NAMPA, Idaho — This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press.

As cars back up into the intersection, vehicles come to a full stop, with a horn sounding in the distance; it’s a railroad crossing.

Nampa’s trains have been around forever, or at least as long as the city has been established since the late 1800s. A remnant of Nampa’s heyday is the Nampa Train Depot, located off Front Street downtown and managed by the Canyon County Historical Society as a nonprofit.

The building is known for its one-of-a-kind architecture, with red brickwork and arched window frames designed by architect Frederick Clarke. The depot showcases a unique mix of architectural styles.

Historical Society President Aldis Garsvo described the depot as the birthplace of the city, with its rails connecting and bringing people to Nampa.

“For those folks, it’s like the internet is to us today,” Garsvo said.

As a landlocked area, Union Pacific wanted to connect its Oregon shortline to the Pacific Ocean to match up with the competition.

Contrary to the image of Western settlers, Garsvo explained the railroad expanded out first; then the travelers followed.

In turn, city growth also centered around rails.

“It’s not taking a true north direction,” Garsvo said, describing the setup of the rails.

Nampa’s streets run perpendicular to the railroads, as do many cities’ streets. But Nampa’s railroads present an awkward directional challenge, Garsvo said.

Rather than a direct north to south, the rails go northwest to southeast, meaning the roads in the heart of Nampa go northeast to southwest. This odd angle is visible on maps of the city.

Garsvo noted that railroads don’t cost taxpayers, as they are funded by the companies.

Nampa’s railroad connects to Portland’s seaport, bringing items originally delivered seaside by boats to the southwestern Idaho city. All sorts of commodities come through Nampa by train, Garsvo said, as similarly throughout its history.

“We have the best freight system in the United States, but the worst passenger system in the United States,” Garsvo said.

Recently, Treasure Valley leaders moved to bring passenger trains back to Idaho, but the state was not approved to receive federal funds, according to BoiseDev.

Nowadays, Garsvo said trains have gotten longer, often around a mile long.

“Train travel is vital,” Grasvo said.

Ed Dickens, manager of heritage operations at Union Pacific, oversees modern-day trains.

“Every single thing in our lives, every material, clothing, food ... all of that is carried in one form or another on the railroad,” Dickens said.

An average train weighs just under 10,000 pounds. Compared to semi-truck deliveries, Dickens said trains are more efficient. One flat car can carry the equivalent of four trucks. An entire train can carry as much cargo as 100 semis, Dickens said.

“It’s a critical part of America’s supply chain,” Dickens said, “with the ability to carry these bulk commodities efficiently and very quickly.”

In the 1940s, trains were updated with computer tech and, over time, steam locomotives were replaced by diesel.

While trains function efficiently in the background, they remain relevant to this day.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth,” Dickens said about the perception that trains are outdated.

Union Pacific lists Nampa, along with Pocatello, as important Idaho terminals.

“The area is laced with a network of railroad feeder lines serving Idaho’s richly varied agricultural industry,” the company’s website says.

Locally produced potatoes, sugar beets, beans, grain, fertilizer, phosphate and forest products are all moved by rail.

The Boise Valley Railroad, a Watco Company short line, consists of 36 miles of track. The Boise Cut-off consists of 25 miles of rail, running from Nampa to just southeast of Boise.

“The major population centers as we know them today owe their original history to railroading,” Dickens said.

In the 1970s, Union Pacific planned to demolish the Nampa depot, as it was no longer in use. Citizens at the time convinced the company to donate the building instead, forming the Canyon County Historical Society.

The depot has served as a museum since 1976 and still functions as a headquarters for the historical society.

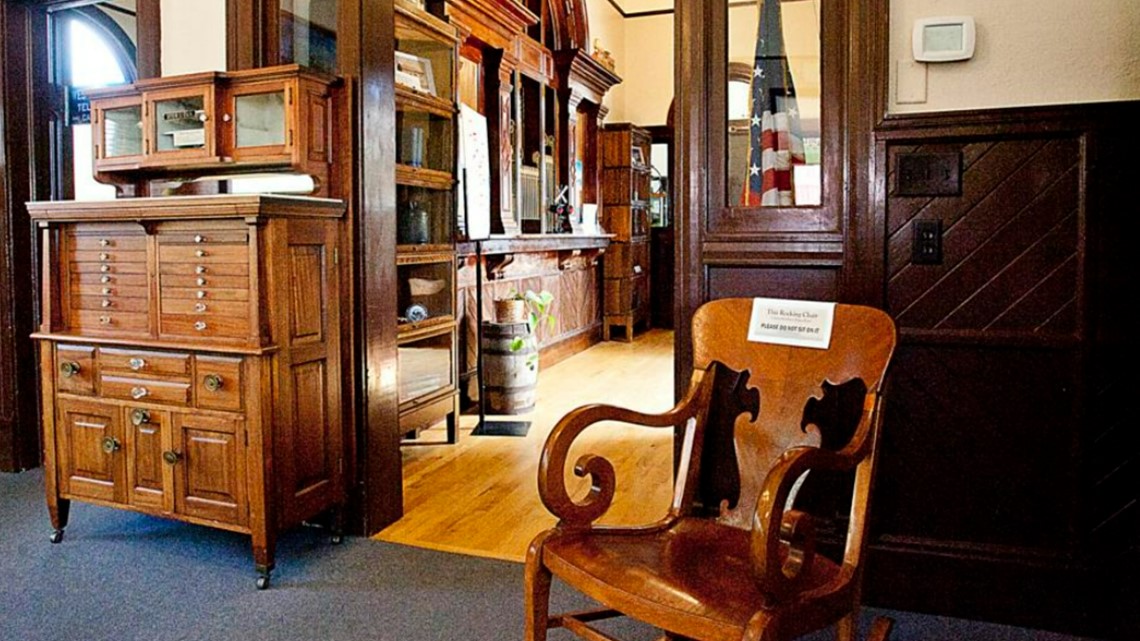

Entering the train depot today, on the right is a modern-day gift shop that used to be the men’s waiting room. Men and women used to sit separately, Garsvo explained, with two different waiting rooms and separate carts in the train. Oftentimes the women’s accommodations were nicer as well.

On the other side of the depot, the women’s waiting room holds antiques in glass cases, serving as an event room.

Run by the historical society, the train depot is kept afloat by a staff of volunteers and donations. Garsvo estimated that maintaining the depot costs $25,000 annually.

“To maintain a building that’s 120 years old, it gets real expensive real quick,” Garsvo said. “It’s still a challenge to keep the doors open.”

The depot is currently home to a digital archiving project, as well as physical glass plate negatives and historical books. The team of volunteers running the historical society works to keep these records of Canyon County’s history.

“If you don’t understand it, you can place no value in it,” he said.

The depot is open on Tuesdays and Fridays from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., and Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. Admission is free, but the society recommends donations of $5 per adult. More information about the depot can be found at canyoncountyhistory.org.

This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press, read more on IdahoPress.com.

Watch more Local News:

See the latest news from around the Treasure Valley and the Gem State in our YouTube playlist:

HERE ARE MORE WAYS TO GET NEWS FROM KTVB:

Download the KTVB News Mobile App

Apple iOS: Click here to download

Google Play: Click here to download

Watch news reports for FREE on YouTube: KTVB YouTube channel

Stream Live for FREE on ROKU: Add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching 'KTVB'.

Stream Live for FREE on FIRE TV: Search ‘KTVB’ and click ‘Get’ to download.