BOISE, Idaho — This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press.

From hearing some Idaho officials discuss the fentanyl crisis in the state, those with poor geography skills may think the Gem State borders Mexico.

Although the border is more than 900 miles away, when it comes to fentanyl distribution in Idaho, Mexico does play a huge role — but not always in the way it’s depicted.

Earlier this month, Idaho Gov. Brad Little traveled to the Texas southern border to attend a security briefing in which he and other governors received intelligence about illegal immigration in relation to the potent deadly drug.

Little also announced in May he would send two teams of Idaho State Police to Texas to train with the Texas Department of Public Safety on cross-border smuggling, human trafficking, and drug interdiction, and that they will return to train other law enforcement agencies in Idaho.

He and other top politicians in the state have repeatedly said that the growing fentanyl problem in the state is being fueled by Mexican drug cartel activity.

Essentially all of the fentanyl trafficked in the U.S. is made in Mexico, said Matt Gomm, Drug Enforcement Agency special agent in charge. He said U.S. law enforcement intelligence has found that most of the precursor chemicals come from factories in China and are shipped to Mexico to be made into fentanyl and then distributed.

“When it gets to Mexico, they have super labs all throughout the country, and they make a lot of fentanyl,” Gomm said. “I mean, millions and millions of pills.”

The U.S. regulations are tight enough that the precursor chemicals in the bulk amounts used by the cartels can’t usually get shipped straight to the states, so they go south. Some of the chemicals also originate in India.

However, for the most part, it’s not coming into the U.S. as part of illegal crossings, Gomm said.

“Many are coming through ports of entry in vehicles with hidden compartments,” he said. “The cartels recruit people to drive them across the border through the ports, not walking through the desert.”

NPR reported in March that the drug is smuggled through official ports in around 70 million cars and trucks every year. However, many Americans incorrectly assume the drugs are being smuggled by migrants, an NPR/Ipsos poll found last year.

Experts say that some cartels may be using the chaos of increased border crossings as a distraction, but the migrants themselves are typically turning themselves over to seek asylum and aren’t carrying illegal drugs.

U.S. Attorney for Idaho Josh Hurwit said he’s not aware of any fentanyl seized in the state that originated from anywhere but the U.S.’s southern neighbor. However, it doesn’t necessarily follow a direct line to the Gem State from the border, he said.

There are differing levels of removal from the cartels themselves, he said.

The drugs typically follow the interstates, he said. In North Idaho, the supply may be coming in from Washington, it might get to Twin Falls via Nevada, and sometimes traffickers are caught passing through Idaho on their way to Montana, where they can often get a higher price, Hurwit said.

“The more remote you get, North Dakota for example, you can get even higher prices than Montana or Idaho,” he said. “... sometimes it’s someone driving 12 hours from California, or near the border, or sometimes it’s a dealer in Spokane or somewhere in Reno, and then it gets here after a couple stops.”

When drugs are seized, and traffickers are arrested, investigators work to find the origins and determine the extent of the operation, Gomm said.

“We try to get the biggest players in these cartels involved in these conspiracies,” he said. “So when we do get an arrest on the street, we do try and follow it back to who supplied, where it came from, all the way up the chain to the person that manufactured it.”

He said it’s common that one seizure will result in the eventual arrest of several dozen people.

A major example of this was the 2022 arrest of Nampa resident Wathana Insixiengmay for possession with intent to distribute 15 pounds of fentanyl. In March, she was sentenced to prison after it was determined she was a main distributor for a large drug trafficking organization. This was likely the largest individual seizure of fentanyl in Idaho’s history, according to a DEA press release.

There’s no doubt the issue is intensifying.

Gomm said that, not long ago, a drug seizure of fentanyl might total a pound or two of the drug. Now, it can be in excess of 10 pounds, he said. Hurwit and Gomm both said that it’s more common for pure fentanyl powder to be seized, rather than pills.

“I think we’re at a different point in the opioid epidemic,” Hurwit said. ”Whereas before you had prescription pills, then you had people sort of being confused, and not purposely taking fentanyl when they were using those pills. Now there’s no longer much confusion in the drug marketplace. People are seeking fentanyl. People are selling fentanyl on purpose.”

Hurwit said for the first time in the state’s history, fentanyl convictions surpassed meth convictions, although many of these convictions involved both drugs.

In 2021, synthetic opioids were involved in 44% of all overdose deaths in Idaho, which is double the rate from the year prior, according to fentanyltakesall.org. Idaho launched the information campaign Fentanyl Takes All to spread education about the dangers of the drug. Little’s office said this month that it will soon announce the effectiveness of the campaign.

Last year, Little created “Operation Esto Perpetua” with the aim of reducing the flow of fentanyl and meth in Idaho. The operation has included the formation of a Citizens Action Group and Law Enforcement Panel to create a report on the issue and make recommendations on actions the state can take.

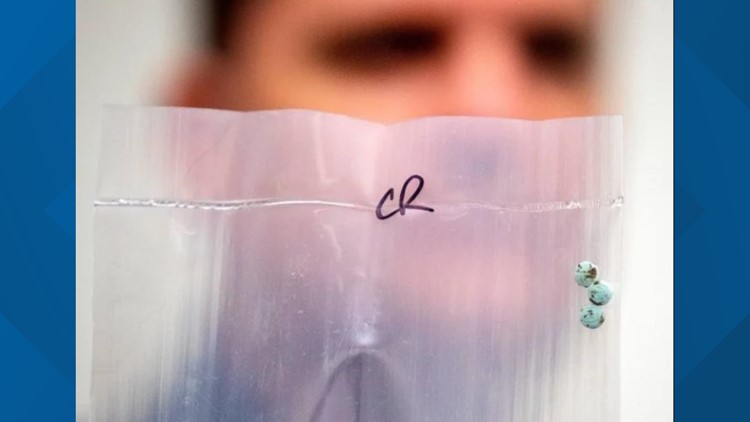

Around 2 milligrams of fentanyl can be lethal, and its danger often lies in its ability to be laced into other substances without the user knowing. In February, an Idaho Falls arrest seized 2,000 fentanyl pills disguised as oxycodone, the Post Register reported.

Gomm said it’s hard to determine if demand is increasing, but there’s certainly enough customers that trafficking is increasingly profitable. Hurwit said the fentanyl trade value in Idaho is in the millions of dollars.

“The economics of it are not in our favor,” Hurtwit said.

Gomm recommends vigilance when it comes to avoiding accidental overdoses.

“Don’t take any pill that’s given to you that isn’t certainly made in a pharmacy setting because you never know what you’re going to get,” he said. “... Be certain of what you’re taking, that’s one word we want to get out there.”

This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press, read more on IdahoPress.com.

Watch more Local News:

See the latest news from around the Treasure Valley and the Gem State in our YouTube playlist:

HERE ARE MORE WAYS TO GET NEWS FROM KTVB:

Download the KTVB News Mobile App

Apple iOS: Click here to download

Google Play: Click here to download

Stream Live for FREE on ROKU: Add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching 'KTVB'.

Stream Live for FREE on FIRE TV: Search ‘KTVB’ and click ‘Get’ to download.