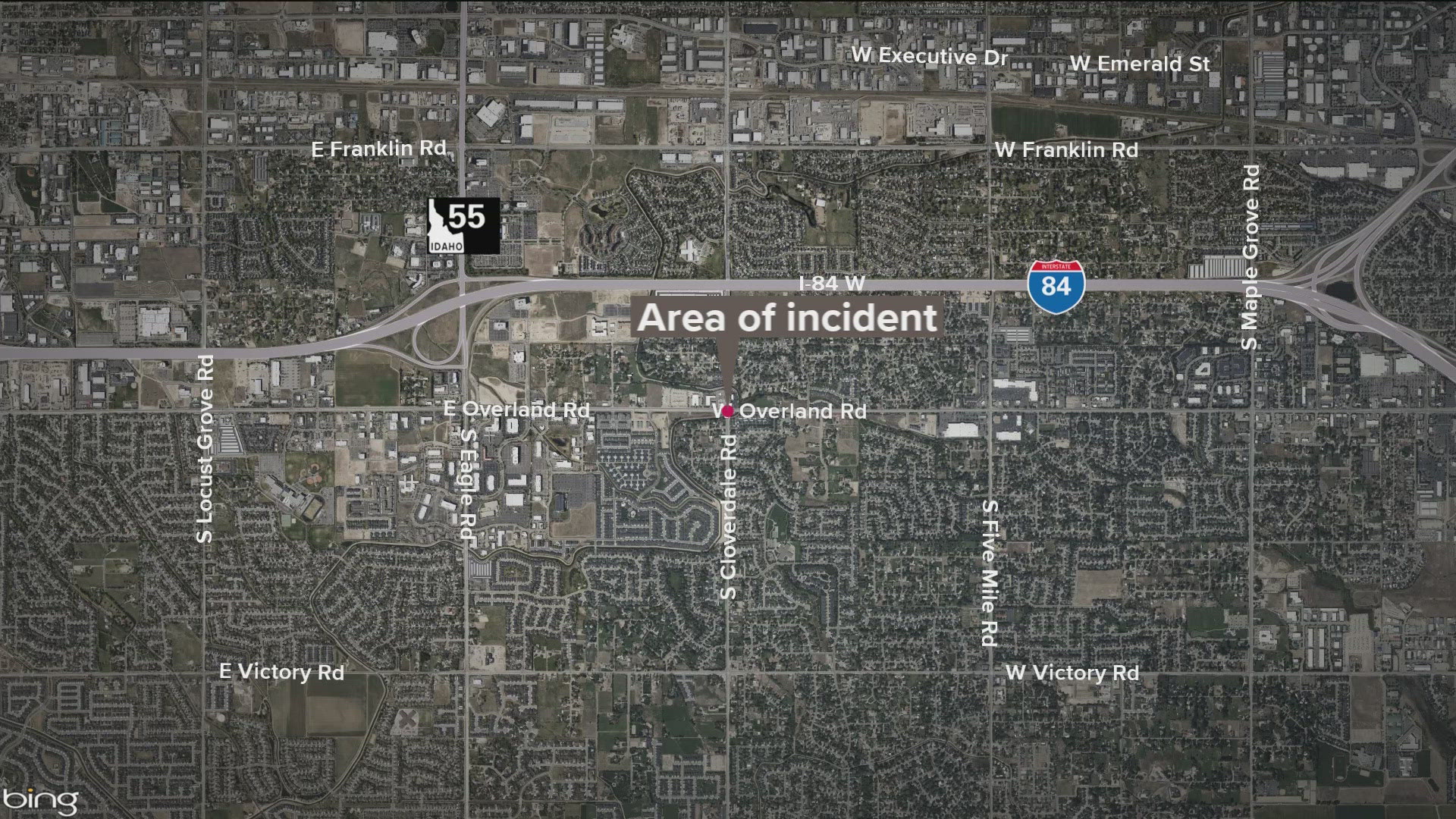

BOISE — Four-year-old Alliee Rose was buckled into her carseat in the back of the sedan when the fire started. It was 3:30 in the morning on April 10, in the parking lot of the Overland Road Walmart where her mother had stopped for the night.

Jennifer Miller was sleeping in the front seat, her baby son Lane on her chest. In the dark, a portable propane cooking device Miller had placed in the car to stave off the chill ignited.

Official reports indicate the flames woke Alliee up first. She called out to her mother - a fire!

As the flames reached her skin, Miller was able to escape the car with her 1-year-old, then tried to save Alliee.

She pulled at the back door, Judge Samuel Hoagland recounted, but it wouldn't open. She ran around to the other side, and opened that door.

In the darkness and the smoke, she reached for her daughter. As Miller struggled to unbuckle the girl's seatbelt, the propane tank exploded.

"At that point, it is believed, all was lost," Hoagland said.

Miller, 31, was sentenced Tuesday to 20 years in prison, with five years before she will be eligible for parole. She pleaded guilty in September to two felony counts of injury to a child.

Prosecutors argued the case is not summed up by the homeless mother's fatal decision to use a dangerous propane cookstove to keep her car warm.

Rather, Prosecutor Katelyn Farley argued, Miller had been failing her children for years.

Alliee was born addicted to heroin. Miller was clean when her younger child was born in 2016 - weeks after her graduation from Ada County's drug court - but relapsed into methamphetamine use within months.

"She could have been the mother her kids deserved at any point," Farley said. "She chose to use."

At the hospital where he and his mother were treated for burns after the car fire, Lane tested positive for both methamphetamine and heroin "at levels that could have killed him," Farley said. The boy is currently in foster care.

Girl dies in Boise car fire

Miller admitted to using methamphetamine four days before the fire, although Farley argued she was likely coming down from a high as she slept in the car - possibly contributing to why she did not awaken sooner.

Sleeping in the Walmart parking lot was not her only choice, the prosecution said. Miller could have taken her children to a relative's house, used money from pawning her possessions to rent a hotel room, or gone to a homeless shelter, Farley said.

"The defendant refused to accept that help," she said.

After years of second chances, the prosecutor argued, a lengthy prison sentence would force Miller to stay clean and take responsibility for what her drug addiction had wrought.

"Alliee doesn't get another chance," Farley said. "Lane does not get another chance to get his sister back."

But defense attorney Heidi Koonce argued that "warehousing" Miller in the prison system would serve no meaningful purpose. She urged Hoagland to place the defendant on probation to allow her to attend the intensive New Life addiction recovery program, run by City Light.

"Society is protected best when Jennifer is being rehabilitated," Koonce said. "This is her best chance at a successful future."

Miller struggles with PTSD and is haunted by her daughter's death, the lawyer argued, a prison sentence more severe than any that could be meted out in court.

"There is no punishment that parallels that type of sorrow, grief, and regret," Koonce said. "She made a horrible decision she can never take back."

But Hoagland handed down 20 years, the maximum sentence possible under state law. Miller will receive credit for the 200-plus days she has spent in the Ada County Jail.

In a brief statement, Miller told the judge the fire is never far from her mind.

"Every day, I replay that night over and over and over," she said. "It eats at me. I will forever carry that."

"I wish I could go back, but I can't," she continued. "I can't fix this one."