BOISE, Idaho — A panel of Idaho lawmakers heard contentious testimony Wednesday on the state's education standards for science.

The Idaho Content Standards on English language arts, math and science are heavily based on the Common Core standards used by more than 40 states to describe what students should know after completing each grade.

The Idaho House Education Committee heard testimony on the English and math standards last week, opting not to make a decision on whether to approve the rules until testimony is heard on all the subjects. A vote on the standards could come Friday.

Republican Rep. Dorothy Moon of Stanley testified against the science standards, saying they don't talk positively enough about logging, mining and other natural resource-based industries. Last week, Moon also testified against the other educational standards in English and literacy.

"I was a science teacher, and I had what was called a comprehensive science degree" that allowed her to teach biology, chemistry and several other science classes, Moon told the committee. "Science is not political science, but today you have to wonder."

She said the science standards on energy resources don't paint some renewable resources — such as logging and hydroelectric power — in enough of a positive light, in part because they include information about erosion from deforestation and potential habitat loss from dams.

"If you have a student, and let's say his father is in the logging industry ... how is that kid supposed to go home and talk to his dad?" Moon said. "This is a mental health issue that we're going to tap into. They're going to have to confront their parents: 'Why are you a logger?'"

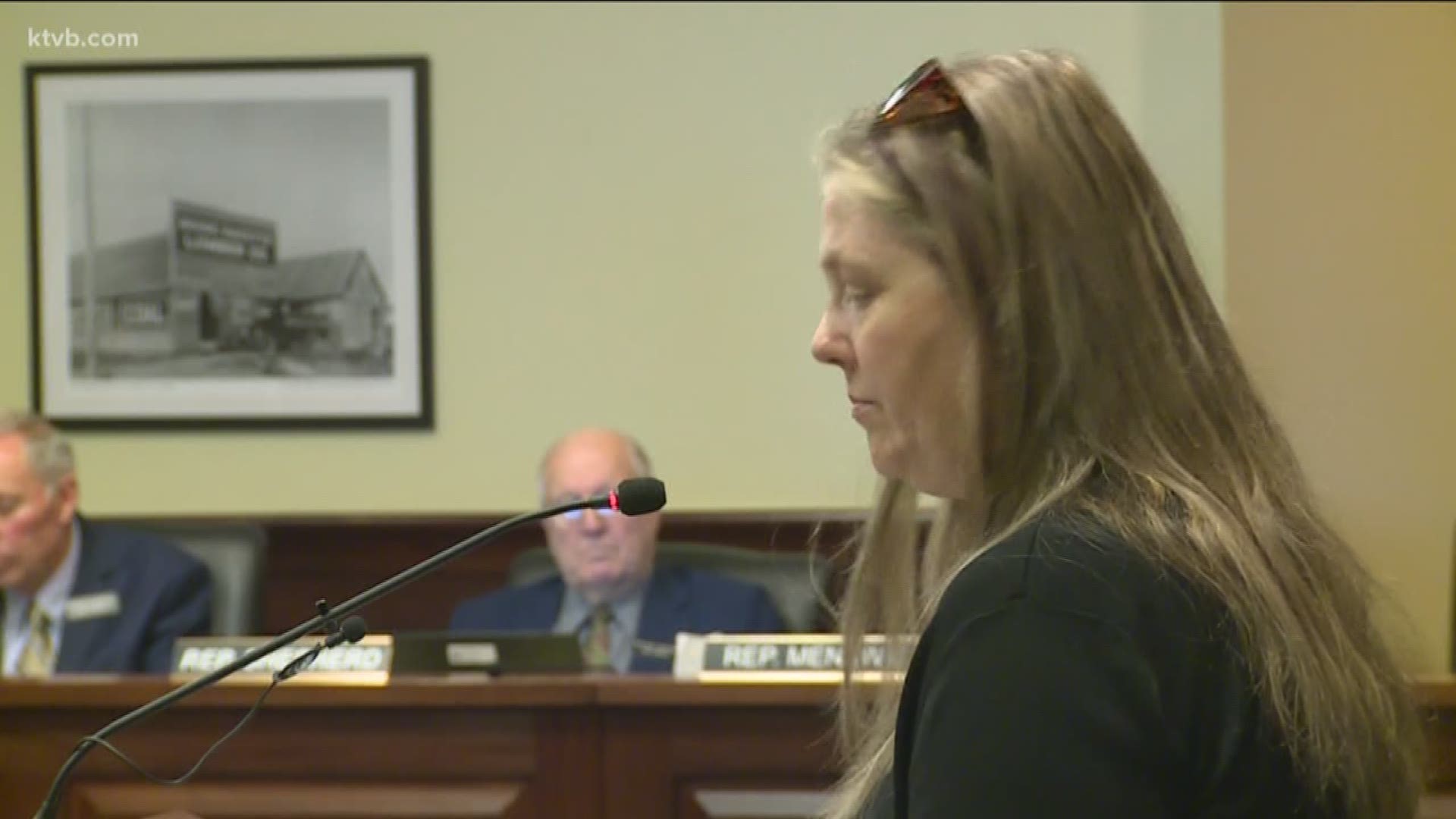

Melyssa Ferro, who was the 2016 Idaho Teacher of the Year and who co-chaired the committee that worked on the science standards, said they allow students to actually practice science instead of just memorizing facts.

"One of the strengths of the standards is it really allows teachers ... to look at the science from a state of evidence," Ferro said, "to talk to students about what's going on in their local communities and local issues."

She said the standards give teachers the flexibility to talk about how industries may mitigate effects on the environment, and other things relevant to their communities.

The standards were first adopted about 10 years ago as educators and lawmakers sought a way to consistently measure academic achievement among Idaho's students, which now number about 300,000.

The standards are part of the administrative rules put forward by the Idaho Department of Education. Typically, administrative rules pass without much debate, but lawmakers last year failed to pass a bill approving them, allowing all the state's administrative rules to expire.

As a result, all the rules are before the Legislature for approval this year, and some lawmakers are using the chance to try to get the Common Core-based standards stripped from the state's curriculum.

About 15 people testified in favor of keeping the standards as they are, including several teachers and science professionals. Ten people spoke against them.

High school physics teacher Eric Theis said the standards ensure that his students have the same base-level skill set when they arrive in his classroom. He said without that base, he would lose valuable teaching time getting everyone to the same level so they could start learning physics.

"When we talk about removing them or major portions of all of them wholesale," Theis said. "That throws our school system into chaos. It destroys alignment and it makes our students suffer."

Fred Birnbaum, vice president of the group Idaho Freedom Foundation, objected because the standards included information on climate change, saying "the science isn't settled."

"The science standards go beyond their mandate of science standards, it delves into curriculum and content," Birnbaum said. "It tells teachers what to teach and how to teach. That's not what the standards should do."

The vast majority of peer-reviewed studies, science organizations and climate scientists have found that the world is warming, mainly because of rising levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, and that most of the increase in temperature is human caused.