BOISE, Idaho — As of mid-January, the state of Idaho has sequenced nearly 5,000 COVID-19 positive samples to find circulating variants. As positivity rates rise across the gem state, so does the need for sequencing.

“We are processing thousands of samples a week, we have completely built a new sequencing program from scratch," said Doctor Christopher Ball, the Lab Director for the Idaho Bureau of Laboratories.

According to Dr. Ball, 98 percent of the samples sequenced are Omicron positive. Whole-Genome Sequencing is nothing new to the lab. He said the state has been doing sequencing for things like bacteria viruses that cause food-borne illnesses for several years. Before COVID, the lab was processing 16 samples every two weeks, which use to be their capacity.

"If you would have asked me three years ago that I am where I am right now, I would not believe it," said Technical Supervisor for Genomic Sequencing Aimee Ceniseros.

Through federal funding, the lab has been able to build its program and acquire new resources in order to meet demand.

“The goal here is to really try to monitor how the virus is changing through time and to be on the lookout for new variants of concern,” Dr. Ball said.

The lab can begin processing around 300 samples a day, but the process can take days and includes various steps.

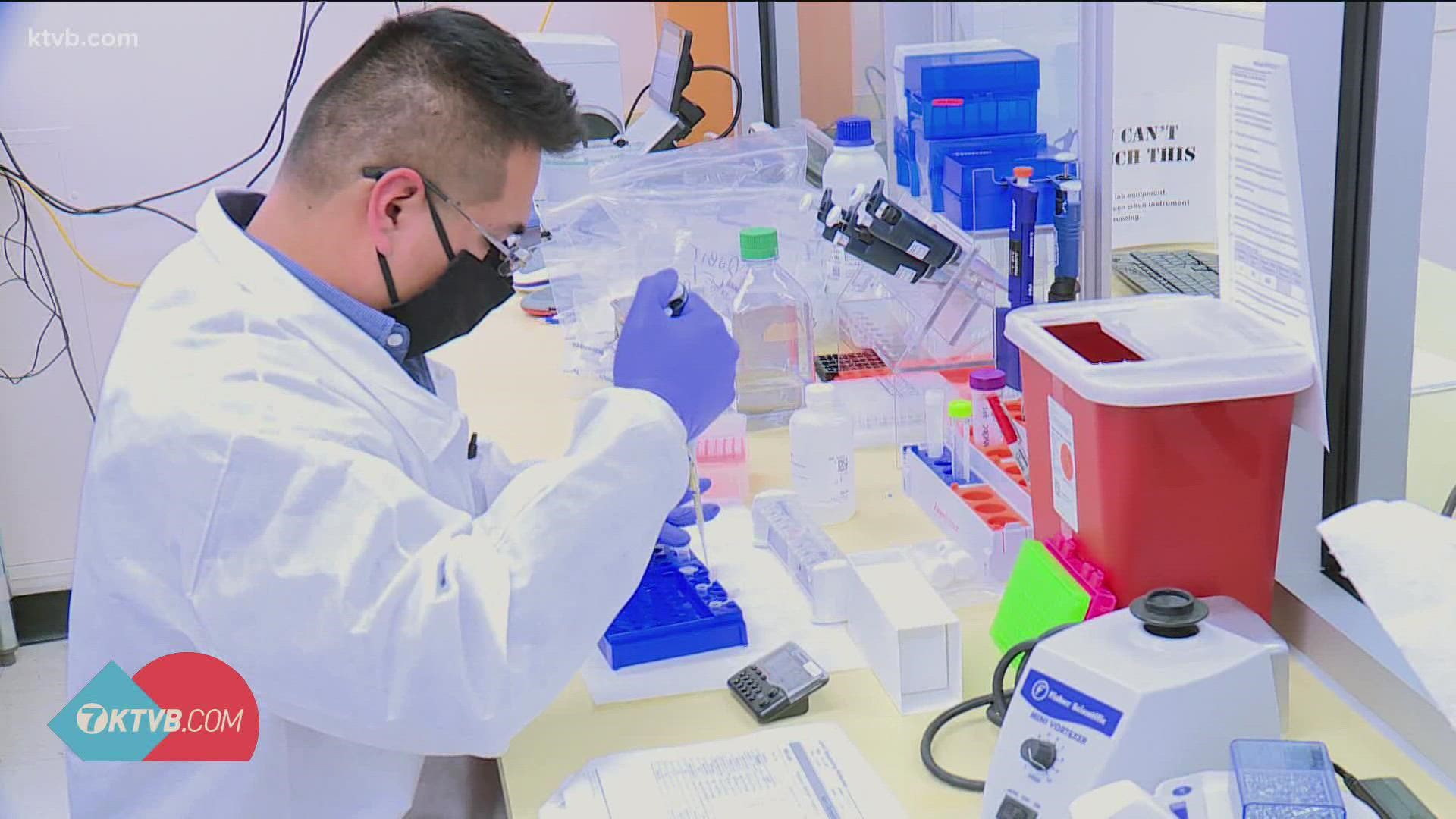

The Idaho Bureau of Laboratories has positive samples sent to them from labs throughout the state. Once the samples are collected, they are prepared for extraction of the nucleic acid. Which means chemicals are put together so they can purify or clean a positive sample.

"We take the sample that has the virus in it and we separate all the DNA and the RNA in that sample from everything else," Dr. Ball said.

According to Dr. Ball, the DNA and RNA are separated in order to create a high concentration of it and to get rid of any enzymes in the sample that could potentially create a false negative test.

The chemicals are put into 94 individual tubes, which is the amount that can be processed at once. Then the chemical solution is added to positive samples, a step that must be done by hand.

"Our staff have to be really focused because you have got 94 patient samples into a precise location and you have got to make sure you are matching the sample so we get the right patient associated with the right sequence,” Dr. Ball said.

The samples are then placed into an extraction machine that uses a magnetic method to separate the RNA from the DNA in each positive sample. After that, thousands of copies are made of a single sample.

"So that's what we are doing here in this instrument and it goes through a bunch on temperature periods that help the chemicals in there make all those copies of the genetic material," he said.

After copies are made, each sample is given a barcode in order for lab workers to be able to identify each sample and where it came from. After the barcoding, the samples are placed in one tube and loaded onto a sequencer. The sequencer takes 16-24 hours to complete, once completed it makes a digital copy of each sample. That data is then transferred to a computer where sequences are compared to other databases to decipher what variant is present.

“It’s almost exclusively Omicron with a few Delta mixed in,” Dr. Ball said.

Once the variant is determined, the sequence information is submitted to the state to report.

"I understand why people, they want to know the answer quickly and I think that it’s a misconception that it’s an easy answer to get to, that we can just take the sample, put it in an instrument and it's going to give us the answer in short order," Dr. Ball said.

"It’s really been a challenge to balance workload and expectations to make sure that these hard-working state employees can continue the hard work they have been doing for two years and now going onto the third year," he said.

"Two years into it, it's very frustrating, a lot of people reference it like running a marathon, but we are at the point of when does the marathon actually end," Ceniseros said.

Facts not fear: More on coronavirus

See our latest updates in our YouTube playlist: