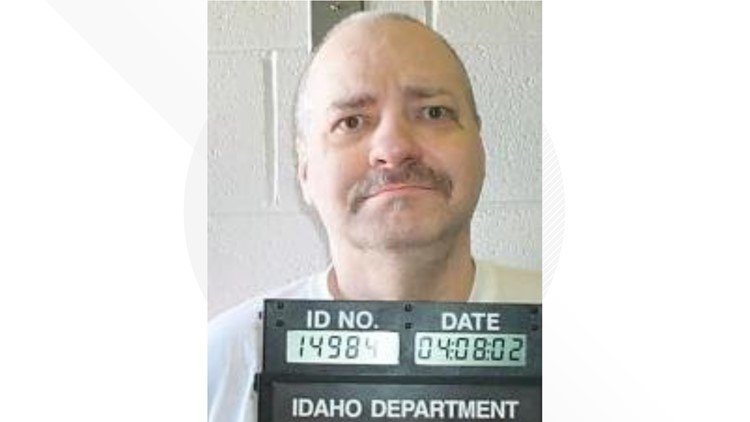

Eight people are currently on Idaho’s death row. Including one female, Robin Row, and Idaho’s longest-serving death row prisoner, Thomas Creech, who was sentenced four decades ago in 1983.

Idaho Death Row Inmates

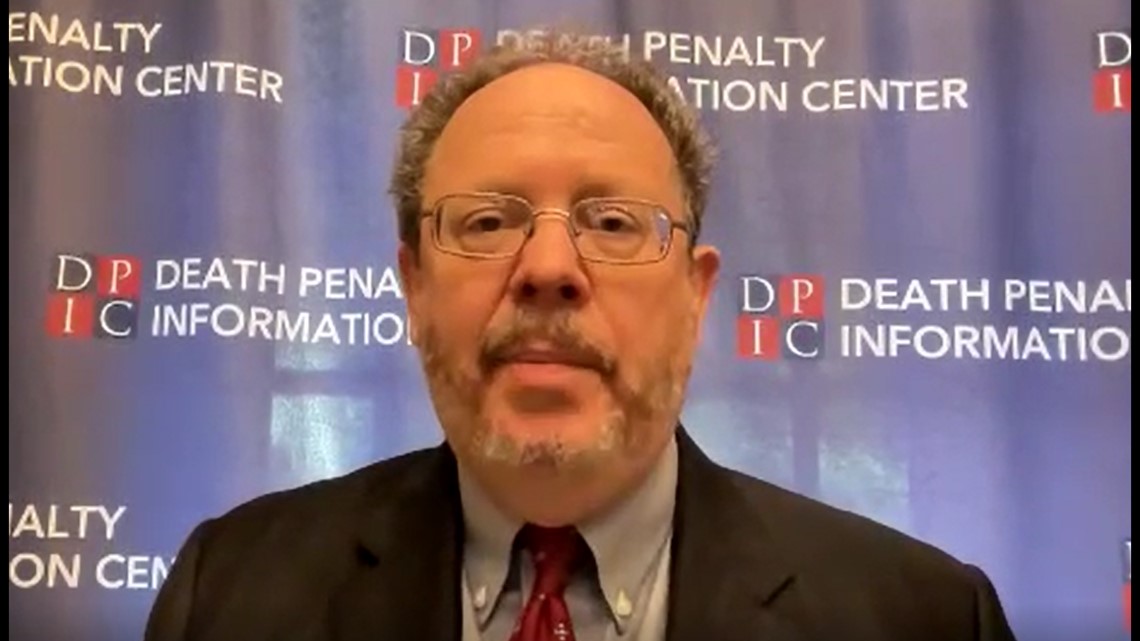

“The death penalty has been taking longer and longer and it's gotten longer over time,” said Robert Dunham the executive director of The Death Penalty Information Center, a non-profit that does not take a stance for or against capital punishment. “In 2000, the Bureau of Justice Statistics said that the average amount of time that an individual was on death row was 7.7 years. At the end of 2020. The Bureau of Justice Statistics said the average was 19.4 years.”

The Legal Process

L. Lamont Anderson, the chief of the Capitol Litigation Unit in the Idaho Attorney general’s office, explained the legal process of execution.

“If a death sentence is imposed, then they have what we call post-conviction relief,” Anderson said.

From there, it can go through a complex route of higher courts, with some making it all the way to the United States Supreme Court.

“Within that timeframe, you can have successive post-conviction petitions that get the federal proceedings sidetracked. And so, to do the review that is involved, at least in Idaho, it just takes a very long time,” Anderson said.

So long, that Anderson is still working on some cases he first started when he took the job 25 years ago.

“We have eight death sentence murders. And less than half of those are what you would call new cases. The others are old, from the 80s 90s, early 2000s,” Anderson said.

In 2014, the Idaho Legislature’s Office of Performance Evaluations conducted a study of the financial costs of the death penalty. The evaluation found that the death penalty costs more than sentencing a person to life without parole because capital cases take longer to resolve than non-capital cases.

Lethal Injection

The last time Idaho executed someone on death row was executed in Idaho was in 2012 when Rochard Leavitt was put to death by lethal injection. His execution came just seven months after Paul Rhoades was executed.

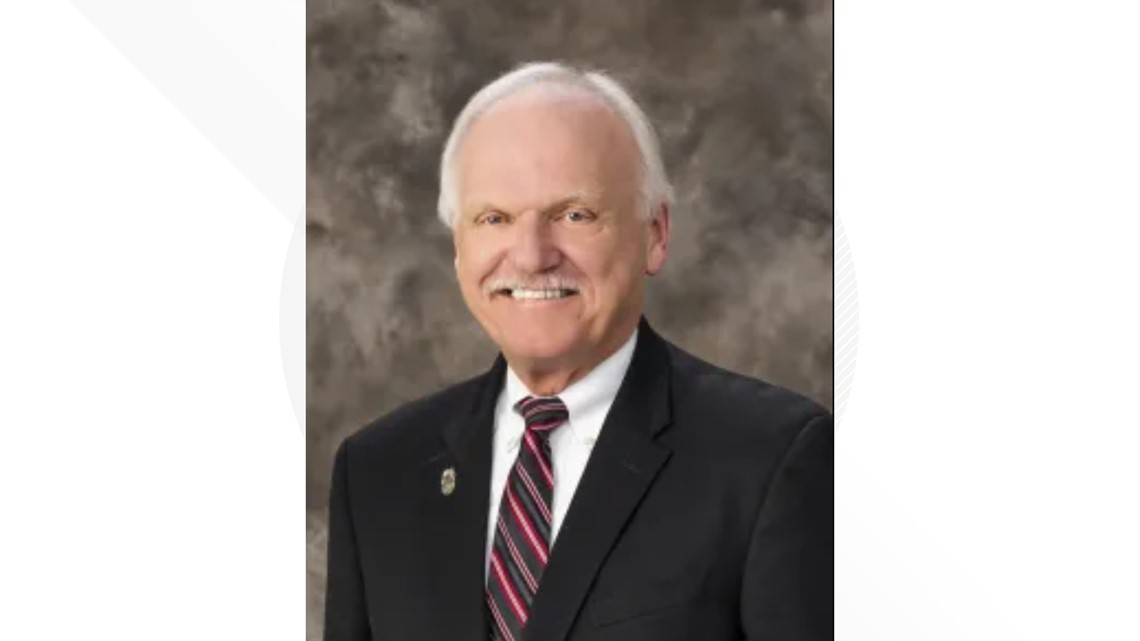

“It was very intense, it was very challenging. There's so many aspects that play into it,” said Brent Reinke, the Twin Falls County Commissioner, who was serving as the director of the Idaho Department of Corrections when the two executions took place.

“In that time period, it was very difficult to be able to acquire the necessary drugs to be able to carry out the execution,” Reinke said. “And so that was a very daunting task, working with a lot of other states and a lot of other jurisdictions, trying to understand where we might be able to acquire those, how that might be done. And then we did a tremendous amount of rehearsing, leading up to that particular event.”

Obtaining those drugs sparked controversy and a call for more transparency after reports came out saying that states, like Idaho, sent employees to pharmacies in other states, with suitcases full of cash to pick up the drugs to be used in the execution. Bringing up questions about the lethal injection drug suppliers, as well as the nature of the drug and its efficacy.

“Idaho also has as a very serious issue, the question of secrecy and public accountability,” Dunham said. “The state has said that it's had difficulty in obtaining execution drugs. But when you look at the state's practices, you understand that it's engaged in cloak and dagger activities in trying to obtain the drugs.”

Last month, Idaho Governor Brad Little signed a bill into law that increases the secrecy surrounding Idaho’s lethal injection drugs. Which stems from what happened nearly a decade ago. Supporters of the bill said it is the only way Idaho can continue carrying out lawful executions because no suppliers of the chemicals will sell the drugs to the state without guaranteed confidentiality.

Looking back at the executions, Reinke called them the most difficult task someone can handle in the Idaho criminal justice system.

‘It's something that is permanent, and we want to do that, as I've indicated, with as much professionalism, dignity, and respect, which is what our governor asked of us. That's what we provided, and I'm very proud of the men and women that carry that out,” Reinke said. “We made sure that we dotted every I and crossed every T so that we could carry out as the governor wished.”

Executions And The Media

As a part of Idaho’s policy for executions, media witnesses are present on behalf of the public. Associated Press correspondent, Rebecca Boone was one of those witnesses for the execution of Leavitt and Rhoades.

“It's an unusual thing in our state, compared to some other states, but it's always kind of there in the background, because you never know when the next one is going to occur,” Boone said.

Boone was present to monitor the execution and explain what happens, so the public can then decide how they feel about executions and how the state carries them out.

“They're quite somber. They're quite serious. You're seeing somebody be put to death, it's hard to explain. It's hard to explain the feeling that you get when that happens, because it is so far beyond the norm of what we experienced,” Boone said. “ There's the human element, you can't get away from, the fact that this is somebody who comes into the chamber and you know, they know they're about to die and you know they're about to die and everybody else knows they're about to die, and then there's families who are hoping this will be closer to the, you know, the toughest, most awful moments of their lives like it's just all-around a very weighty moment.”

Idaho Innocence Project

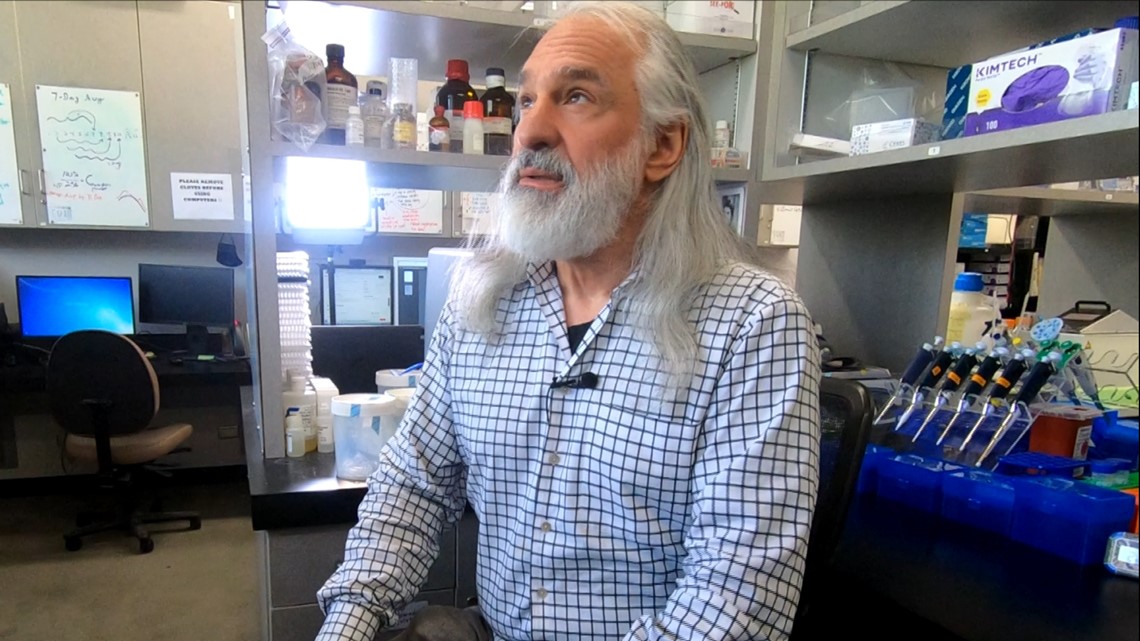

“We've had over 1500 executions, since they made it legal again, in 19 76. In this country, we've had 187 People who are on death row exonerated and found innocent. So if we had rapid justice, and I think we do in some states, those people would have all been dead, because it takes 10 to 20 years to get someone out,” said Dr. Greg Hampikian the co-director of the Idaho Innocence Project and director of the Forensic Justice Project at Boise State.

With every execution, Dr. Hampikian said there is a risk of a mistake.

“I'm not here to debate the morality, just those numbers. And if you execute someone, there's nothing that all this equipment can do to restore anything to that person,” Dr. Hampikian said. “I want them to look at the numbers because I, you know, I think while we have a gut reaction to crime, and it's horrible, you know, I have to see a lot of it. The numbers tell us that we do make mistakes. And do we want those to be irreversible mistakes?”

While the debate about the morality of the death penalty continues, many involved in the process agree that transparency is vital to the process.

“It's important that people really understand what that's all about,” Anderson said. “So they can make an informed decision regarding whether they do or don't support the death penalty, or just don't care one way or the other.”

Anderson also said the most challenging part of the process is having to tell the family of the parties involved when a person has to be re-sentenced because some cases can go for decades, which means the families are also continually dealing with the emotional toll.

As for Gerald Pizzuto, the attorney general’s office said the case is scheduled to be argued before the Idaho supreme court in June.

Watch more Local News:

See the latest news from around the Treasure Valley and the Gem State in our YouTube playlist: