BOISE, Idaho — An innovative approach to criminal investigations first came to the forefront around 2018. Since then, forensic investigative genetic genealogy, or FIGG, has been instrumental in cracking hundreds of cold cases and ongoing investigations.

Court documents show it was used to connect Bryan Kohberger to the University of Idaho murders in Nov. 2022. Prosecutors say law enforcement used FIGG to link Kohberger to DNA found on a knife sheath left at the home where four students were killed.

Law enforcement in Idaho said FIGG is a key piece of the puzzle in bringing closure to victims and families living with unsolved cases, including the Casper family.

In 1987, 65-year-old Joyce Casper was abducted outside her Hallmark store at the Vista Village Shopping Center, sexually assaulted, strangled and killed. One of her daughters, Pauline Casper, said Joyce worked very long hours late into the night and she was abducted after leaving work. Police found her body inside her car two blocks down the road from her store near railroad tracks.

“I was definitely stunned,” one of her daughters Roberta Casper Watson told KTVB.

“You just kind of go blank and you have a ton of questions all at the same time,” Pauline added.

Casper’s murder case went cold – until 2023. Boise police finally answered the decades-old question of who killed her.

Boise Police Department (BPD) Det. Paul Jagosh says FIGG cracked this case. Using the suspect's DNA preserved from the crime scene decades ago, a lab created a genetic profile of the suspect and uploaded it into a genetic genealogy database.

“We had a profile of a [half first cousin] once removed, someone that's clear across on the other side of the family tree and we didn't have anything in between,” Det. Jagosh said.

BPD hired a forensic genealogist to build a family tree using open data and public records. Investigators tracked down and contacted family members, ultimately finding the suspect's two sons.

“They consented and then both matched. And that was through a private company. And then we used ISP to basically confirm through law enforcement,” Jagosh added.

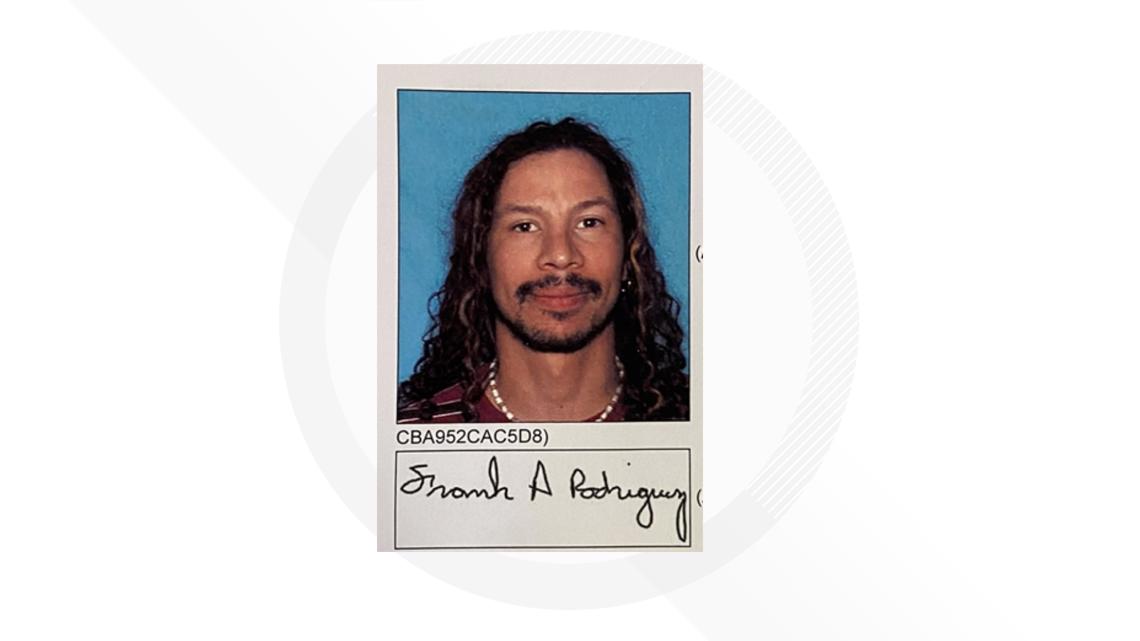

Police were able to determine the suspect was a man named Frank Rodriguez. There is no known connection between Casper and Rodriguez. Rodriguez took his own life several years after the murder and before law enforcement named him as a suspect.

“You go 35 years and you just assume that you will never know. And it's this thing that you carry inside of you. It's always there. It never leaves. It's just a fact of your life that, you know, this horrific murder and assault occurred to your mother,” Pauline told 7 Investigates.

As required by Department of Justice policy, law enforcement must first run DNA through the FBI’s national database, Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). If there's not a match, they can resort to FIGG - DNA analysis combined with genealogy research - to generate investigative leads.

Matthew Gamette, Idaho State Police Forensic Services Laboratory System Director, said FIGG covers two topics: investigative genetic genealogy (IGG) and forensic genetic genealogy (FGG).

FGG covers DNA sequencing done in labs – mostly private labs currently -- to build genetic profiles; on the investigative side, those DNA profiles are uploaded into certain publicly-available DNA databases or genealogy services and compared with people who submitted their profiles and gave permission for law enforcement to use them.

“It could be anything from taking the genetic information and putting it into a database and then building out genealogical trees - family trees - to be able to work with that information,” Gamette said.

He said this technology has changed the game for investigations.

“If it’s in the United States and family lines are here we are generally doing a pretty good job of making those connections and doing it pretty rapidly,” Gamette added.

Through grants, the federal government gave ISP’s Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI) team $5.2 million over the past several years. The money is used to solve cold cases, improve DNA collecting and testing, and identify sexual and other offenders. In this year's budget, Idaho Gov. Brad Little gave the team another $50,000.

Gamette credited the SAKI team with solving four cold cases that they’re able to publicly announce at this time.

“However there are other cases that are active right now that we believe we have the suspect and are working on that with local agencies to write warrants to get DNA. Or there are cases in grand jury… so we can’t announce yet because they’re not adjudicated at this point. But there are lots of cases in Idaho that are very active with this technology and this technique,” Gamette told 7 Investigates.

Det. Jagosh is working on one other decades-old Boise cold case that he hopes to solve using forensic investigative genetic genealogy.

Jason Cannon was almost three years old when he went missing from the front porch of his family's West End apartment in March of 1983.

After law enforcement scoured the canal behind the little boy’s apartment, they determined Jason was likely abducted.

Investigators have Jason's parents' DNA, but not Jason’s. If they find his remains, they could compare the DNA. But if he is alive, Jagosh says the possibility of using FIGG to help solve the case is high.

“At this point in the case - other than a few leads we're trying to run down - it's basically a waiting game of either him, or if he has children, of doing some type of family tree, some kind of genetic testing,” Jagosh said. “We're hopeful. We're really hopeful for the family.”

“When the mom asked me: ‘are you gonna find my boy?’ it just broke my heart… I’ve got to keep working, got to keep working, and that's when I put his picture on my desk so I don't forget,” Jagosh added.

When she first learned BPD solved her mother’s case, Roberta said she didn’t feel any semblance of closure – but that’s since changed.

“Over time I think it has because I feel less unsettled about it now. And for a long time I kind of felt unsettled about it… I put a lot of energy into trying to accept that we just would never know and that there was nothing we could do about it. And, you know, life must go on,” Roberta said. “A story must have an ending. And so the story now has an ending.”

Pauline said seeing the suspect’s driver’s license photo made a huge difference for her.

“I didn't have to carry around some monstrous picture in my mind anymore. It's like, oh that's what he looks like, that's the one who did it. So, yeah, it did bring closure for me,” she said.

Roberta and Pauline are hopeful more cases will be solved using this technology.

“There are so many people who are living with an unsolved case in their lives,” Pauline told 7 Investigates, “I just want to be able to give hope to people to know that the more updated the technology and the, you know, the genealogy investigations that they're doing now is amazing. So don't ever give up.”

Jagosh and Gamette noted DNA isn't found in every crime so not every cold case can lean on this technology.

BPD said detectives have opened other cold cases with DNA evidence and Det. Jagosh believes FIGG is being used on some of those. However, the department can't give KTVB any more information because they are active, open cases.

When FIGG first came to the forefront, Gamette says it was the “wild west” -- the technology was robust but policies and procedures didn't exist. In the last few years he said ISP has helped lead the country in coming up with policies around using and securing databases and addressing ethical and privacy concerns.