BOISE, Idaho — Editor's Note: This article was originally published by the Idaho Press.

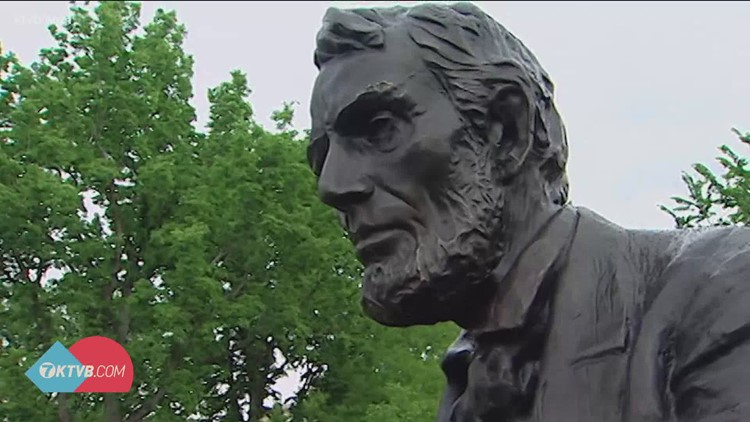

Many Idahoans were shocked to learn in early February that activists had desecrated Boise’s “Seated Lincoln” statue with red paint. Lincoln is a beloved historical figure to many who consider him the father of Idaho for creating the Territory of Idaho in 1863.

Shock was the point of the peaceful protest. The red paint — meant to signify blood — was made of nontoxic, biodegradable chalk that washes away easily. The protest, which also included hand-lettered signage, came on the first day of Black History Month and was meant to highlight Lincoln’s complicated history with race.

The statue, located in a grassy area in Julia Davis Park east of the Idaho Black History Museum, is an enlarged replica of the famous image of Lincoln seated on a bench created by Idaho-born sculptor Gutzon Borglum, according to the city of Boise website. Borglum, best known for Mount Rushmore, created the original memorial sculpture in 1911. The original is located in front of the Essex County Courthouse in Newark, New Jersey.

The city of Boise website notes that according to Davis family legend, Tom Davis, an early Boise pioneer, was acquainted with Lincoln in Illinois in the 1840s before he migrated west. In 1907, land Tom Davis donated to the city of Boise became Julia Davis Park. Borglum’s son, Lincoln, who was named after his father’s favorite president, was himself a famous sculptor and finished Mount Rushmore after his father’s death in 1941.

Lincoln is remembered as a national hero for signing the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863. The proclamation, which came at a key time in the Civil War, was a catalyst for the end of slavery in the United States. While Lincoln is celebrated across the country for his efforts to end slavery, his complicated history with racial equality — in a country still grappling its own racist past — is less known.

Activist Samantha Hager with Peaceful Roots for Change told the Idaho Press in February that members of that organization, alongside Black Lives Matter Boise and antifa Boise, wanted to bring that history to light via the protest.

Many of those involved in the statue protest are teachers and professors, who have studied history, or are political activists, Hager said in February. Lincoln’s complex story and his problematic relationship with Native Americans, may be worth re-examining, they say.

Lincoln is “the one who ordered the largest mass execution in American history, the Dakota 38,” Hager said after the protest.

In 1862, 38 Santee Sioux were executed by hanging by the U.S. government in Minnesota. Lincoln personally reviewed and signed off on the execution of 39 of the 303 Dakota warriors who had been convicted by a military commission and sentenced to be executed for their alleged roles in perpetrating massacres during the Dakota War of 1862. (One of the 39 executions was later suspended.) The sentences of 265 others were commuted.

According to reporting by The Associated Press, the original trials were a farce, some taking as little as five minutes. In addition, the Native Americans were denied counsel and did not understand what was being said.

Former University of Idaho law professor Angelique EagleWoman, a Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota, who now teaches at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, Minnesota, criticized Lincoln’s actions in an Indian Country Today article in December.

“I think he should have followed general military practice at the time,” she told the publication. “They should have been released. He made a political decision, made based on the racial hatred … Lincoln was a lawyer, knew that this was improper.”

In 1863, during Lincoln’s presidency, the Bear River Massacre in southeastern Idaho caused at least 250 Shoshone deaths, and as many as 370, Raymond Krohn, Ph.D., a professor and historian at Boise State University, said. In 1864, one year before Lincoln’s death, the Sand Creek Massacre in southeastern Colorado resulted in the deaths of at least 150 and as many as 450 Cheyenne and Arapaho people. Death estimates are debated, and one puts the Bear River Massacre at 493 Shoshone deaths, the worst against Native Americans in U.S. history according to a 2016 article from Smithsonian Magazine.

Another Smithsonian Magazine article from 2014 reported that it took months for news of the Sand Creek Massacre to reach Washington, D.C., but that as soon as it did in 1865, both the Congress and the military launched investigations. A Congressional committee ruled that the attack’s leader, Col. John Chivington, had “deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre” and “surprised and murdered, in cold blood” Indians who “had every reason to believe that they were under [U.S.] protection.”

Many of those killed in the attacks were women and children.

“What’s striking about both massacres is that militia men attacked indiscriminately by killing men, women, and children. In both instances, militia men mutilated the dead or dying,” said Krohn.

Though it’s a historian’s role to understand historical figures and events rather than to pass judgement, Krohn said, “It’s a problematic relationship between Lincoln and First People.”

That’s not a widely known or widely held view.

David Leroy, former Idaho attorney general and lieutenant governor who has studied Lincoln extensively, said, “While Lincoln was a man of his times, his achievements helped build the positive forces and facts in our time. I frankly don’t have any problem with local communities and modern people reevaluating their public monuments and their understanding of people past.”

Lincoln is intrinsically tied to Idaho, Leroy said. Lincoln created the Idaho territory in part to encourage the rapid development of mineral wealth and resources. Idaho gold was sent to the mint in San Francisco to produce funding for the Union Army.

The Homestead Act of 1862, which created Idaho territory on what had been Native land, was also intended to prevent the expansion of slavery into the Western territories by giving land to small farmers; the vast majority of the 1.5 million people given land were white.

Native Americans were not given citizenship until 1924 under the Indian Citizenship Act and so were excluded from the Homestead Act. Some were given citizenship in exchange for accepting parcels of land under the Dawes Act of 1887, which was intended to force assimilation into Euro-American culture.

The Southern Homestead Act of 1866, part of Reconstruction and intended to grant 80 acres of land to freed slaves in exchange for a small fee, was opened to white Americans in 1867 and ultimately resulted in approximately 28,000 people receiving land, only between 4,000 and 5,500 of whom were Black.

Boise Mayor Lauren McLean said in response to the February protest, “At a time when our democracy is fragile, this is particularly disturbing as President Lincoln sought to keep our fractured nation together and to address the scourge of slavery — losing his life for it. On the first day of Black History month, it’s essential to honor those in our community, reflect on our past, and work together for a better future. This terrible act detracts from progress and is an affront to those who toil daily for civil rights.”

According to a Jan. 6, 2020, article on history.com, Lincoln hated slavery, and considered it immoral.

“If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal;’ and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another,” he said in a now-famous 1854 speech given in Peoria, Illinois.

Lincoln was not an abolitionist despite ending slavery. He made public statements during his campaign for then-Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas’s seat in Congress in 1858 and asserted the superiority of white people.

“I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and Black races …There is a physical difference between the white and Black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And in as much as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race,” Lincoln told the crowd.

He added, “I do not perceive that because the white man is to have the superior position the negro should be denied every thing. I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must want her for a wife.”

Lincoln additionally expressed views that the legal distinction between individuals of the same community, “founded in any such circumstances such as color, origin, and the like, are hostile to the genius of our institutions, and incompatible with the true history of American liberty. Slavery and oppression must cease, or American liberty must perish.”

Historians, looking at Lincoln’s legacy in that context, have argued that Lincoln cannot be judged through today’s lens, citing the concept of “presentism.” Lincoln’s views on race evolved notably for a white male living in a society that propagated white superiority. As a politician, Lincoln served a moderate role.