Here's what the Treasure Valley can learn about light rails from Portland and Salt Lake City

Mass transportation systems took other cities years and hundreds of millions of dollars to build, and that might not be any different in the Treasure Valley.

Utah Transit Authority

It has been a decade since either the City of Boise or COMPASS, the planning association of southwest Idaho, started making plans to build some form of mass transportation in the Treasure Valley.

In the years since, the Treasure Valley's population has exploded and residents have made it clear at Boise City Council meetings that many of them want better public transportation in the region as the struggling bus system isn't keeping up with growth.

The City of Boise has discussed the possibility of building a streetcar or trolley in downtown Boise for over a decade now. In 2009, the city proposed a $60 million new trolley system that would connect downtown Boise and the Boise State University campus. In order to help pay for the project, the city applied for $40 million in federal grants. The city's seven applications all lost.

Since the city first announced a possible trolley system, the city has received federal funding to study transit options in 2012 and held public hearings on possible routes in 2014. In the last five years, few updates on the project have been revealed.

The City of Boise did reveal a possible route of the proposed circulator, connecting downtown Boise and the Boise State University campus. The route was limited to operating down 9th Street and Capitol Boulevard, and east and west along Idaho and Main streets

There aren't any new updates on the city's circulator proposal, according to City of Boise spokesperson Mike Journee. Journee said that they're only gathering information needed to apply for federal funding for the project and are in the early preliminary stages of the proposal.

The latest plans for a Treasure Valley-wide mass transit system was a 2009 COMPASS study that analyzed possible routes and corridors for different forms of mass transit.

However, neither Boise, Meridian, Nampa nor Caldwell have any currents plans to build a commuter rail through Ada and Canyon counties, according to each cities' spokesperson.

Nampa Mayor Debbie Kling said there is a need for more transit to be built but said the form of a new mass transit still needs to be decided.

"I think it has to be a collaborative effort and so it's all landing on that same decision - you've got to come to a consensus as a community on what that mode of transportation is," she said.

Without new plans for mass transit systems in the Treasure Valley, residents may not have a clear picture of how long such a project may take or how much it might cost taxpayers. The Treasure Valley has also grown significantly in just the past few years, which is prolonging travel times as main roadways are seeing more drivers than ever.

KTVB set out to learn what it could take to build a Treasure Valley-wide light rail system. To do this, we analyzed the creation of light rail systems in the Portland and Salt Lake City metro areas. Both systems extend outside city limits, connecting their whole metro areas, which could be similar to a Treasure Valley-wide rail system.

The El Paso Streetcar system was also analyzed since the project is limited to downtown El Paso, Texas, much like Boise Mayor Dave Bieter's circulator proposal.

Scroll down to see what transit leaders in Portland, Salt Lake City, and El Paso said about their systems and what Treasure Valley residents could expect.

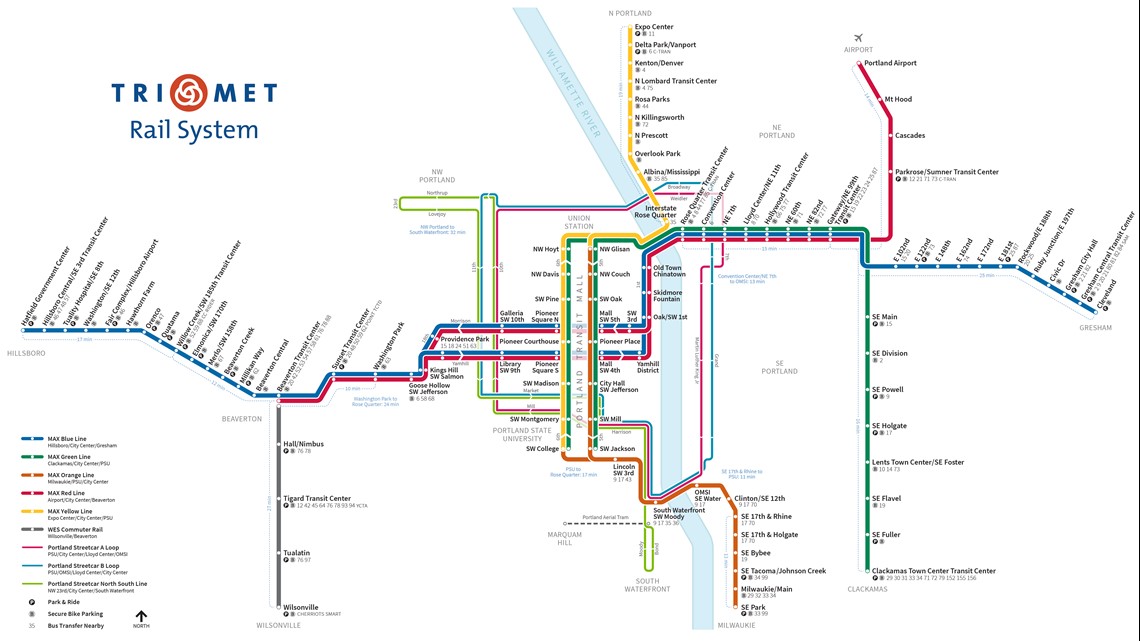

Portland's MAX Light Rail 40 years of planning and billions of dollars spent connecting the area

Portland made an early investment in light rail in the 1980s. The first line in Portland was built in 1986, becoming the third-ever light rail system in the country. TriMet, the agency that oversees the Portland metro area's transit systems, started with a 15-mile line from Portland to Gresham, Ore.

The first line in Portland's tram system took four years to build and cost about $214 million. Adjusting for inflation, it would cost just over $500 million in 2019.

In the 33 years since it opened, the MAX Light Rail in the Portland area has grown to over 60 miles of track and new lines have been added every few years. The MAX had additions in 1998, 2001, 2004, 2009 and was last expanded in 2015.

The total cost of the MAX Light Rail? $3.72 billion dollars.

Federal government agencies paid for 60% for the total costs for Portland's light rail system.

The massive investment from federal and local governments have been done in an effort to cut back on traffic and bring the Portland metro area closer together, according to Tia York, a spokesperson for TriMet, the agency that oversees the Portland metro area's public transportation services.

York said the MAX is built with Portland's vision of growth and development in mind.

"Transit connects people to opportunity and their community – whether they use it for work, school, a doctor’s visit or to get to a Blazers, Timbers or Thorns game," she said. "It also makes communities more vibrant and livable, by addressing congestion and helping reduce carbon emissions."

BELOW: Map of Trimet rail lines

The investment to get cars off the roads to reduce traffic and emissions seems to be working, as the MAX Light Rail averaged 121,100 boarding rides per weekday in the 2018 financial year.

"When congestion is reduced – freight can travel more freely and people spend less time in traffic, freeing up time to spend with family or do something enjoyable," York said. "Our transit system improves our region’s livability."

The transit system has also spurred new developments as businesses, restaurants and residences opened near the stations. TriMet claims that over $13.2 billion of development has been built in the vicinity of MAX lines since 1978, when the project was first approved.

"We have seen extensive development and redevelopment in station areas," York said.

Salt Lake City's TRAX system 89 miles of track built in 20 years

The Utah Transit Authority was solely a bus company for decades, but officials were ultimately able to plan ahead to become one of the largest transit authorities in the country by coverage area.

Salt Lake City's light rail system, TRAX, first opened in December 1999 and it was expanded in 2001, 2003, 2011 and 2013. The Max Light Rail system spans 42.5 miles and has 50 stations across its three lines.

However, TRAX, much like MAX, is part of an interwoven system of different mass transit systems that serve about 80% of Utah's population.

UTA built 89 miles of its commuter rail, Frontrunner, including a 44-mile stretch between Weber County and downtown Salt Lake City. The project for Frontrunner took three years to build after construction began in 2005, but much of the rail line was bought from Union Pacific in 2002.

A project like the Frontrunner commuter rail is something that UTA Executive Director Steve Meyer said could work in the Treasure Valley.

BELOW: Map of the UTA Rail, including TRAX and Frontrunner

Meyer, who is a Boise native, said that using a mixture of existing rail lines and building along Interstate 84 would offer an ideal corridor for a commuter rail line to connect Boise and Caldwell.

“You got an interesting rail line running through the county, paralleling I-84, that’s a tremendous asset," he said. "In my mind, it would operate more like a commuter rail than a light rail, because you got a long distance (between Boise and Caldwell)."

The cost to build the entirety of Frontrunner (which connects Salt Lake City north to Ogden and Provo to the south) and TRAX is about $3.41 billion. Federal funding for the projects was about $1.4 billion and local funding covered the other 59.4% of the projects.

Carl Arky, a spokesperson for the UTA, said the cost to build the system would only grow if they were to build it now.

"Not an inexpensive proposition and the costs would be greater if we were just starting to build all of this today," he said.

Arky said Boise needs to settle on a plan and move towards it, even if it means it changes how business is done in the area. He has a new incentive for it, too.

"I hope Boise upgrades its mass transit system now that I own two properties in Meridian," he said lightheartedly.

The UTA is funded in three main ways - local sales taxes, legislative funding, and fares. In Idaho, the state does not offer any funding for public transportation and municipalities and counties cannot institute local taxing options.

The lack of local funding would make building a mass transit system difficult as it already a struggle for Valley Regional Transit, the valley's bus service, to receive funding.

In the UTA's budget in 2018, the light rail's operation costs $48 million.

El Paso's Streetcar Using the streetcar system to spur economic development

Instead of a region-wide transit system, the City of El Paso opted to revive their streetcar system in their downtown area in 2012 and it opened in 2018.

The El Paso Streetcar is two loops of track, making a figure-eight shape, in the heart of downtown El Paso.

The city used to have a streetcar system from the 1950s to 1974. El Paso restored all of the original streetcars in 2015.

The system reopened in 2018 after about a year and a half of construction. The total cost of the project was only $97 million.

According to Jay Banasiak, the director of Sun Metro, the agency that oversees transportation in El Paso, the city's streetcar was completely funded by the Texas Department of Transportation.

The City of El Paso and Sun Metro did pay $5 million to conduct a feasibility study on the project before construction began.

While the state of Texas did pay for the project, they don't fund the operations of the streetcar. Banasiak said the city's sales tax of .5%, federal funding, fares and revenue from advertising for operating costs.

For Sun Metro, officials planned the streetcar knowing that systems like theirs are typically built as economic drivers first and public transit second. Banasiak said El Paso has had several years of strong economic growth leading up to streetcar's operation and the service has complimented that development, with new construction and businesses popping up around some of the stations.

BELOW: Map of the El Paso Streetcar

"We’ve had several hotels that have been rebuilt, remodeled. We’ve had a new hotel that was built, the Marriot Courtyard was just built," Banasiak said. "During this time, we’ve had the (Triple-A minor league) baseball Chihuahuas, which were just starting then, and the (El Paso) Locomotives now, this is our first year of professional soccer. So we think that (the streetcar) might have played a little bit of a role in downtown."

Banasiak said before Boise and the rest of the Treasure Valley can begin planning on building a streetcar system, the city needs to start analyzing how this type of system could be best used in the area and if building a streetcar system could drive growth in certain areas.

"The first thing is look at your system and see whether you can come up with a route that hits pretty much everything," Banasiak said. "The second thing you probably need to look at is on the transit end of it - that would be on the economic end of it, the planning end of it - are there areas of Boise that can be revitalized because of it? Specifically, that you got long stretches of blocks that, 'Man, if we put something in here, would restaurants come and would small apartments start being created?' Those are the kinds of things you gotta think about before you even wanna think about a streetcar system."

In comparison, Boise's proposed circulator route is far from the city's newest urban renewal districts that the city wants to drive economic development toward.

What the Treasure Valley can learn from these projects Funding will be needed before any projects can move forward

Meyers, Arky, and York all agree that if the Treasure Valley wants a mass transit system built, everyone from the community, statehouse, and the federal government need to be on board with it.

"Strong leadership from a regional governing body and jurisdictional partnerships are critical," York said. "You need support at the local, regional, state and federal levels."

Finding common ground on a solution between everyone that is involved with mass transit is one of the biggest hurdles for TriMet, York said.

Arky with the Utah Transit Authority also said building mass transit requires the general public and the state legislature to buy into the plan of building mass transit and building a transit system takes years to build out in stages.

York agrees and said that building a light rail system won't happen quickly.

"It takes years and sometimes decades for a light rail line to come fruition. You’ve got to have the time to do it and do it right," York said.

Nampa Mayor Debbie Kling agrees that building mass transportation will need to be a collaborative effort and it won't be built anytime soon.

She also said that if any form of mass transportation being built within the next decade would be surprising.

"In reality, it will be ten years - I would think - before we have something up and running," Kling added.

Banasiak explains that before any building can happen, the City of Boise needs to conduct a feasibility study, plan routes around major hubs and see how the system can revitalize parts of the city.

"I think doing a feasibility study, looking at the routing, getting everyone involved on it, get the pricing of it, have them look at how to fund it, how to operate it, would definitely be worth you’re while if you’re serious about doing that," he said. "And you can add to it, the feasibility study, what’s the economic value of it."

WATCH BELOW: Is Treasure Valley traffic really that much worse than it was a few years ago?

The biggest challenge to building mass transit in the valley may be funding, according to Meyer. All three transit systems in El Paso, Portland, and Salt Lake City rely on federal funding and local taxes, like payroll or sales taxes - something that isn't available in Idaho.

Meyer said until there's a dedicated funding source for public transportation in Idaho, any transit system wouldn't be able to receive federal funding since it's missing long term funding needs.

“The biggest challenge that I see for Ada County and Canyon County (is funding), you're a metropolitan area in a very rural state, and people need to be thinking that you’re a metropolitan area with metropolitan problems and challenges, and you gotta get a dedicated funding source," Meyer said.

In the next 20 years, the Treasure Valley is expected to grow to a total population of over 1 million people. With recent population growth and economic development, the Treasure Valley's roadways are already being strained and drive times are expected to become longer.

Mayor Kling also sees the lack of any funding as the main hurdle for a light rail, commuter rail, streetcar, or any form of mass transit to be built in the Treasure Valley.

"I think funding is the thing that has paused us. The pause for all these years and tremendous discussion and work has been done, but the hindrance has been funding," she said.

Watch more 'Growing Idaho':

See them all in our YouTube playlist: