BOISE, Idaho — A city of Boise human resources investigation from 2018 found a police officer’s claims about his supervisor engaging in unethical behavior to be true — but did not confirm his claim that he was retaliated against, according to a report by the Idaho Press.

A district judge is examining that report, along with another third-party report of roughly the same length, to determine what information is privileged and what should be released to the officer's attorneys. The reports, both part of the same investigation, are each roughly 300 pages long.

The city has refused to turn over either report to the officer who filed the complaint, Cpl. Norman "Denny" Carter, or his attorneys. Howard Belodoff, one of Carter's attorneys, told the Idaho Press in an email Thursday that "the judge already ruled that the reports did not have a blanket attorney client or work product privilege protection," but he said the judge is determining what exactly is privileged in the reports.

Carter in 2018 filed a whistleblower lawsuit, claiming that Boise Police Lt. Greg Oster “openly” sold weapons, both to officers and the public, through his private company out of his police department office.

Carter also claimed Oster, who became his supervisor in 2015, retaliated against him after he raised concerns, and that other officials failed to prevent the retaliation.

The city hired an outside attorney to investigate, to whom Carter made another claim: that the police department had falsified training records.

In multiple court documents, city attorneys say the investigation reports are protected by attorney-client privilege and work product exemptions. Brady Hall, attorney for the city, made the same argument in court Sept. 16, saying the reports were part of preparation for litigation.

Mike Journee, spokesman for the city, said he could not discuss the lawsuit, since litigation is ongoing.

In August, 4th District Court Judge Jonathan Medema agreed to examine those reports and decide what is privileged information. He has not yet made a final determination, but in his decision to look at the documents, he confirmed the results of the city’s investigation. A June 2018 letter from the city to Carter's attorney also confirmed the results of the investigation. That letter was put in the court record as part of a declaration from a city attorney in June.

THE INVESTIGATIONS

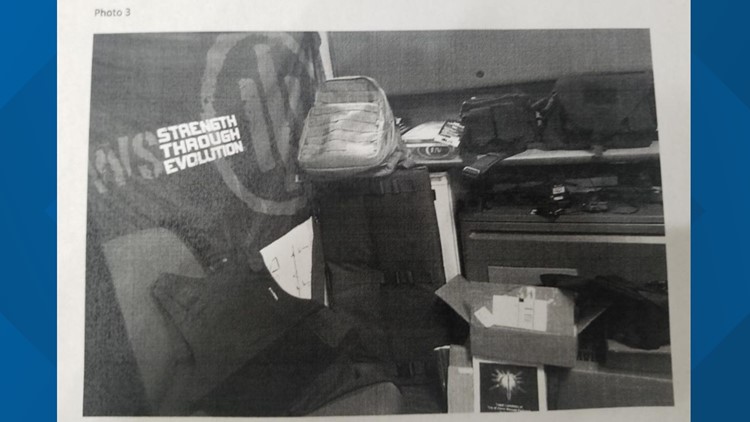

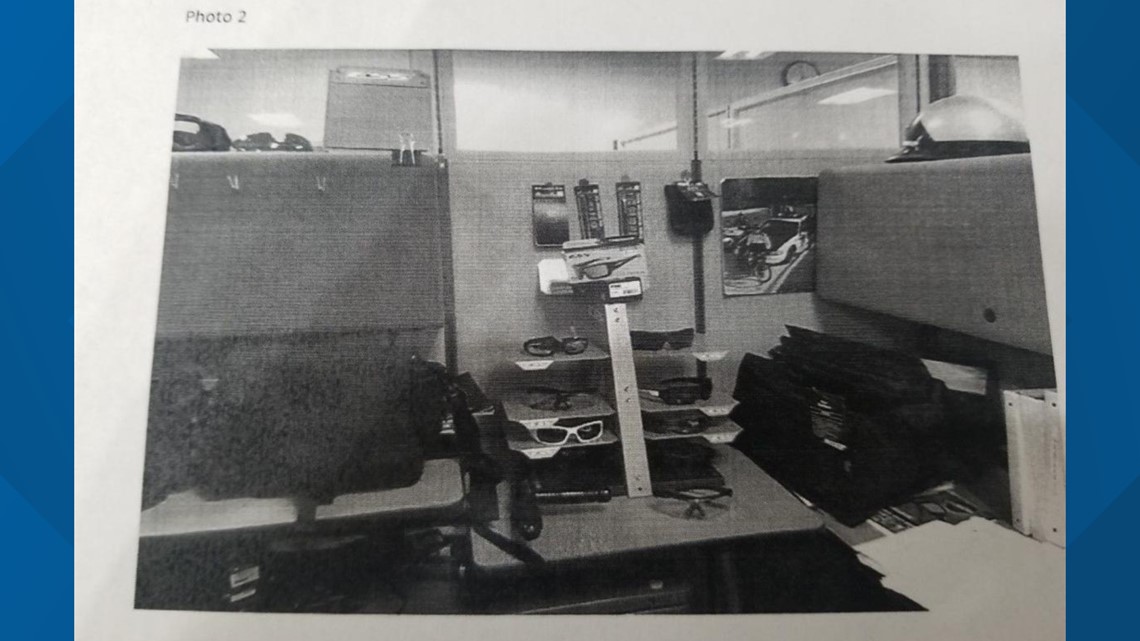

Carter, in December 2017, asked his attorney to write a letter to Boise Mayor Dave Bieter about his concerns. Included with that letter are photographs of what Carter said was the storefront for Oster's business. Those pictures are included in this story.

After Carter sent the letter, the city hired a third-party attorney to investigate.

"Lieutenant Oster engaged in various activities that violated the City's Code of Ethics and Fiduciary Policy," the June 2018 letter to Carter's attorney reads, further stating that complaint had been "sustained."

During the investigation, Carter also told the attorney, Patricia Ball, that the police department was falsifying training records and accreditation materials, according to a court order from Medema on Aug. 12.

However, Ball apparently found those claims to be untrue, Medema wrote in the order.

The whistleblower lawsuit is ongoing, with a court date scheduled in November. On Sept. 4, Carter filed another amended complaint in a separate case, claiming the retaliation had continued even after he'd filed the first whistleblower case. Attorneys have asked to combine the two cases, but that has not happened yet.

CLAIMS OF FALSIFYING RECORDS

Carter met with Ball for the first time in January 2018, he wrote in a May 20 declaration to the court.

“Ms. Ball informed me she was not the city of Boise’s attorney and that she would be serving as an independent fact-finder who was neutral,” Carter wrote. “… During my first interview with Ms. Ball, Sarah Martin, from the city’s human resources department, was present, along with my attorney. No attorneys from the city’s legal department were present.”

In the declaration, Carter wrote he later provided Ball with “additional information and documentation of ethical violations.”

In early February 2018, he met with Ball again, he wrote.

“I provided Ms. Ball with documentation of Lt. Oster’s ethical violations which included, but are not limited to, conducting private business while on duty, selling weapons on behalf of his private business, at the Boise Police Department’s headquarters and falsifying POST training records,” Carter wrote. “I also alleged that the command staff at the Boise Police Department falsified accreditation materials through the Idaho Chiefs of Police Association.”

In another complaint related the matter — filed Sept. 4 as its own case — Carter’s attorneys claimed Boise Police Chief Bill Bones falsified those materials to gain accreditation.

“Cpl. Carter also alleged during the investigation that Chief Bones violated the Idaho Chiefs of Police Association accreditation requirements by intentionally falsifying policies required to obtain certification,” according to the Sept. 4 complaint. “The violations Cpl. Carter brought to the attention of the City’s investigator were committed with the knowledge and acquiescence of BPD command staff, including Capt. Lee, Deputy Chief (Eugene) Smith, Chief Bones and Capt. Burch.”

Ball appears to have found those complaints to have been untrue, Medema wrote in his Aug. 12 order. Among the documents Carter’s attorneys asked for were “documents related to the Boise Police Department accreditation and communications to the Idaho Chief of Police Association Law Enforcement Accreditation Program.”

The city’s attorneys objected to fulfilling that request, claiming they weren’t relevant to the lawsuit.

“The court agrees,” Medema wrote. “During Ms. Ball’s investigation, Mr. Carter apparently made a new complaint to her about his supervisor having to do with the accreditation process. Ms. Ball apparently found these complaints to be untrue.”

HUMAN RESOURCES INVESTIGATION

The investigation continued after Ball had finished her report, Medema summarized in his Aug. 12 order.

“It is unclear what her ‘impartial, unbiased fact-finding investigation’ uncovered,” the judge wrote. “Subsequently the City’s Human Resources Department took over the investigation. It concluded that Mr. Carter’s allegations that the other police officer (plaintiff’s supervisor) was engaged in unethical behavior were true. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it also concluded that any adverse employment actions taken by plaintiff’s supervisor were not in retaliation for Mr. Carter’s having brought unethical behaviors to the attention of others.”

The report from the human resources department also numbered more than 300 pages. When Carter and his attorneys asked for it, the city claimed it, too, was privileged information.

"As indicated above, after Ms. Ball completed her written report, it is not clear who she sent it to or why," Medema wrote in his order. "For unknown reasons, Ms. Martin with the Human Resources Division then started talking to witnesses. Ms. Martin then did a 'report.' The court cannot tell the difference between the two. The court assumes the city asked Ms. Martin to do something that Ms. Ball had not."

The Idaho Press in July requested results of the investigation. The police department's response said the results were a personnel matter and not subject to public release.

ANOTHER COMPLAINT

Oster was put on administrative leave in early 2018, as the inquiry into Carter’s complaints began. Oster retired from the Boise Police Department a few months later, in the summer of 2018.

Carter is still a Boise police officer. He claims the retaliation against him continued after the whistleblower lawsuit was filed.

For example, in late 2018, according to the Sept. 4 complaint, Carter and the department agreed he would serve on the department’s training unit for six months. He returned to the unit on Jan. 6, and was removed on May 11.

“Cpl. Carter was removed from his duties in the Training Department without explanation,” according to the complaint. “Chief Bones was aware of this retaliation and approved and ratified the decision to terminate Cpl. Carter’s assignment.”

He was deprived of overtime opportunities from May 12 through July 6 as a result, according to the complaint.

In February, according to the complaint, Bones mentioned Carter’s complaints in a department-wide email, writing there were “an amazing number of false facts about current and some recent past investigations and the employees involved,” the complaint alleges.

More recently, Carter applied for a job in the department’s gang intelligence unit. As part of the application process, he asked an officer, identified as "Lt. LeBar" in the complaint, for a reference. Acceptance onto the gang intelligence unit was governed by a selection committee, made up of officers and at least one representative from the prosecutor’s office.

The lieutenant “submitted a reference that was characterized as petty, unprofessional and retaliatory,” by one of the officers on the selection committee, according to the lawsuit.

“Chief Bones was aware of Lt. LeBar’s retaliatory reference because he had to approve Cpl. Carter’s job assignment and had access to the evaluations,” the complaint claims.

On Sept. 16, Bones announced his plans to retire on Oct. 24. When asked that day if the decision had to do with the lawsuit, he said it did not.

“I’m absolutely not being forced out,” he said. “The mayor is great. This is all my idea.”

PRIVACY OF RECORDS IN DISPUTE

Belodoff, Carter’s attorney, told the Idaho Press the civil suits against the city are still in their infancy. He said attorneys need to see the reports written as a result of the city’s investigation.

“Where we’re at is waiting for us to receive the investigation taken by the city after Carter complained,” he said.

He said he has not seen the report. City attorneys claim it's protected by attorney-client and attorney-work product privilege. Judge Medema was not convinced of this argument.

“Ms. Ball was essentially acting as a private investigator,” the judge wrote in his Aug. 12 order. “The court is not persuaded that every statement in her report, therefore, was a privileged communication under attorney-client privilege. Certainly the statements by Mr. Carter and the other witnesses she interviewed were not privileged communications; none of those persons were seeking her legal advice.”

The city also claims it enlisted Ball’s help because it was preparing for litigation — and the city’s attorneys pointed to Carter’s December 2017 letter as the reason they thought they would be sued.

“The court is not persuaded,” Medema wrote. “The letter was written to Mayor Bieter after Mr. Carter had complained to two deputy police chiefs and could perceive no response. The letter indicated its purpose was to ‘make [the mayor] aware of the ethical violations committed by [his supervisor] and to request your help in resolving Cpl. Carter’s claims. While the letter inferred that Mr. Carter was willing to sue, it expressly stated he preferred not to; thus, he was hoping the Mayor could help ‘rectify’ the situation.”

Carter’s attorneys asked Medema to examine the reports “in camera” — a process allowing a judge to privately review privileged information. They hope he will then make a decision on what is privileged information, and what the city must release to attorneys.

The judge did grant two requests to order the city to release records. The lawyers asked for "copies of any sustained complaints for ethical violations by any city of Boise police department employee from 2013 through 2018," according to the order.

They also asked for "any grievances, complaints, referrals to Internal Affairs, Internal Affairs investigation files, and/or documents reflecting discipline imposed relating to any allegations that ... an employee of the City of Boise Police Department violated any city of POST ethical rules or was engaged in private business while on duty."

"The city argues that production of the records would be unduly burdensome for 'the city and its employees,'" Medema wrote in the order.

He also wrote the city believed production of the documents would have a "chilling effect" on future internal affairs investigations.

He was unconvinced by both arguments. While the judge ordered the city to give those records to Carter, he also ruled Carter could only share them with his attorneys. In an email Thursday, however, Belodoff told the Idaho Press he had not yet received the records.

In court Sept. 16, Medema said he would not rule on every statement made in the more than 600 pages of reports.

“I don’t intend to go through and rule on every statement made to every person whether this is work product or not,” Medema said.

He said he would more likely “file a decision saying ‘here’s the materials I find are privileged, everything else is not.’”

“We still contend that all of the documents were prepared in anticipation of litigation, and it’s regardless of what statements were made in those documents,” said Hall, one of the city’s attorneys, at the Sept. 16 hearing. “We have a declaration on file of the city clerk or the city attorney … stating that this was all done pursuant to litigation.”

Hall asked Medema to give attorneys another 60 days to decide if the original whistleblower case should be combined with the new case Carter filed this year. Medema granted that request, setting a Nov. 18 court date.

The next court date for Carter’s 2019 case is Nov. 6.