People that you should know for Black History Month 2023

February is Black History Month, and every day, we will showcase a prominent figure in Black history.

February is Black History Month. Every day, we will showcase a prominent figure in Black history.

FEBRUARY 1-5

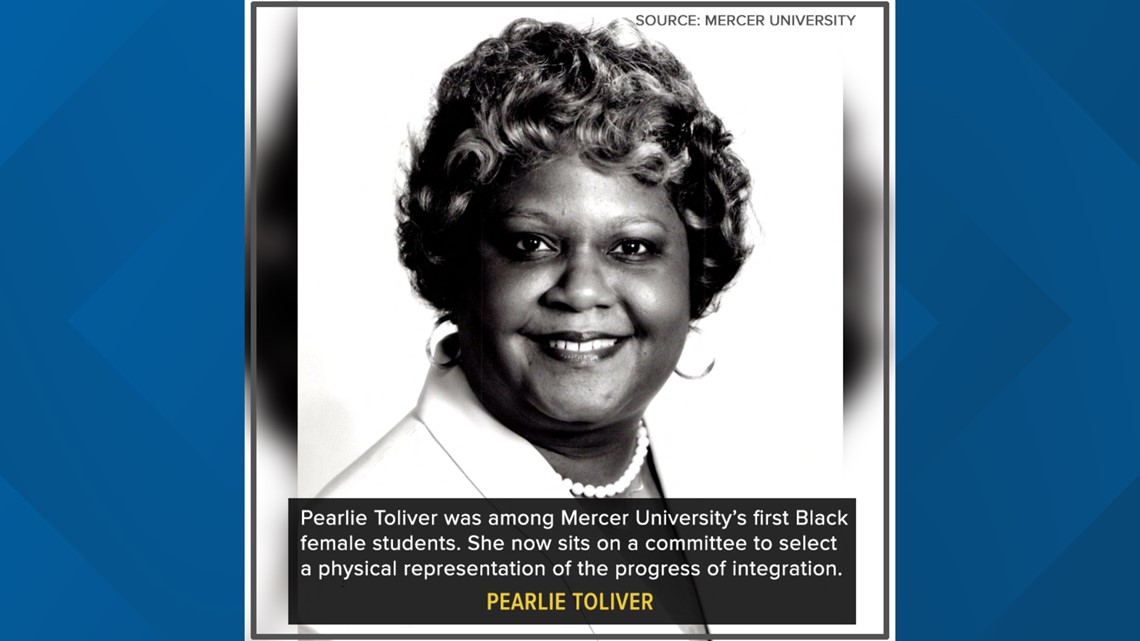

PEARLIE TOLIVER

Alumna Pearlie Toliver was among Mercer University’s first Black female students.

60 years ago, Toliver served on an ad hoc committee to plan the University’s celebration of 50 years of integration. She now sits on a committee to select a physical representation of the progress and ongoing mission of integration.

After graduating from Mercer, Toliver went on to have a successful career in retail banking and mortgage lending, retiring after 37 years as vice president from Branch Banking and Trust Co. She previously served as the community reinvestment officer/lender for the bank for 12 years.

In 1985, Toliver graduated from Leadership Macon, a yearlong program that introduces a class of upcoming community leaders to the qualities and challenges of Macon-Bibb County. In 2017, she received the Robert F. Hatcher Distinguished Leadership Award for her service in the program. In addition, she is a recipient of the Women of Achievement Award in Macon and the Liberty Bell Award from the Macon Bar Association.

Toliver currently serves as chair for the Board of Commissioners of the Macon Housing Authority. She previously served as a member of the Bibb County Consolidated Government Transition Team where she was chair of the Finance Committee.

She has also served on various boards and commissions in Macon and the state of Georgia, such as the 1999 Macon-Bibb Unification Commission, the Georgia Tobacco Commission and the Georgia Student Finance Commission. Representing Mercer, she participated in the Achieving the Promise of Authentic Community-Higher Education Summit.

Toliver is a lifetime member of the Greater Macon Chamber of Commerce and has participated in the local and state boards for the League of Women Voters. In her spare time, she enjoys music and helping others achieve economic success and financial security. She is married to her husband, John Toliver.

(INFO: MERCER UNIVERSITY)

--------------

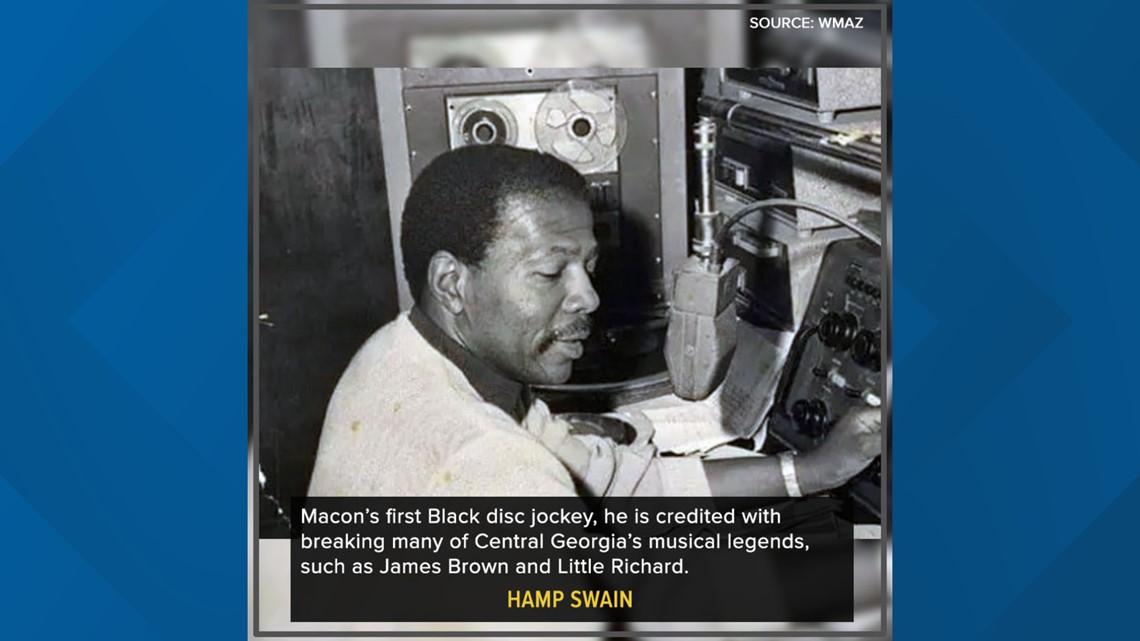

HAMP SWAIN

The legendary Hamp Swain was Macon’s first African American disc jockey. He started at radio station WMBL in 1954, later moving to WIBB AM 1280.

His place in time made him a historic factor in the fame of artists like the “Godfather of Soul” James Brown, Otis Redding, and the founder of Rock and Roll, Little Richard.

Hamp Swain gained the nickname “King Bee” after singer Slim Harpo’s song, “I’m a King Bee.”

Music was in Swain’s soul long before he hit the airwaves as a disc jockey. He attended college for a short time and later went to work as an insurance agent for Atlanta Life, but it was his enjoyment of playing the saxophone that led him to start his own band called the Hamptones. He would occasionally feature his high school friend Little Richard Penniman on vocals.

The Hamptones performed around the country. Noted are some specific concerts like the one at Los Angeles Wrigley Field in July 10, 1949, and the show at San Diego’s Lane Field in September 3, 1949.

Hamp Swain will be remembered for opening the doors for many of Central Georgia’s musical legends. Among the biggest names include James Brown. In 1956, “King Bee” played “Please, Please, Please” on the radio.

Hamp Swain hosted the well-known “Teenage Parties,” a talent competition most often won by local singer Otis Redding.

Swain started his own recording label in Macon in the late 1960s. The company, Var-Val, was named after his children, Jarvis and Valencia.

Swain is quoted as saying, “Why Macon? I used to say it was the water, something in the water.” "Something in the Water" incidentally became the title of a book about Macon’s music history by Ben Wynne.

Swain is credited as being the guiding force behind the R&B scene in Macon and was inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of fame in 2008.

Swain died at age 88 of natural causes in 2018. Charles Davis with 100.9 The Creek in Macon said, “The world lost a great man.”

“Hamp is gone,” Little Richard Penniman, who died in May 2020, two years after his high school friend, told the Telegraph on the phone from his Nashville, Tennessee home. “Old Hamp Swain, my buddy. He gave me my first job as a vocalist.”

(INFO: 13WMAZ)

----------

NATHAN BLACK

Unknown to many people is just how musically-rich Macon’s Pleasant Hill community has been during its earliest years to now.

Among the eclectic styles of musicians lived and teaching in Macon was Professor Nathan Black. Black was known as one of the greatest piano players in this area.

He shared that skill with countless students around Macon. There is no way to know just how may benefited from his door-to-door lessons. Not only was he an extraordinary pianist, but a skilled violinist. He taught anyone who wanted to learn how to play either or both instruments.

According to a Macon Magazine June/July 2022 article, Craig Wright remembers the man he calls an “icon, music mogul” of Pleasant Hill. As a gifted base player, Craig Wright was a product of the rich musical training flowing through the Pleasant Hill community.

Wright describes Nathan Black, “He was a virtuoso that went around with a briefcase full of music.” Wright says his oldest sister was one of Black’s students, and that gave him many opportunities to talk with him. Along with his excellent music skills, Wright says Professor Black was a well-spoken gentleman using “impeccable correct English, all the time.”

“He looked like Mozart, with his gray hair combed to the back, always wearing Black, a little short guy, very neat with a deep, regal voice,” described Wright.

From one legend to another, the late broadcaster and musician Hamp Swain said of Professor Nathan Black, “I knew him to be one of the greatest pianists in this area. he was quite talented.”

Black died many years ago, but the spirit of his shared talent lives on as a foundation in Pleasant Hill’s musical history.

(INFO: WMAZ)

----------

ROMAY DAVIS

Millions of letters and packages sent to U.S. troops had accumulated in warehouses in Europe by the time Allied troops were pushing toward the heart of Hitler’s Germany near the end of World War II. This wasn’t junk mail — it was the main link between home and the front in a time long before video chats, texting or even routine long-distance phone calls.

The job of clearing out the massive backlog in a military that was still segregated by race fell upon the largest all-Black, all-female group to serve in the war, the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. On Tuesday, the oldest living member of the unit is being honored.

Romay Davis, 102, was recognized for her service at an event at Montgomery City Hall. It follows President Joe Biden's decision in March to sign a bill authorizing the Congressional Gold Medal for the unit, nicknamed the “Six Triple Eight.”

Davis, in an interview at her home, said the unit was due the recognition, and she's glad to participate on behalf of other members who've already passed away.

“I think it's an exciting event, and it's something for families to remember,” Davis said. “It isn't mine, just mine. No. It's everybody's.”

The medals themselves won't be ready for months, but leaders decided to go ahead with events for Davis and five other surviving members of the 6888th given their advanced age.

Following her five brothers, Davis enlisted in the Army in 1943. After the war the Virginia native married, had a 30-year career in the fashion industry in New York and retired to Alabama. She earned a martial arts black belt while in her late 70s and rejoined the workforce to work at a grocery store in Montgomery for more than two decades until she was 101.

While smaller groups of African American nurses served in Africa, Australia and England, none matched the size or might of the 6888th, according to a unit history compiled by the Pentagon.

Davis' unit was part of the Women's Army Corps created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1943. With racial separation the practice of the time, the corps added African American units the following year at the urging of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and civil rights leader Mary McLeod Bethune, according to the unit history.

More than 800 Black women formed the 6888th, which began sailing for England in February 1945. Once there, they were confronted not only by mountains of undelivered mail but by racism and sexism. They were denied entry into an American Red Cross club and hotels, according to the history, and a senior officer was threatened with being being replaced by a white first lieutenant when some unit members missed an inspection.

“Over my dead body, Sir,” replied the unit commander, Maj. Charity Adams. She wasn't replaced.

Working under the motto of “No Mail, Low Morale,” the women served 24/7 in shifts and developed a new tracking system that processed about 65,000 items each shift, allowing them to clear a six-month backlog of mail in just three months.

“We all had to be broken in, so to speak, to do what had to be done,” said Davis, who mainly worked as a motor pool driver. “The mail situation was in such horrid shape they didn’t think the girls could do it. But they proved a point.”

A month after the end of the war in Europe, in June 1945, the group sailed to France to begin working on additional piles of mail there. Receiving better treatment from the liberated French than they would have under racist Jim Crow regimes at home, members were feted during a victory parade in Rouen and invited into private homes for dinner, said Davis.

“I didn't find any Europeans against us. They were glad to have us,” she said.

The 6888th previously was honored with a monument that was dedicated in 2018 at Buffalo Soldier Military Park at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. But immediately after the war, members returned home to a U.S. society that was still years away from the start of the modern civil rights movement with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955.

(INFO: WTHR)

---------------

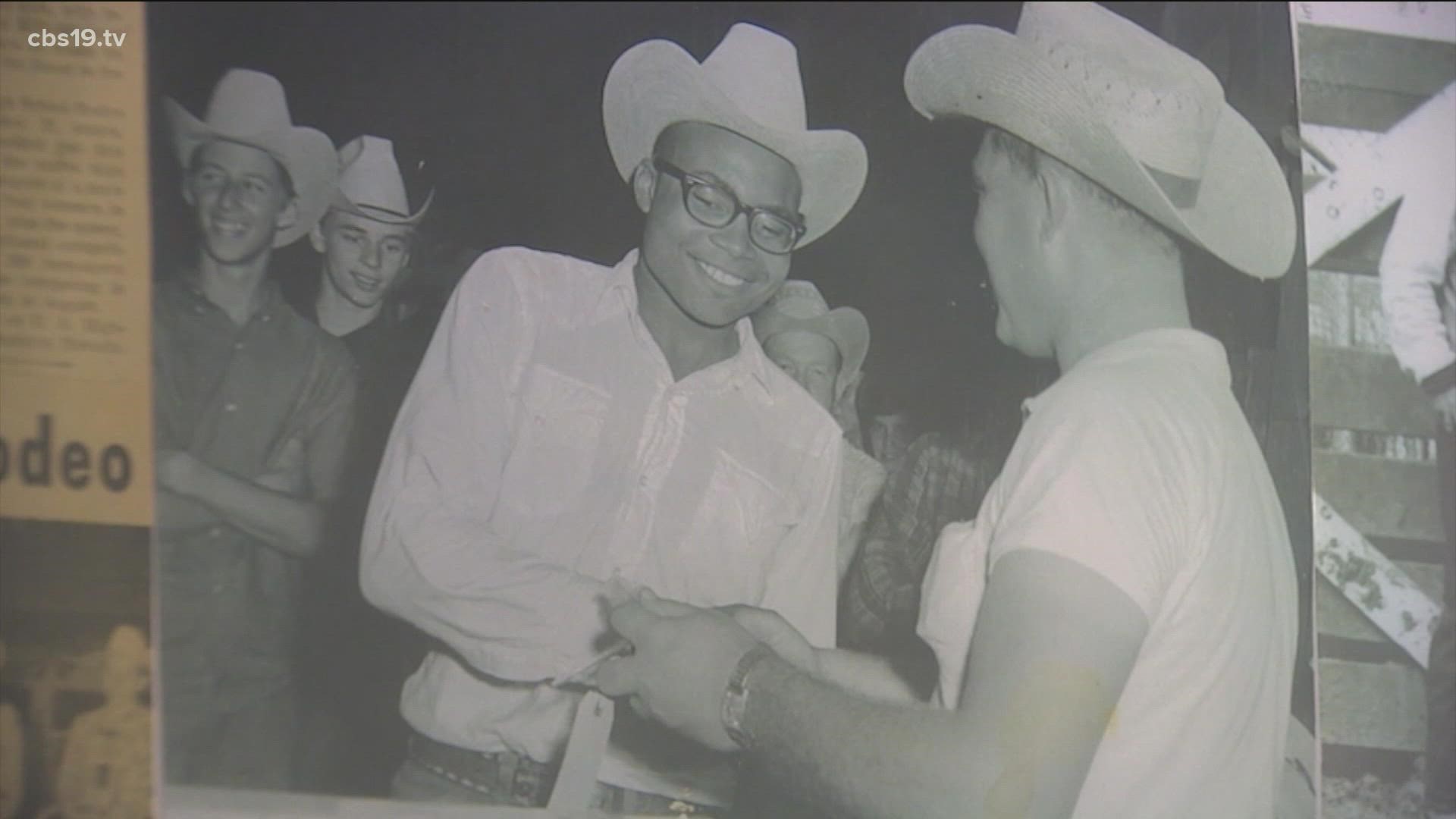

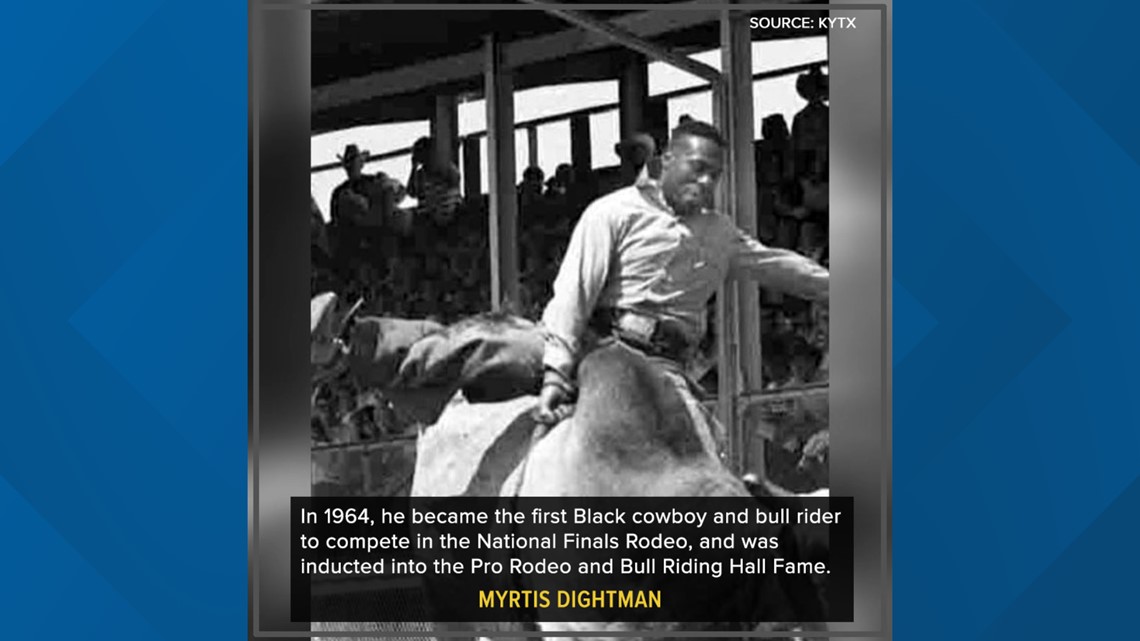

MYRTIS DIGHTMAN

Before cowboys like Myrtis Dightman, names like Bill Pickett and Nat Love were known to be the first of a few African-American cowboys that ruled the Wild West during the 1800 and 1900s.

During those times, African Americans weren’t given the opportunity to compete in rodeos due to segregation and discrimination.

Dightman changed that by becoming the first Black cowboy and bull rider to compete in the National Finals Rodeo in 1964.

“He's known now as the Jackie Robinson the rodeos," said Myrtis Dightman Jr. “When you make history there now the challenge and the challenge was to keep going to be the best cowboy.”

Dightman proved to be one of the best cowboys, he qualified for the National Finals Rodeo six times during the 1960s and '70s to become top-ranked in professional bull riding.

Dightman’s determination and eagerness to complete and win broke racial barriers surrounding Black cowboys and rodeos.

Today, at 86 years old, Dightman, along with his children and grandchildren, help to train the next generation of cowboys and cowgirls of all races to compete in state and national competitions, right in his hometown of Crockett...where it all started.

“Just to keep rodeo alive, back in those days they did not have that but now, their kids are 9 years old to 18 years old competing to become a world champion,” said Dightman Jr.

In 2011, Dightman was inducted into the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame. In 2016, he was inducted into the Pro Rodeo and Bull Riding Hall Fame.

(INFO: KYTX)

FEBRUARY 6-12

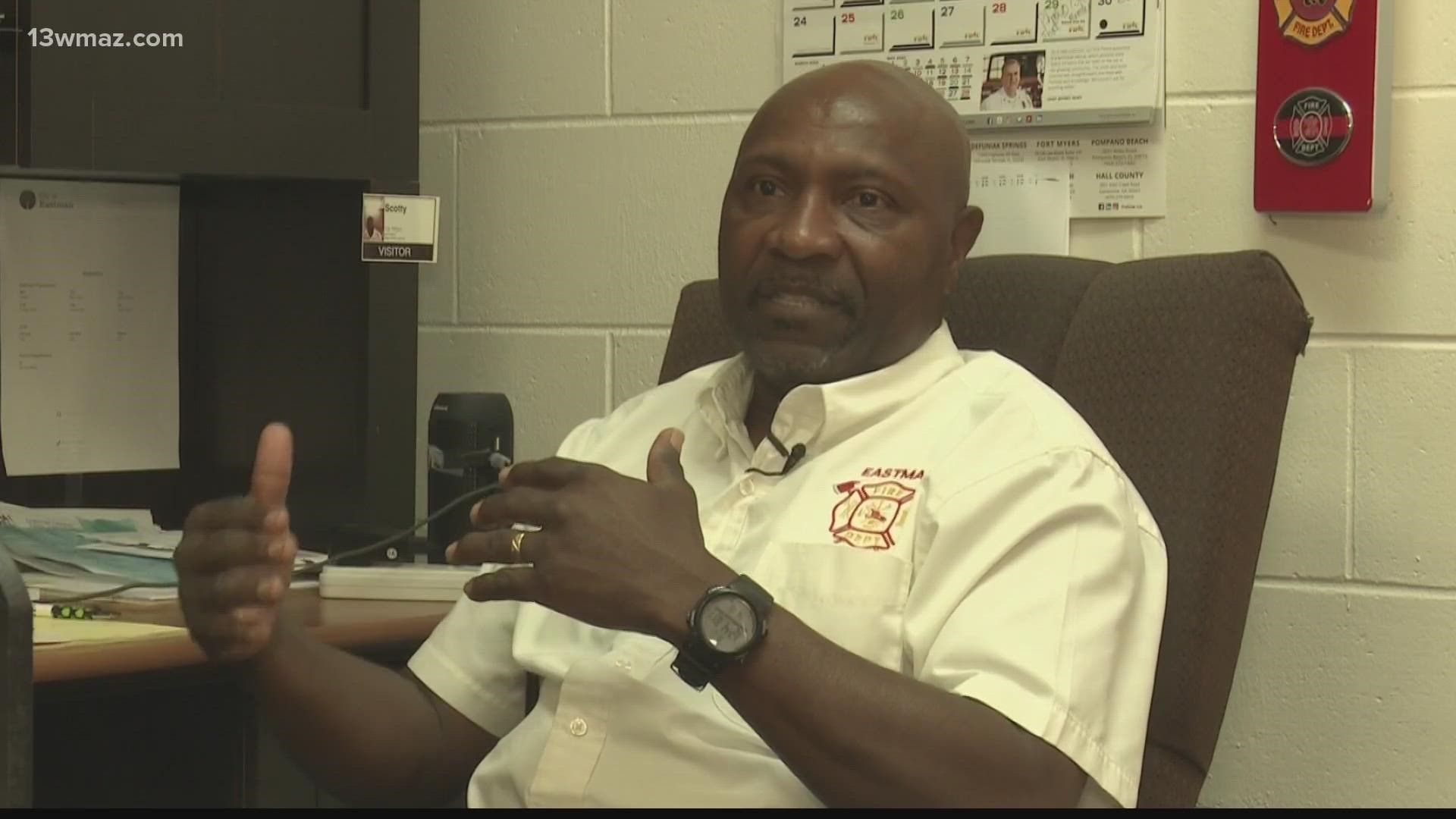

SCOTTY WHITTEN

The City of Eastman made history with its fire department in several ways.

Scotty Whitten is Eastman's first Black fire chief.

He started as a firefighter at the station in 2000 before becoming assistant chief four years ago. He accepted his new role on April 26, 2020, and history was made.

Chief Whitten says he couldn't do it alone.

"Everything we do here is a team. It's a team and that's what makes it so easy... I trust these guys because I see them when no one else sees them. They're training and perfecting their craft here at the department," said Whitten.

Since his hiring as head chief, Whitten has hired the first female firefighter at the station, Hannah McCranie, and the first Hispanic firefighter, Daniel Gonzalez.

(INFO: WMAZ)

--------

LUCY CRAFT LANEY

Born in Macon on April 13, 1854, Lucy Craft Laney's destiny was educational greatness. She used the freedoms she received to become one of Georgia’s greatest educators, a school founder, and civil rights activist. Laney’s impact on education lives on today.

Unlike today, freedom was not a given in the mid-1850s. Laney was born free because her parents were able to obtain freedom. Her father, David Laney, was a Presbyterian minister and skilled carpenter. He was able to purchase his freedom about 20 years before Lucy was born. He purchased his wife Louisa’s freedom soon after their marriage.

Laney’s father was a pastor at Washington Avenue Presbyterian Church at in Macon. Her mother worked at the Hay House on Georgia Avenue. It was there that a lady named Mrs. Flora started to pay special attention to Laney’s education. It was uncommon of Black people of that day to know how to read, but by the time Laney was 4 years old, she had learned how to read and write. By the time she was 12, she was able to translate difficult passages in Latin, including Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War.

Laney attended Lewis High School in Macon, which was later renamed Ballard High School. In 1869, she joined Atlanta University’s very first class. After graduating from the teacher training program, Laney went on to teach for 10 years in four Georgia cities.

Lucy Laney touched students across Central Georgia. After teaching students in Macon, Savannah, Milledgeville, and Augusta, she went on to open her own school. There in the basement of Christ Presbyterian Church in Augusta, Lucy Laney set educational history into motion.

When Laney opened her school in 1883, she was focused on educating only girls, but one day, several boys appeared at the school. In true educator’s style, Laney accepted the boys at pupils. After two years, there were more than 200 African American students attending the school. A year later, the state of Georgia licensed the school. It was named Haines Normal and Industrial institute. Francie E.H. Haines was a lifetime benefactor, and donated $10,000 to establish the institute.

In 1890, the school became the first in Georgia to offer kindergarten classes for African American children. By 1912, the school Laney started employed 34 teachers, and had over 900 students enrolled. Among the most prominent students to graduate from Haines institute was the Augusta-born and internationally-known author Frank Yerby.

Lucy Laney’s community work extended far beyond the classroom doors. As a civil rights activist, Laney helped establish the Augusta Branch of the national association for the advancement of Colored People or NAACP. She was also involved in other organizations like the Interracial Commission, the National Association of Colored Women, and the Niagara Movement.

Among her major community accomplishments, Laney helped to integrate the local YWCA. She served as the director of the cultural center for Augusta’s African American community.

Because of Lucy Craft Laney's hard work as an educator, she was one of the first African Americans to have her portrait displayed in the Georgia state capitol in Atlanta.

Laney died on October 23, 1933 in Augusta.

(INFO: WMAZ)

-----------

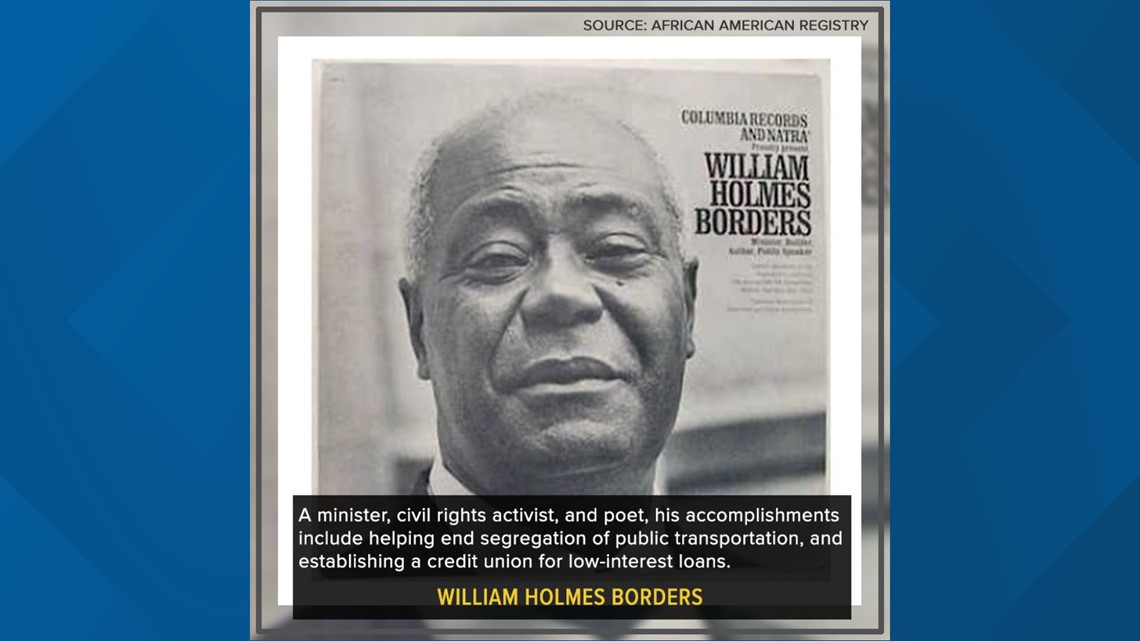

WILLIAM HOLMES BORDERS

Rev. William Holmes Borders was born in Macon, Georgia on February 24, 1905.

He became one of the influential pastors of the civil rights movement. His participation in the movement predates that of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Borders' work in both the ministry and his drive to social change was impactful. His words and work still invoke positive community change today.

Borders comes for three generations of ministers. His father was Reverend James Buckingham Borders, who pastored Swift Creek Baptist Church in Central Georgia. His mother was Leila Birdsong Borders.

William Borders graduated from Ballard Normal High School and enrolled in Morehouse College. His serious dedication paid off. When he ran out of money after two years, a group of professors appeal to Morehouse president John Hope to allow Borders to complete school. He graduated and repaid his debt to the college by working several odd jobs. He went on to the Theological Seminary at Northwestern University. It’s there that he met his wife Pate, a 1931 graduate of Spelman College.

In 1937, Borders was offered the opportunity to Pastor the Wheat Street Baptist Church on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta. While in Atlanta, Borders begin a radio broadcast that address concerns and needs of the African American community. Those recordings would later be consolidated into a single volume of work and published. Both Black and white listeners tuned in to hear information about segregation, disfranchisement, and patriotism.

Rev. Borders also worked to help Mayor William B. Hartsfield get elected in 1946. He also worked to encourage Hartsfield to hire African Americans to the Atlanta Police Department.

In 1956, Borders was among five other Atlanta ministers who were arrested for sitting on the front row of an Atlanta City Bus. He was arrested several times. The actions of the ministers ultimately helped to bring about the Supreme Court ruling which ended Atlanta’s segregation of public transportation.

Through his pastoral leadership, Borders established a credit union that offered low-interest loans, developed a church medical clinic, and operated a housing project.

Rev. Borders writing accomplishment included a 1968 portrayal of Jesus Christ titled, “Behold the Man.” The stage presentation was performed at the Atlanta Fulton Stadium, and along with many other efforts, the performance is credited for saving Atlanta and keeping the community relatively calm after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King.

Of Borders' many accomplishments, it’s his 1946 poem titled “I Am Somebody” that lives today in performances and art. People recall the poem when Reverend Jesse Jackson used it in 1971. Jackson changed Borders' original words, and the poem become an anthem supporting his National Rainbow Coalition. He also brought the poem to national attention by reciting his version to children on Sesame Street.

Borders had an unsuccessful bid for state representative, but from 2004 to 2010, his granddaughter, Lisa Borders, became president of the Atlanta City Council.

Borders died November 23, 1993.

(INFO: AFRICAN AMERICAN REGISTRY)

------------

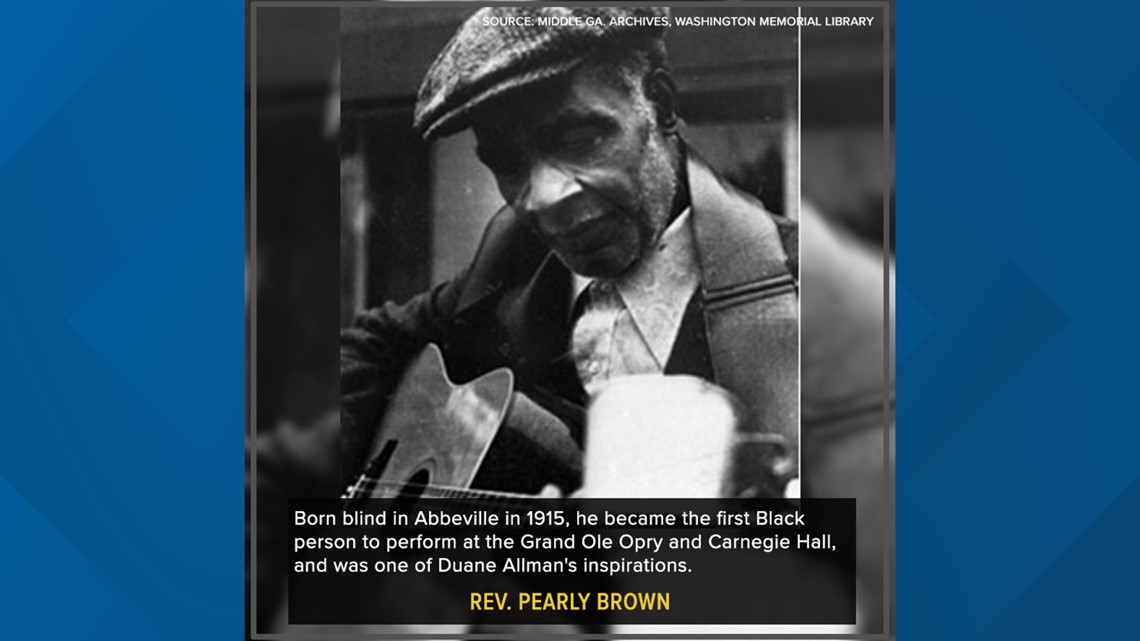

REV. PEARLY BROWN

Reverend Pearly Brown was one of the country’s last known "street singers." Born in Abbeville, Wilcox County in 1915, Brown became a singer, guitarist, and skilled accordionist. Brown described his sound as the “holy blues.” He traveled to cities around Georgia including Macon, Milledgeville, Thomasville, and Atlanta. He even traveled to Florida.

His musical journey to notoriety began with a goal of spreading the gospel through music. It resulted in Brown becoming one of the first African Americans to perform at the Grand Ole Opry, Carnegie Hall, and other national stages.

Brown’s family relocated to Americus, Georgia when he was a small child. A schoolteacher recognized his determination to succeed and arranged for him to attend Macon’s Georgia Academy for the Blind. He completed eight years of education which included Braille. He returned to Americus where he became an ordained minister at the Friendship Baptist Church.

Brown spent the 1930s as a minister and a bean picker. His began his musical career in 1939. Records show that for most of his career, Brown lived in a one-story house on Ashby Street in Americus. He lived there with his first wife, Willie Mae.

Rev. Brown was uniquely positioned by birth to live in both the pre- and post-Civil War era. Brown had a daughter named Pearl. She was active in the Civil Rights Movement in Americus and was even imprisoned for her role in the movement at the Leesburg Stockade in Lee County.

Brown and other blind musicians were often targeted by police harassment while playing on the streets. Brown recalls his own experience of getting arrest and jailed in Macon.

In a 1993 interview featured on 13WMAZ, Brown talked about how mean people were, but how he was determined to keep singing his gospel on the streets.

“There used to be some mean old folks along that time -- white folk -- some mean folks along that time”, Brown said. “Every time they thought they were going to run me off the streets, I would be right back up there picking my guitar.”

The roving evangelist picked up many admirers with his street performances.

According to an online publication about Macon’s Music History by the Macon Historic Foundation, one of those people inspired by Brown was Duane Allman. He was said to be so inspired “with his (Brown’s) bottleneck style of slide guitar that after seeing Brown, the seed was planted for Allman’s music career.”

In the early 1970s, Brown was invited to perform during Hamp Swain’s weekly gospel show on radio station WIBB. In 1993, Swain talked about meeting Rev. Brown in a Macon barber shop. Swain says he asked Brown to appear on his gospel show.

“I found him to be very interesting and I thought he had something to offer,” said Swain.

From that experience, Rev. Pearly Brown was asked to travel to perform at colleges around Georgia, including the University of Georgia.

Of course, that led to Brown becoming one of the first African Americans to perform at the Grand Ole Opry, Carnegie Hall, and the Newport Folk Festival.

Brown stopped performing on the streets in 1979. He had become ill and spent his last days in a nursing home in Plains, Georgia. He died in 1986 and was buried in Eastview Cemetery in Americus near his home on Ashby Street.

(INFO: MIDDLE GEORGIA ARCHIVES, WASHINGTON MEMORIAL LIBRARY)

-------------

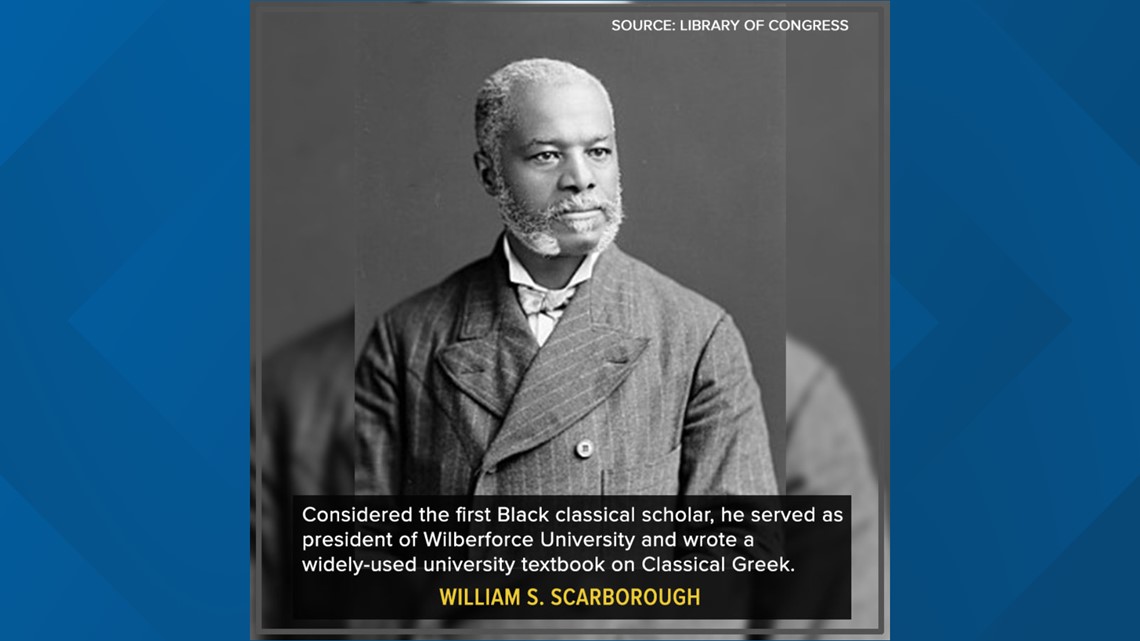

WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH

William Sanders Scarborough was born into slavery in Macon, Georgia on February 16, 1852, but with his life’s accomplishments, he challenged a common educational thought about Black students. Scarborough proved that African Americans were more than capable of succeeding with a liberal arts education. He became the first African American professional classicist in the United States. By the 1880s, Scarborough had become a world-respected scholar of Greek and Latin literature. By age 25, he was a college professor and later a university president. His influence was felt from students to U.S. presidents.

Scarborough grew up in a house on Cotton Avenue in Macon. His father, Jeremiah Scarborough, was a free Black man, and his mother was multiracial and enslaved. Scarborough inherited the conditions of his mother, meaning he was considered enslaved as well. His mother was from Savannah with a heritage that included African, Anglo-Saxon, Native American, and Spanish. Despite what Scarborough witnessed as the harshness of slavery, he was able to have a different experience because people around him risked their own lives to educate him.

Scarborough's mother was a servant slave to Colonel William DeGraffenried, a wealthy attorney in Macon. He was well-liked by both white and Black people in the community. He allowed the Scarboroughs to marry and helped to provide a stable home environment for the whole family.

DeGraffenried and friends took a great risk in secretly educating William Scarborough. Scarborough to learned to read and write from his white neighbors and a free Black family in Macon.

During that time, it was illegal to teach a slave to read and write. For the white teacher, this was an offense punishable by fine and or imprisonment. For the African American, whether enslaved or free, learning to read or write was punishable by death.

DeGraffenried allowed Scarborough to grow his education, and by the time he was 10, he not only understood reading, writing, and arithmetic, but geography and grammar, too.

After the Civil War, Scarborough was able to go to school. He attended Lewis High School in Macon. In 1869, he attended Atlanta University, later to be known as Clark Atlanta. After two years, he enrolled in Oberlin College in Ohio. Oberlin had a progressive educational history which began during the Antebellum period. In 1835, it became the first predominantly white collegiate institution to admit African American male students. A couple of years later, African American women were allowed.

Scarborough completed his degree at Oberlin in 1875. He also completed his degree at Atlanta University in June 1876. Col. DeGraffenried helped pay for some of Scarborough’s books while he was college. Scarborough returned to Lewis High School in Macon where he taught classical languages.

He met his future wife, Sarah Cordelia Bierce, a white missionary and the principal of Normal Department at Wilberforce University between 1877 to 1914. The two would eventually marry in 1881. That marriage marked another remarkable success of Scarborough’s personal life. The couple were married for 45 years. Their marriage was one of partnership with the common goal of “uplifting all of mankind through education, regardless of race or gender.”

At 25 years old, Scarborough became a professor of Latin and Greek at Wilberforce University in Xenia, Ohio In 1877. He wrote a college textbook titled "First Lessons in Greek." The book was published in 1881 and eventually became widely used in colleges and universities across the country including Yale University. Scarborough published a second book, "Birds of Aristophanes" in 1886.

In 1884, he became the first African American to join the Modern Language Association (MLA) and also joined the American Philological Association (APA). He was fluent in several classical languages and published several intellectual papers for discussion on the world stage. This elevated William Sanders Scarborough to a world-respected scholar of Greek and Latin literature. However, he did encounter initial resistance when he was prevented from presenting his own paper because he was Black.

In 1908, Scarborough was named President of Wilberforce University and continued to write and publish in linguistics.

In 1921, Scarborough was appointed by President Warren G. Harding to a post in the Department of Agriculture which he held until his death in 1926.

William Sanders Scarborough’s reach went far beyond the classroom. He influenced US presidents and other leaders. The list includes but not limited to: John Sherman, Theodore Roosevelt, William Taft, Warren Harding, A.M.E. Bishop Daniel A. Payne, Frederick Douglass, and Madam CJ Walker.

In 2001, the Modern Language Association established the William Sanders Scarborough Book Prize in his honor.

-------------

Leontine Louise Fields Espy

There are some legendary African American high school principals who poured into the foundation of success within Bibb County's educational history. Among those fantastic educators was Leontine Louise Fields Espy.

She was petite in statue but might in presence. She was never known to raise her voice but always commanded obedience from her students.

With Espy's more than 40 years in Bibb education, she touched students across Macon. Her former students, the community and her family, say Leontine Espy knew how to bring out the best in you with firmness and love.

Leontine Espy was born on January 4, 1932. She grew up in the Pleasant Hill Neighborhood. Her future as an excellent educator and singer was developed in the rich learning environment of the community. Her early years were spent as a student at L.H. Williams Elementary School.

She later went to Ballard Normal High School, located on Forrest Avenue in Macon. After high school, Espy attended Fisk University and Atlanta University, which later became Clark Atlanta. She graduated with Bachelor's, Master's, and Specialist Degrees in Education.

While attending Fisk, Espy joined the Fisk College Choir. She was greatly influenced by the legendary Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Leontine Espy trained and developed her beautiful soprano voice there. She traveled with the Fisk Jubilee Singers singing across the country.

Leontine Fields Espy's career began at Ada Banks Elementary School as a second-grade teacher in the 1950s. Her mother, Katie C. Fields, also taught at the school when Espy started.

The young Espy would later teach English at Ballard Hudson High School, where she met her husband, George Espy Jr. Both were English teachers in 1955. The couple remained there until the 1970s.

Her husband, George Espy Jr, was history-making in his own right. He would become the first African American English teacher at Mercer University and a well-known organist and pianist.

In addition, George Espy, Jr would play the music for his wife on her many singing engagements at churches across Macon. Another legendary educator and pianist, Gloria Hutchings, would often accompany Leontine Espy. Hutchings was both a childhood and college friend of Leontine Espy. The two graduated from Fisk.

In the early 70s, Leontine Espy became the assistant principal of the all-girls Lasseter High School. The Lasseter Building, which no longer stands today, was part of the Northeast High School Complex. The Mark Smith building still stands today. In the '70s, it was the all-boys building.

From there, Leontine Espy became the principal at the old Ballard A Building on Anthony Road. This became part of Southwest High School. The Ballard B Building is known today as Ballard Hudson Middle School. In 1977, the students and staff of Ballard A dedicated the school's yearbook in honor of their esteemed principal.

The next stop for Leontine Espy was the principal of Central High School. It's there where many people today may remember her most. Espy created the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program among her many contributions to student growth. She was the principal of Central High School for 16 years.

She had a remarkable impact on many people across Macon as she taught in every corner of the city. Many of her students recall her very effective communication style and how she loved and supported all of her students.

Former student, like 13WMAZ's Chief Meteorologist Ben Jones, credits Espy for giving him his start in broadcasting.

"I love this lil' lady! She gave me my start!" Ben said in a Bibb County government Facebook post when it recognized Espy. "She went on a limb to let a silly kid have a radio show on the morning announcements. I will be forever thankful for that shot. Love you, Ms. Espy!"

After leaving Central, Espy was appointed as the associate superintendent for curriculum for the Bibb County School District. She remained there until retiring in 1996.

The Espy's had two sons, George Fadil Muhammad and Gregory Warren Espy. They remember their mother as being a very loving person. However, they said with that gift of love came an uncompromising firmness that did not tolerate disobedience.

"Mom would always bring out the best in you, as far as your integrity, she had a way of making you feel very badly about not really doing what you knew was right," said George Muhammad. He said whether at home or in the public, his mother used "the right choice words that had a powerful, positive impact on people."

Muhammad notes his mom always showed people she appreciated them by sending thank you cards to everybody in her life. "She would send card on different occasions throughout the year just for acknowledgment and appreciation. she was a master at that," said Muhammad.

Even in retirement, Espy remained active in the lives of students, teachers, and administrators as friends, confidants, and mentors.

In February 2016, Espy was recognized by Macon-Bibb County Mayor Robert Reichert and commissioners for her decades of service to children.

Leontine Espy died on December 12, 2016.

(INFO: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

-----------

Cleopatra Love

We remember a Macon woman whose very name represented a love of education and love of black history.

Cleopatra Love was a strong willed and uniquely independent woman of the 1900’s. Love embraced education at an early age. She grew up and left a legacy of helping black Americans understand their rich African American heritage.

Cleopatra Love was born in Eufaula, Alabama about 1893. She was an only child of her parents, George and Laura Love, when they moved to Macon. Her mother was a designer and dressmaker and her father was a home designer.

Her father drew the plans for and build a large house on 327 Monroe Street in Macon. Love lived in that house for much of her life.

Over the years, the home became a focal point of beauty as Love always keep the yard blooming with many flowers. Miss Love was also a very attractive and stylish woman.

In retirement, Cleopatra Love saw her home as, “a wealth of materials- books, pictures, pamphlets on Negro history and the Negro contribution to this country and the world,” she explained in a December 1971 interview.

By 1957, Love created a fact sheet of African American contributions she called “Facts Seldom Heard”. Her efforts turned into a well-known resource full of black history.

At age 4, Cleopatra Love became the youngest child to attend the first grade at the Green Street Grammar School. Early reports says that it was her mother who wanted Love to start her start school.

Love’s fourth grade class was so smart that the principal at the time offered to test the students to see if they could move on to the sixth grade. While Cleopatra was in the sixth grade, a man by the name of L.H. Williams was her teacher.

He suggested that some of his students move ahead to the eighth grade located at Ballard Normal High School. Cleopatra was among those students.

By the time she was 8 years old Love had decided she wanted to be a teacher. In the December 21,1971 interview with the Macon Telegraph, Love told the story of the moment she made her life changing decision to teach.

She explained that she was playing with paper dolls she had cut out of her mother’s fashion magazines. “They all had names and were lined up as in a classroom and I was teaching them. I only asked questions that I know the answers to and would answer for the dolls, “Love said.

“Then it came over me that I wanted to be a teacher. I went in to where my mother was sewing. As usually I leaned up against the sewing machine and said, ‘Mamma, I decided to be a school teacher,'" she continued.

Love said she never wavered from that ambition, and never regretted the decision.

Cleopatra Love went on to attend Atlanta University for her undergrad and masters. She also completed graduate study work at the university of Chicago and New York University.

She worked at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee teaching Black History, and later at Booker T. Washington High School in Atlanta. She taught there for 25 years.

Love was a member of The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. She was also the cousin of Walter E. Washington. He is listed as the first African American mayor of a major city in the United States, and in 1974 became the capital's first popularly elected mayor since 1871.

While in Washington D.C., Love says she was also invited to a meeting of foreign delegates and witness the historic dedication of a portrait and building named for Carter G. Woodson, “the Father of Negro History.”

Love said Dr. Woodson wrote the first Negro history called, ‘The Negro in Our History’ which she used as a textbook for many years. Woodson organized “The Association for the study of Negro Life and History.”

He was the president until his death and is responsible for the first Black History recognition, “Negro History Week in 1926.” This week has turned into the nationally recognized Black History Month.

While teaching at Booker T. Washington High, Love says she recalls when then Governor Eugene Tallmadge passed a law in that basically said, “Negro history could not be taught in any school which was receiving state funds”.

Love said the principal at the time told her she could take as many of the school textbooks she wanted because "...they’ll never be used again”. Love said in the 1971 interview, “I’d love to have lots of them now to give to people to read.”

Once retiring from teaching, Cleopatra Love continued to share black history facts, and much of that information include the facts that are still not widely known by most people today.

Love niece was Macon’s community leader and Civil Rights activist, Ozzie Bell McKay.

Cleopatra Love literally collected hundreds of “little known facts” that she made available at no cost to anyone who was interested.

Miss Cleopatra Love died in Macon on May 15, 1982.

-----------

Louis Persley

Macon’s booming black business district of the 1900s produced may successful individuals. Among them was a talented architect named Louis Persley.

According to Historic Macon, Louis H. Persley was the first African American to register with Georgia’s State Board of Architects on April 5, 1920. He also had a street in Pleasant Hill named in his honor.

He is also very possibly the part of the nation’s first black architecture firm that was founded in July 1920. The Taylor and Parsley partnership came about in part because of his teaching position at the then Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

At the time it was virtually unheard of for a person of color to become a professional architect. Louis Persley was born in Macon’s Pleasant Hill community. His parents were Maxie and Thomas K Persley. He also had three other brothers. The family lived at 215 Madison Street, the address of the property at that time.

Now as for Louis Persley’s birthday and his name, both have been recorded differently over the years.

Historic Macon’s records show Louis Persley's birth year as 1890. If you research equally creditable sources, Persley’s birth year is listed as 1888. Historic Macon says multiple spellings of his name have also been found.

According to Historic Macon, different registries have his first name spelled both “Lewis” and “Louis”. Census records form 1900, 1910, and 1920 spell his family name these different ways: “Pearsley”, “Parfley” and then “Persley”. The spelling of his middle name has also been different. There are “Hudson” and “Hudison”.

When the Macon Street was named in his honor it was spelled “Pursley”. Today, people are very familiar with Pursley Street, which is also where the historic L.H. Williams Elementary school is located.

Louis Persley’s education included local public schools. He then went to Lincoln University, a historically black institution near Oxford Pennsylvania. According to Historic Macon, he graduated for Carnegie Institute of Technology with an architecture degree in 1914. Today, it’s known as Carnegie Mellon University.

When Persley graduated he was offered a job at Tuskegee Institute, known today as Tuskegee University. Louis Persley taught mechanical drawing until 1917. Persley volunteered to fight in World War I. Persley’s future architectural partner, Robert Robinson Taylor, was the director of the college’s Mechanical Industries Department at that time.

When Persley returned from the war, he was promoted to head of the Architectural Drawing Division. Among the many structures designed by Persley included several buildings on the Tuskegee campus. Work was done as a part of the Taylor & Parsley Architect team. In 1921 the men completed the James Hall, a dorm for nursing students. Another building designed was the Sage Hall, a dorm for young men and the future quarters for the Tuskegee Airmen. Much of the campus was touched by the Taylor & Parsley architecture styles including Logan Hall, Armstrong Science Building, and the Hollis Burke Frissell Library.

Persley also designed the new First African Methodist Episcopal Church in Athens. That church’s work began in 1866. It was one of only a few projects completed in Georgia. A commemorates marker stands in front of the First AME Church. It was placed there in 2006.

Records show that Persley was involved in more than a dozen construction projects. He worked on only two in Macon. There were the Chambliss Hotel in 1922, and a two-story brick and stone funeral home in 1928.

July 13, 1932, Louis Persley died at age 42. His death was the result of kidney failure. He was buried at the Linwood Cemetery in Pleasant Hill in Macon. On his gravestone his name is spelled Louis “Pursley”, the same as the Pleasant Hill Street sign honor.

Gloria Walker and the Chevellas

This Black history moment steps back to the late 1960s and reflects on the fame of an R&B music group made up of Milledgeville high school kids. While their chart-topping notoriety was short-lived, there is no doubt the young performers left an impact on R&B music history.

Gloria Walker was the lead singer of the Chevelles and a break-out star in her own right.

Her strong voice and stage performances created such a buzz that she even received many offers to go solo, including from the Godfather of Soul, James Brown.

By the time the members of the soul band had graduated from high school, they had a hit record and had performed at the Legendary Apollo Theater Harlem. In 1968 the Chevellas were on top of the music charts alongside big names like Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye. Unfortunately, the young singers did not get to hold on to their amazing success, but they hold a spot in R&B music history.

In 1967 Gloria Walker and the Chevellas were founded by Curtis Davis. Most band members were Baldwin County’s J.F. Boddie High School students. This was a Milledgeville school created for African American students in 1956 during the era of segregation.

The group was founded by Curtis Davis, who had just graduated from Boddie High School. While he did not play any instruments, he reportedly had an “ear and heart for music.”

The female lead was, of course, Gloria Walker. Curtis selected members who played in the band in high school or church and had some musical talent.

Donzell Reeves was chosen to play the keyboard and was the only member who had also graduated.

“The remaining band was still in school and included: the Havior brothers, Oscar on guitar and James, nicknamed HeyBoy, on drums; Emmitt “Red” Green on saxophone; and Lonnie West on sax. Julian “Butch” Edwards played sax with them part-time, and later, Henry “Boot” Mitchell joined them on trumpet.”

Gloria Walker and the Chevelles performed locally around Milledgeville, Macon and central Georgia. Their history was made when they recorded their cover song in Detroit.

“Talking About My Baby” was a song that had an introduction of Gloria Walker talking about how a boy broke her heart.

The song was the Chevelles cover of “I’d Rather Go Blind,” which Etta James had made into a hit one year earlier.

“Talking About My Baby” was released on Flaming Arrow Records in October 1968. The song was Number 7 on the R&B charts by early November and No. 60 on the Hot 100.

That set the stage for the historic Gloria Walker performance at The Apollo Theatre in Harlem. She was still in high school at the time.

Over the years, Gloria Walker would continue to receive offers, including twice to tour with James Brown. The young singer reportedly rejected offers that required her to leave her band because she said she did not want to leave her “music family.”

Both Chevelle and Gloria Walker went on to make music individually over the years.

Many people do not know the details of this incredible story of Gloria Walker and the Chevellas or even know their Milledgeville beginnings that landed them on the music charts.

To understand and appreciate the value of their story, you must read the whole journey in this article called Salvation South. This is the only known record featuring the voices of the living band members and interviews with people who hold this music history close to their hearts.

Photos credit of Gloria Walker and the Chevelles goes to Georgia College Special Collection.

While some of the Chevellas band members are still alive today, Gloria Walker died in 2006.

Lena Horne

Long before the legendary Lena Horne graced the silver screen, she lived in Macon Georgia’s Pleasant Hill community. As a child she not only lived in Macon, but in Fort Valley as well. The dancer, singer and actress shared the details of her fond memories of Macon memories in her memoir titled Lena. The book was published in 1965.

Known for her poise and beauty, Lena Horne was not only an entertainer, but a Civil Rights Activist. She worked with civil rights groups like N.A.A.C.P. and refused to play roles that stereotyped African American women. Lena Horne became known as one of the top African American performers of her time. She was the first African American signed to a long-term studio contract.

Born Mary Calhoun Horne on June 30, 1917, Lena Horne lived a short time with her parents in Brooklyn New York. Both of her parents were of mixed heritage of African American, European American, and Native American. Her father was a banker and professional gambler. Her mother was an actress who traveled a lot as a member of various theater troupes. Horne’s parents separated when she was three years old. She lived with her grandparents for a while in New York and then later traveled on the road with her mother.

In the book Lena, Horne talks about how she found herself living with strangers, at least to her. She said these people where family and friends of her mother. As her mother traveled with various a stage shows trying to pursue her dreams, she left Horne in the best places she could. In the book Horne highlights the details of some of her experiences while living in cities like Jacksonville, Miami, and Macon.

Lena Horne said she was “happy” living in Macon. Horne’s mother, Edna, first brought her to Macon where she lived in a small house owned by two older women – a great-grandmother and her daughter and two other children who were grandchildren of the younger woman.

“I was happy there. The old lady would read the Bible to us, or maybe just tell Bible stories to us, “said Horne. In the book she talked about the daily home life, enjoying the busy downtown Cherry Street, and school experiences.

“But the most important thing I learned there was how good people could be. Those women with whom I lived were not self-righteous, but they were godly-good, hard-working Negro women, getting along like so many of them without a man’s help,” said Horne. “They were kind to me in every way,” said Horne.

Horne moved to Macon in 1927 and sometime after that her Uncle Frank moved her to Fort Valley. Horne said she remembers playing in the front yard of the house when Uncle Frank arrived and told her he had come to take her to Fort Valley. He was Horne’s father’s brother, and according to her book, he was the one brother Horne’s mother liked. Horne says her Uncle Frank was a teacher at Fort Valley Junior Industrial College. He was also a published poet who was a member of the Negro advisory committee called the “The Black Cabinet.” Lena Horne says she lived on campus in the girl’s dormitory until her uncle got married. A year later, Horne said she moved in a nice home with her uncle and his wife in Fort Valley.

At age 16, Horne dropped out of school and back in New York she began performing at the Cotton Club in Harlem.

The entertainment bug may have bitten Horne naturally because of her mother’s work. However, Lena Horne achieved true stardom.

Her pose and grace helped her get noticed by MGM studios. While with MGM, she dazzled audiences in musical films like Cabin in the Sky which featured an all-black cast in 1943.

She also made a name for herself in the film Stormy Weather. Also, a 1943 American musical, it was filmed, produced, and released by 20th Century Fox.

Not only was Lena Horne one of the most popular African American performers of the 1940 and 50’s, but she was pioneer.

At the 74th annual Academy Awards in 2002, Halle Berry thanked Lena Horne for paving the way for her to become the first black recipient of a Best Actress Oscar.

Lena Horne was married to Louis Jones from 1937 to 1944, and they had two children. She later married Lennie Hayton, a white bandleader, in December 1947 in Paris, France. The couple kept their union a secret for three years. Reportedly, marriage was significantly impacted by racial prejudice, and they separated in the 1960s but never divorced.

Lena Horne had many stage and film performances over the years. Among one of her popular musical films was The Wiz in 1978. Horne stared as Glinda the Good alongside Diana Ross, performing “Believe in Yourself,” which became another musical hit for Horne.

Lena Horne died of heart failure on May 9, 2010, in New York City.

Chance Simpson

During the month of February, we celebrate the African Americans, well- known and unknown. Their place in history is solidified by their accomplishments both the past and the present. However, it is equally important to turn our attention to the future and look to the young Black Americans carving their place in history. There are many young African Americans achieving against odd and excelling with talents and skill all around Central Georgia.

We travel to Marshallville to meet one of them, 19-year-old Chance Simpson. He is well on the way to making his mark in History. The John Hopkins University sophomore has earned a university internship as a cybersecurity software engineer. Simpson is a double Computer Science economics major.

“I have a passion for computers have a passion for learning. And I also want to surround myself with greatness. John Hopkins was the choice for me,” said Simpson.

Chance Simpson’s name is certainly familiar to many people in Macon County and Central Georgia. He has already achieved academic and sports success before, he was accepted into Johns Hopkins.

“I just want to surround myself with great people; people as smart as me, people who are smarter than me, people who are doing things ten times greater than me,” said Simpson.

At age 16 Simpson graduated from Macon County high school in 2020. Before archiving that goal, he signed up as a dual enrollment student at South Georgia Technical College at the start of his 10th grade year. Simpson graduated with his associate degree in Computer Networking Support just a few weeks shy of graduating from high school.

Soon after that he learned he was one of 304 students admitted as part of Johns Hopkins University’s Early Decision II program. He earned a full academic scholarship worth $79,189 per year and worth $316,756 for four years.

But it doesn’t stop there. Chance Simpson is a student athlete currently on the Johns Hopkins University track and field team where he is excelling.

We Asked Chance Simpson how did he achieved all of this, and his answer reflected years of wisdom, surprisingly coming from a young man.

He first advice to his peers is to find out their talented and what they are passionate about. Using himself as an example Simpson says he loved medicine but changed his major from anesthesiology because he did not like all the classes that followed.

“Do something that you love, do something that you might pursue or have a passion for because you're going to keep chasing that goal, you're going keep doing what you want to do, “said Simpson. He also said they should grow and develop those skills through train and higher education like technical school or college.

But he says the real key is to believe in yourself.

“I believe in the laws of the universe, which is like the Laws of attraction. So, the energy you put into the world is the same energy that will return to you in greater form.”

Simpson said if you are negative, and only speak about what you can’t do, expect the universe to return those words to you and make them true.

“All through my process I said, ’I will be great, I will be smart, I will graduate at the top of my class, I will graduate with two degrees.” And now that I have been saying these things into my life, the universe, God has blessed me with a great way to get into John Hopkins.”

Chance Simpson’s Future plans include operating his own business. He wants to inspire and help other people.

He adds, “I want and inspire other people in the same predicament as me, saying anything is possible if you put your mind to it.”

Chance Simpson has been recognized for his achievements in Macon County. This Marshallville resident is making his parents, Ronald, and Kesha Simpson proud, and building his own path to Black History.