BOISE, Idaho — Growth can't be stopped altogether. The key is coming up with ways to manage it, and include as many citizens as possible in the planning process.

That's why Ada County commissioners have been holding neighborhood forums, including the one that took place Thursday evening at Castle Hills Church of the Nazarene, in northwest Boise's Collister neighborhood.

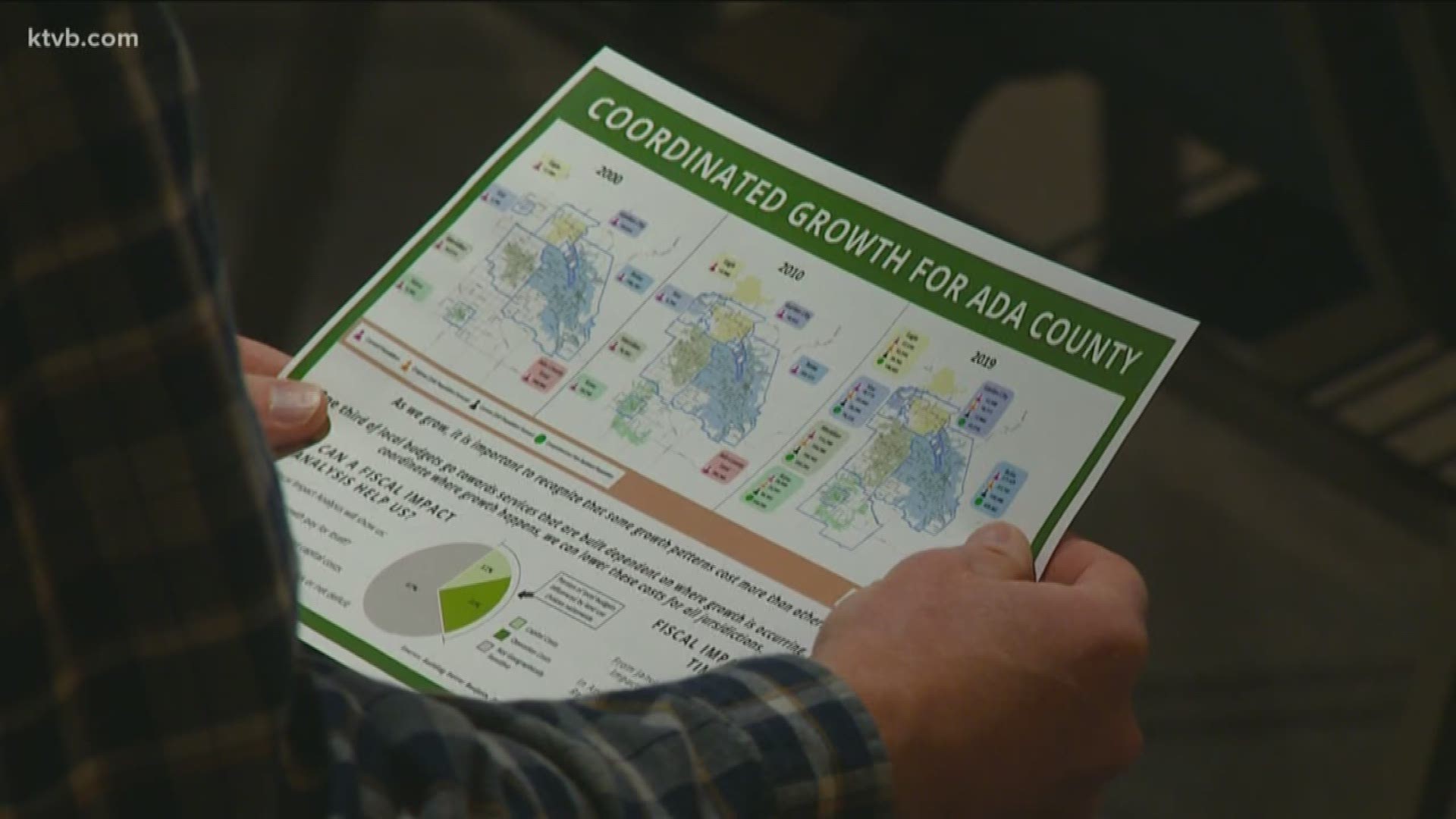

According to projections presented by the county, Ada County's population will reach 690,000 some time over the next 20 years. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates the population was already approaching 470,000 in 2018. In the 2010 census, the population was a little more than 392,000.

One resident who said he worked for many years as a state and county transportation engineer mentioned plans for more than 20,000 new homes in the foothills in north Ada County, and its potential impact on traffic, particularly on Idaho 55. He asked the commissioners what they planned to do about that.

"If that happens, Highway 55 will have to be upgraded to an interstate," he said. "It's going to cost $500 million to a billion dollars. We don't have the money. If we had the money, it would take about 20 years to acquire the right-of-way, have the public hearings ... design, and construction. We don't have 20 years. It's happening today. And if nothing is done, Highway 55 is going to be a long parking lot during peak hours. And I guess my question is, what are you going to do about it?"

Commissioner Kendra Kenyon was the first to respond, saying she believes Highway 55 is already being overused. Kenyon also said she's really "not a fan of planned communities" like Avimor and the Dry Creek Ranch development, which were approved under codes established more than a decade ago, and are located near Highway 55. One reason, she said, is a lack of retail and industrial businesses to support those neighborhoods.

"Since we came on, our staff has really looked closely at the planned community code, and it's very stringent right now," said Kenyon. "It's a two-pronged approach. You need to prove that financially you really could do all the things that need to happen when it comes to being a true planned community. And so far, we haven't had any (issues), even with the tremendous growth we have right now."

Kenyon and Diana Lachiondo, both Democrats, were elected to the Ada County commission in November 2018, and took office in January 2019.

"I share Commissioner Kenyon's view that I do not believe in general planned communities," Lachiondo said. "They tend to be 'leapfrog subdivisions' that have little access to retail, jobs, certainly public transportation. And this is playing out in real time, so because Ada County updated our code ... it comes back to the data ... Ultimately numbers don't lie, and we'll just have to see what that looks like."

Rick Visser, the Ada County commission's lone Republican, cited Dry Creek as an example of good planning.

"They have a commitment to open space; 70 percent of that development is open space," Visser said. "They have a state-of-the-art wastewater treatment system that returns water that is drinkable. It's not going to be drank because of the stigma about it, but the value of putting drinkable water back into the aquifer cannot be over-emphasized."

Two more neighborhood meetings are scheduled for March 5 in northwest Ada County and March 19 in southwest Ada County. The venues for those meetings have not yet been announced.

Whatever form growth in Ada County will take in the next 20 years, one question is constant: how to pay for it.

Idaho law mandates 80 percent of a county's services -- such as the sheriff's office, coroner's office, courts, and driver's licensing.

Consequently, counties have less discretion than cities in how to use the tax money they collect, the commissioners say. The county doesn't have the authority to tell cities or the Ada County Highway District where to set their taxes or how to spend those entities' revenue, so to keep Ada County's costs down, they say it's important for city and county governments to coordinate.

"We do coordinate. It's sort of like trying to put together a puzzle, without knowing what the puzzle should look like at the end of the day," Kenyon said. "And everyone has their own pieces and parts to the puzzle."

That's why Kenyon and Lachiondo have voiced criticism of proposals in the Idaho Legislature to impose tighter caps on - or freeze altogether - the amount of a property tax increase cities and counties can adopt each year.

Lachiondo called that a "sledgehammer approach."

"It's a more holistic conversation, I believe, than capping property taxes," she said.

Commissioner Rick Visser, the board's one Republican member, says he's had conversations with a lot of Ada County residents concerned about property tax increases. In a statement released on January 21, he said he proposes limiting county departments' base budgets to a two-percent increase over the current fiscal year's budget; also, freezing supplemental budget requests to zero increases, freezing all county expenditures to this year's levels, and not using any foregone taxes.

"People are struggling to actually stay in their homes," Visser said. "That's untenable."

Several hearings will take place before Ada County approves a budget for the 2021 fiscal year, which begins on October 1, 2020.

Kenyon said with the final budget adoption still several months away, "the larger conversation needs to happen for the bigger solutions to occur."

Watch more 'Growing Idaho':

See them all in our YouTube playlist: