BOISE, Idaho — On the day Steve Bair’s father died in 2017 in eastern Idaho, “He had been quite ill, and we took him to the hospital in Idaho Falls,” Bair recalled.

“The doctor came in and said, ‘Does he have an advance health care directive?’ I said, ‘He sure does.’”

The Idaho Press reports Bair, a state senator and co-chairman of the Legislature’s joint budget committee, knew his dad had registered his advance care directive with a registry maintained at the Idaho Secretary of State’s office, something the state created in 2005. It’s the official place where health care directives, also known as living wills and durable power of attorney, can be filed, under state law, to allow people to express their wishes about their own end-of-life care. That could include when or if a patient wants artificial life support, tube feeding, a ventilator or other measures as they approach death.

But there was a problem. The doctor asked Bair, “Can I see it?” Bair responded that it was in Mackay, but it was registered with the state — so he assumed the doctor could look it up online.

However, there was no way to do that. All of the nearly 42,000 health care directives that have been filed with the state office since 2005 are still there, but they’re not online. And there’s no way for any health care provider to get access to them.

“The only person that has access to it was the person that put it in there,” Bair learned. “It’s ridiculous.”

Idaho Secretary of State Lawerence Denney told the Idaho Press that his office probably wasn’t the right place for the registry.

“Basically what happens is they send in their application to us, we send ‘em out a card, the card goes on their refrigerator at home, and when they’re in the hospital they don’t have anything,” Denney said.

“We don’t have any expertise in medical” matters, he said. “We were kind of the recording place, but I don’t think it was doing anything to help people.”

The registry started small, but has grown dramatically. It had 25,000 filings in 2016; it’s nearly doubled since then. A full-time employee in the Secretary of State’s office processes the filings on paper and enters them manually.

Bair took his concerns to the Idaho Hospital Association, and learned that a group of stakeholders was working to come up with a better system.

“This will not only save millions, this will save heartache,” said Brian Whitlock, IHA president. “It’s entirely consistent with the governor’s directive on let’s find ways to control costs.”

Extraordinary measures to keep a person alive when they’re terminally ill can be very expensive; when the patient can’t communicate to share his or her wishes, they can also be unwanted.

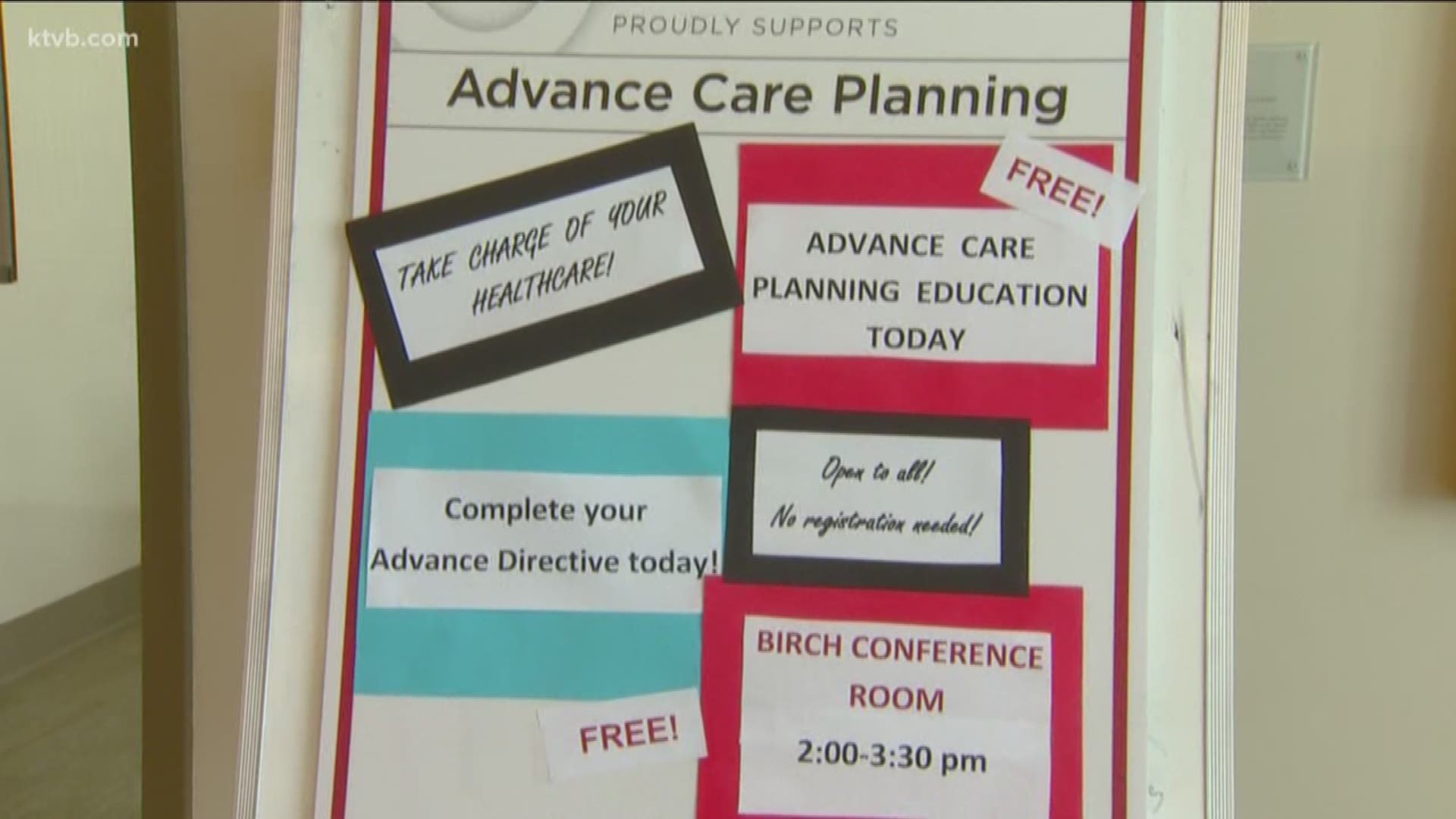

The IHA and the two large hospital systems in Boise, St. Alphonsus and St. Luke’s, had come together with the state’s four largest insurers to start a pilot program for an accessible registry of advance care directives, funding it themselves and obtaining grants, and launching a marketing campaign. The “Honoring Choices Idaho” program turned out to be a successful pilot program, Whitlock said, prompting all those involved to look at how it could be expanded statewide.

Now, three years later, Gov. Brad Little is proposing a new health care directive registry at the state Department of Health and Welfare, where the documents would be secure under medical privacy laws, and also readily available online to caregivers across the state.

Little’s budget proposal for next year includes $500,000 from the state general fund to develop the new registry program. That would include one-time technology and implementation costs for a cloud-based system, and ongoing maintenance, education and technical assistance in future years; the registry would expand statewide over the next three years. There may also be policy legislation this year to change the registry over to Health and Welfare.

When the Department of Health and Welfare had its budget hearing last week for its Public Health Services division, the new advance care directive registry was front and center, and lawmakers on the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee were receptive.

Whitlock said, “It makes sense, and it’s worked really well in other states.”

Bair said having the registry at the Secretary of State’s office ran into issues with medical privacy. “We had to locate it in a place that had the proper level of security,” he said, and experience with the federal HIPAA law, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, which governs privacy of medical records.

“I think we’re on track to have doctors and end-of-life caregivers be able to access that information,” Bair said. “It’s going to cost some money. It’ll be a new database.”

Bair said when he asked Little’s budget director, Alex Adams, about the prospect, “He said, ‘That’s a no-brainer,’” Bair said. “I’m just tickled to death.”

“I think we’re going to get it done,” said Bair, R-Blackfoot. “I’d be honored to carry it on the floor if I’m asked to do that.”

More from our partner Idaho Press: 'Reiterating safety precautions': Local 1st responders prepare for possible coronavirus threat

Watch more 'Idaho Politics'

See them all in our YouTube playlist here: