BOISE, Idaho — If you've ever purchased a home in an older subdivision in the Treasure Valley, you may have noticed disturbing language in your homeowner paperwork.

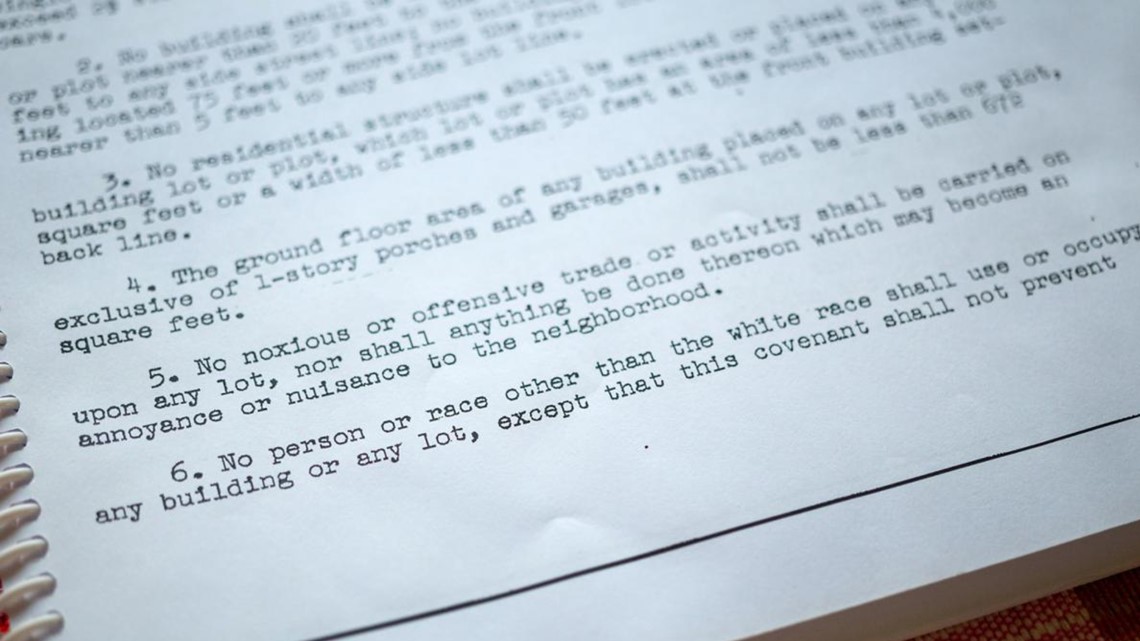

“No persons other than persons of the White race may reside on the property except domestic servants of the owner and tenant."

The Idaho Press reports that's an example of what homebuyers of older houses may encounter in their Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions document, or CC&R, according to Zoe Ann Olson, executive director of the Intermountain Fair Housing Council.

This racist language still exists in decades-old documents, more than 50 years after a 1948 United States Supreme Court decision to outlaw enforcement of housing covenants that denied people of color access to housing. The decision didn't ban the language itself, but rather enforcement of it.

Even now, there are few ways to remove the language, Olson said. Though the CC&Rs are unenforceable, such language still raises fear in communities of color, she said.

“When Realtors and people of color come to us, saying, ‘I can’t buy this house, because look at this language,' it raises this fear and harm all over again," Olson said. "And so people have to have some mechanism to address it."

In Shelley v. Kraemer in 1948, the Supreme Court found that the racist covenants could not be enforced. And in 1968, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act, that outlawed housing discrimination based on “race, color, religion, or national origin."

Brindee Collins, a property and real estate attorney and owner of Collins Law PLLC in Boise, said the Supreme Court decision and the Fair Housing Act make it impossible for anyone to enforce racially discriminatory covenants.

However, there are few ways to get the language removed.

Collins said some state legislatures have passed bills outlining procedures that allow a homeowners association board of directors to amend and remove a “problematic set of CC&Rs."

Idaho does not have such a procedure, so the process for removing the language becomes even more complicated. To do so, the HOA board must follow the rules for amendments cited in the document itself. Collins said in most circumstances, amendments require a supermajority of residents to approve it. In some neighborhoods, the HOA may have dissolved, so there's no board to oversee these issues.

“It is not that people like the provisions or that people want to keep them in there," Collins said. "It is usually just an apathy problem of getting 75% of the people to return a written ballot to amend it."

However, Collins said, “They have an obligation to try to amend it and, if not, they need to adopt a policy that explains that the provision is not enforceable. They have an obligation to try to amend it.”

HISTORY OF RACIST HOUSING DOCUMENTS

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision. The continued existence of the discriminatory language caught the eye of then-editor of Idaho Business Review, Anne Wallace Allen, who wrote in May 2018: "This language belongs more properly in a museum or exhibit that can be used to show the world how far we have come. Why shouldn’t Boise be the first community in the country to unite and remove the racist language?"

In a July 2018 blog post on the Boise Regional Realtors website, Olson wrote that the discriminatory language was sometimes required in housing documents through the mid-20th century by lenders and insurers participating in federal loan programs, and by city, county or state law.

Olson said the CC&Rs were also designed to reinforce the idea of “all white” neighborhoods. She said because of these practices, people of color were segregated into cities instead of being allowed to live in the suburbs where many of the covenants were enforced. She also said people of color struggled to obtain home loans because of the documents' language.

In Washington, a state law that took effect Jan. 1 allows anyone to file a request with the county auditor to strike discriminatory language from housing documents, according to The Seattle Times, which reported no fee or attorney would be required.

Olson wants to see something like that come to Idaho.

“People think Idaho is predominantly white and that we are not welcoming to people of color, and I think we need to address that,” Olson said. “People of color are welcomed in every subdivision, and without the covenant language, nothing would stand as a barrier to make them feel like they cannot buy a home.”

More from our partner Idaho Press: New Idaho Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force website launches

Watch more 'Growing Idaho':

See them all in our YouTube playlist: