HORSESHOE BEND, Idaho — The stranger was armed with an AK-47, a handgun, and what he believed were divine instructions from God himself when he knocked on the door of the Horseshoe Bend mobile home where 11-year-old Micah Pecyna lived with his family on March 15, 2020.

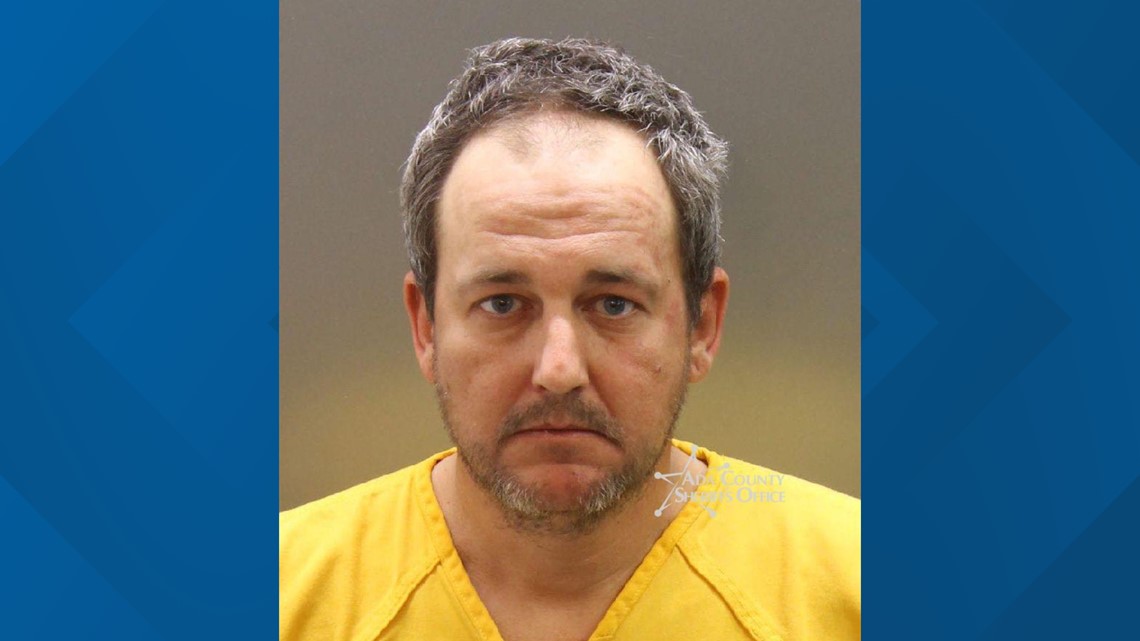

The man, 46-year-old Benjamin Poirier, had spotted the family at a nearby gas station and followed them home. When the door opened, Poirier first asked for help - then delivered an unsettling message.

"It's the end of the world," he said.

With the door to the home slammed shut again, Jolie French Pecyna dialed 911, telling a dispatcher the man was holding a rifle and told them that "he knew who they were."

"I have a child here," she told the dispatcher. "He's still knocking. We're in a trailer, there is nowhere to hide."

The knocking on the door stopped.

"Please hurry," Pecyna says on the 911 recording.

Then the only sounds on the line were the gunshots and the screaming.

Prosecutors say Poirier shot 40 rounds from the AK-47 into the trailer as he walked around it outside, then fired seven more shots from a handgun into the home.

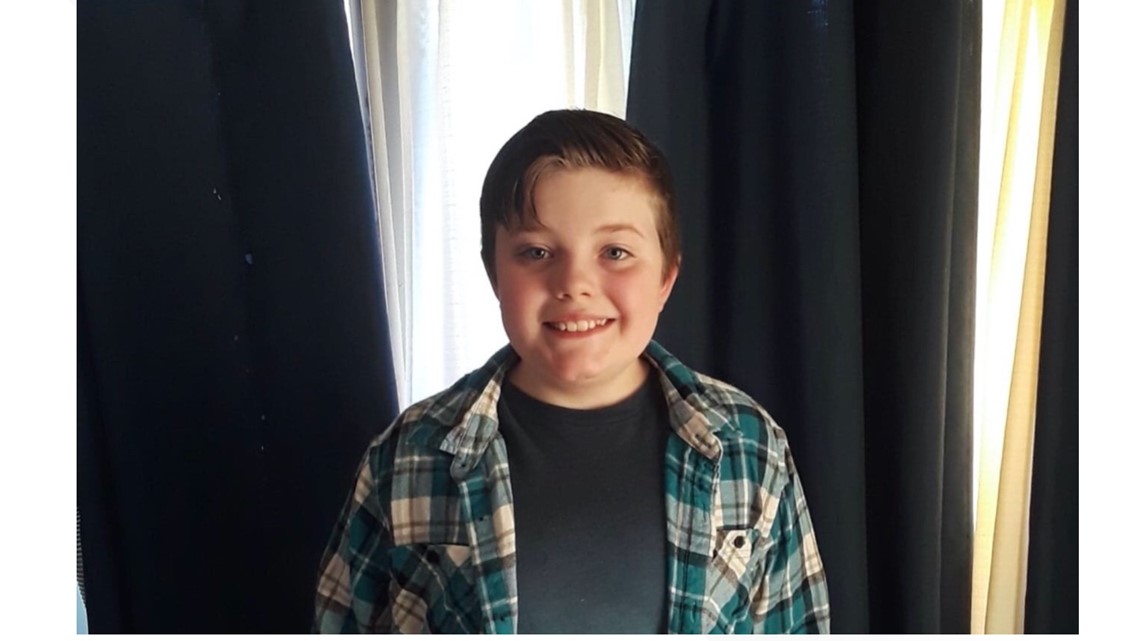

Micah, hiding inside with his mother and stepfather, was struck five times, Prosecutor Aaron Strong said. Bullets hit the fifth-grader in the ankle, calf, thigh, groin, and head, killing him.

"That's what Jolie has to go through the rest of her life," Strong said. "That's her last memory of her son."

Poirier was sentenced to life in prison without parole Friday afternoon, months after pleading guilty to Micah's murder in exchange for prosecutors taking the death penalty off the table.

Poirier's lawyers say he was in the grip of a psychotic break when the shooting happened, and had been hearing voices and interpreting sounds and music on the radio as commands. In court, Poirier told the judge he believed he had accidentally breathed in noxious chemicals that rendered him "temporarily insane," adding that he was horrified and filled with remorse at the knowledge that he had killed a little boy.

"I was hearing things, I was seeing things, I believed I was being told to do things by God," he said. "To me at the time, it seemed like I was supposed to be doing just that, that I was on a mission."

The violence sent shockwaves through Horseshoe Bend, where Micah often played with other children in the neighborhood.

Jolie Pecyna said that her son's classmates at Horseshoe Bend Elementary were struggling in the aftermath of his death, and that she has developed PTSD, panicking when she sees a car that seems to be following behind her own.

"A knock at the door is not just a knock at the door for my family and I anymore," she said.

Poirier ended the big plans of "a beautiful child", Pecyna said, a boy who wanted to build houses for homeless people, animal shelters for dogs, and was already talking about the day he would have children of his own.

"He loved his friends, he loved his family. He was kind, and he had so many dreams," she said. "Every day is another day I don't get to see my son accomplish those dreams."

The 11-year-old's sister, Kiana Braden, said everything is a reminder of the joys Micah will never get to experience again: Riding bikes with his friends, laughing at YouTube videos, fishing with his grandfather, baking cookies with his cousins.

Micah will never grow up, she told the judge, never go to college. He won't be there for her high school graduation. He won't be there for her wedding. If she has children someday, her brother will never meet them.

"Every little boy I see looks like my brother," she said. "Every family I see is a reminder that mine was destroyed."

Poirier's defense attorney, Elisa Massoth, asked the judge to allow him a chance at parole after 25 years in prison, noting that the defendant had only a minimal criminal history before the shooting.

"His actions that day were so completely out of the norm for him. He did not plan this crime," she said. "In that absolute detached from reality state he did something that was so completely out of character for him."

The defense also played video messages from some of Poirier's relatives, who described him as caring, gentle, and helpful.

"In his right mind, he would not harm anything or anybody," his mother Cynthia Anderson said. "He would not do violence to anybody."

But Strong, the prosecutor, argued that anything less than a fixed life sentence would be an "injustice."

After firing dozens of shots into the home, Poirier got back in his car and rammed it into the trailer's propane tank in an attempt to make it explode, Strong said.

"Have you ever seen someone so calm after killing a child?" he told law enforcement after his arrest.

The prosecutor said that Poirier was still more concerned with himself than what he had stolen from the people who loved Micah.

"He extinguished this family's hopes," Strong said.

Judge Samuel Hoagland handed down the fixed life sentence requested by the prosecution, telling Poirier that he could not be sure he would not still be a threat to society even if released in old age. The killing was "random, senseless and tragic," Hoagland said, expressing his condolences to the boy's family.

Poirier had waived his right to appeal as part of the plea deal. He was also ordered to have no contact with the victim's family while in prison.

The life sentence drew exclamations of relief from the gallery, as some watching embraced or raised their hands in a gesture of victory.

Still, Micah's grandmother Kathy French told the judge before the sentence was pronounced, no action in court would give the family relief from their heartache.

"Justice would be Micah here with us," she said.

Watch more crime news:

See the latest Treasure Valley crime news in our YouTube playlist: