BOISE, Idaho — Crisis standards of care were expanded Thursday by the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare to the entire state, as COVID-19 infections continue to outpace medical providers' ability to care for all the sick.

The activation came after a request by St. Luke's Health System.

Crisis standards of care on September 7 were activated for the first time in Idaho, for the Panhandle and North Central health districts, and other districts in the state were expect to follow as hospitals address the recent surge in new COVID-19 cases.

Also in early September, for the second time in the 18 months since the pandemic hit Idaho, Gov. Brad Little called on the Idaho National Guard to assist hospitals and clinics around the state in what he called a "last-ditch" effort to keep providers from having to go to crisis standards.

The Idaho Board of Health and Welfare adopted a temporary rule in December, nine months after Idaho's first COVID-19 case. The rule allows hospitals to move into crisis standards of care if things get to the point where they don't have enough resources to provide the standard level of care for every patient who needs it.

Those resource issues may be related to equipment or treatments, they may be related to staffing levels, or they may be related to all of the above.

Under the rule, hospitals could move into crisis standards without seeking approval from the governor.

A plan adopted by the Idaho Dept. of Health and Welfare is intended to help providers "achieve the best healthcare delivery outcomes" during any emergency or disaster in which the health care system may be overwhelmed, including the current COVID-19 pandemic.

It's not about planning to have a crisis, but rather having a plan to keep the health care and emergency response systems working as well as possible in the event of a crisis.

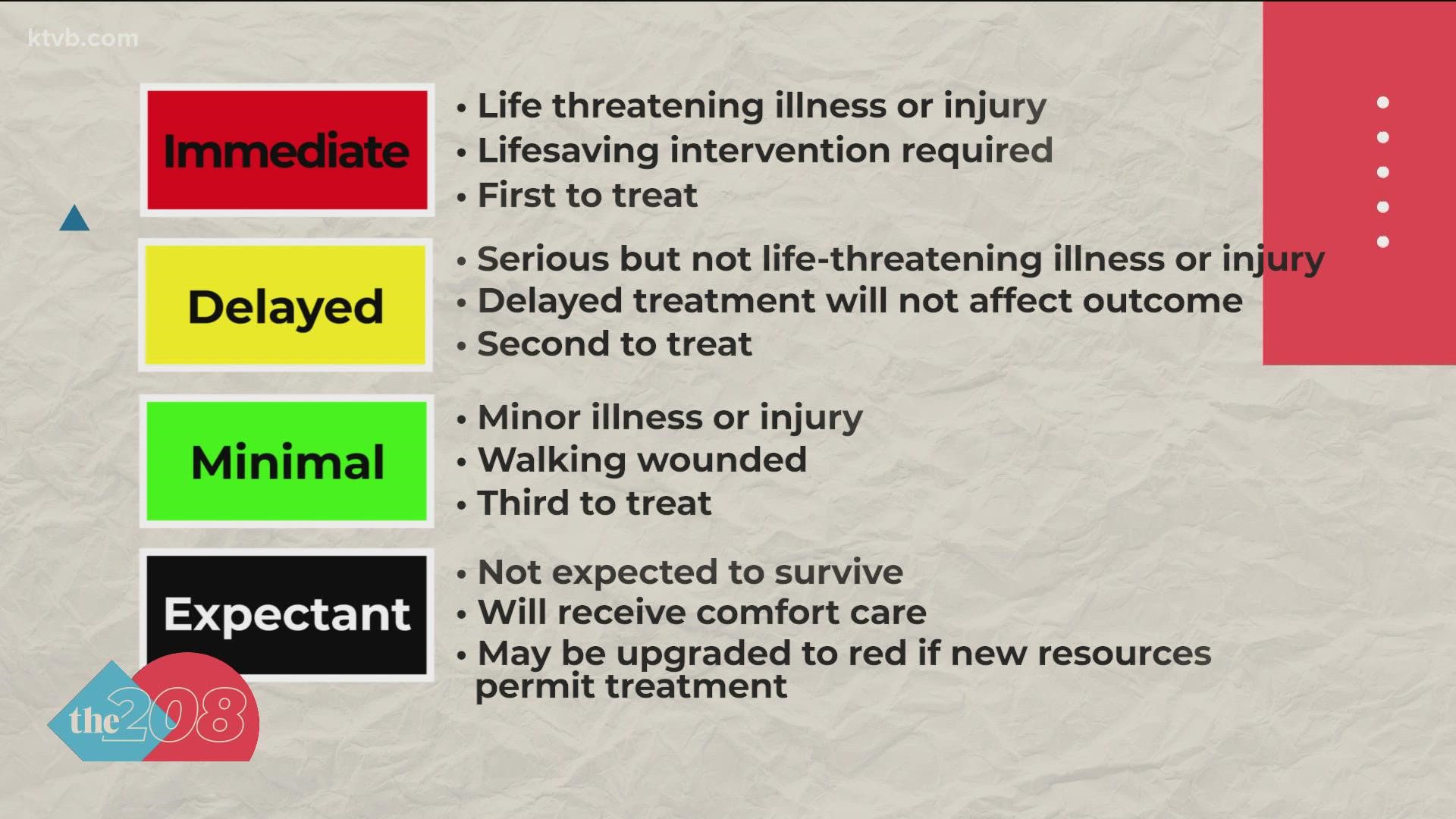

To boil a 48-page document down to one sentence, it's possible that non-urgent or less-urgent care may not be provided in order to ensure timely response to the most severe life-or-death emergencies. That concern extends to 911 calls for emergency medical service.

The term "crisis standards" refers to the most extreme operating conditions along what's called the continuum of care -- which ranges from "conventional" to "contingency" to "crisis."

Think of conventional care as the level of service you've come to expect when things are going relatively well -- the usual staff are called in, hospital spaces are available for their intended purposes, and recommended treatments are available.

In crisis conditions, supplies -- including some life-sustaining resources -- are lacking. In the most extreme shortages, resources may be allocated to patients with cases more likely to have a positive outcome.

A shortage of ventilators, for example, may mean that someone less likely to survive because of underlying conditions would not be put on a ventilator if someone with a more positive prognosis also needed one. However, that is not necessarily what will happen under crisis standards; it is mentioned in the IDHW plan as a general approach to consider when developing specific guidance.

Another strategy short of prioritizing who will receive limited resources is conservation. For example, lowering dosages of medication or, regarding some supplies, disinfecting or sterilizing them, then reusing them.

Idaho Health and Welfare Director Dave Jeppesen has called crisis standards "a very last resort."

Between conventional care and crisis care is contingency care.

In contingency care, an equivalent treatment - or at least the best available - could be substituted for what would otherwise be available.

Also, patient care areas may be repurposed. An indicator of a more severe crisis would be when non-patient care areas -- even a facility that's damaged or considered unsafe -- may be used for patients.

A healthcare facility would be in a staffing crisis if trained staff were unavailable or unable to adequately care for all patients even when extension techniques, such as postponement of non-urgent care or a change in staff responsibilities, are used.

The transition from conventional to contingency standards may occur at the local or regional level when local jurisdictions are requesting resources, when the availability of treatments or vaccines is declining, when one or more hospitals has to divert patients, or when the ability to transfer patients across all or part of the state is limited.

For the Idaho Crisis Standards of Care Plan to be activated, some or all of the following must be true:

- State and federal disaster declarations are in place or have been requested

- Most or all of the state's healthcare infrastructure has been impacted

- Available resources are insufficient to provide the usual standard of care

- Multiple healthcare organizations within a community or region are similarly affected

- Patient transfer or transport to other facilities is not possible or feasible, at least in the short term

- Medical countermeasures such as vaccines, medications, antidotes or blood products are depleted or otherwise unavailable

- Trained health care staff is not available or not able to adequately care for the volume of patients needing care

- Federal, state, regional or tribal stockpiles of equipment, supplies or pharmaceuticals have already been distributed, and no short-term resupply is expected

- There are disruptions to the healthcare supply chain

The IDHW plan states that the precise trigger point for transitioning from contingency to crisis at the state level will be determined by the IDHW director in consultation with the Governor’s Office, IDHW Operations Center, the state's disaster medical advisory committee - "SIDMAC," the Idaho Office of Emergency Management, local health officials, and healthcare system stakeholders.

Facts not fear: More on coronavirus

See our latest updates in our YouTube playlist: