BOISE, Idaho — This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press.

It’s a warm Tuesday night in August as “Bullitt” Bob Denton speeds down the road looking like the peak image of retired living. He parks his shiny silver Porsche Boxster outside his airplane hangar in Nampa, opens the garage and pulls one Porsche right behind another.

Denton, his two pals and a guest mosey to the back room of his hangar — a 500-or-so-square-foot man cave with black-and-white-checkered tiles and about a thousand framed skydiving photos covering nearly every inch of wall space.

The host passes out cans of Rolling Rock and begins sharing the stories behind all the aviation-themed photos hanging up. He makes his way to the corner of the room and grabs a few discs by the TV.

“Oh, you did get it?” says Mike Bouton, a longtime friend and fellow skydiving buddy.

“Yeah, those are the two,” Denton responds, looking at his guest. “Have you seen it yet? Oh, this will be great for you.”

Denton, the 82-year-old who matches his grandkids’ zest for life, pops in the DVD and hits play. It’s a KTVB newscast from 1989 about their old friend’s funeral, a time capsule of sorts that shows how little the world has changed.

“Some new moves in the battle to fight higher gas prices,” the newsman says two minutes into the broadcast.

Denton scoffs. “Still fighting the same (expletive),” he hollers.

An airplane hangar neighbor named Tim strolls into the room, wondering why a bunch of dudes have huddled to watch a newscast from the first Bush administration.

“What is this?” Tim asks.

Denton responds: “It’s about our buddy Wally Benton.”

Mike Bouton was standing near the end zone, his head tilted up, when Wally Benton crashed into the Earth like a meteor.

It was Sept. 11, 1970. Bouton was a sophomore at Boise State. And his on-campus skydiving club was supposed to be having its finest moment.

For the inaugural game at the newly opened Bronco Stadium, the club convinced school officials to let them parachute in the official game ball. It was an opportunity for notoriety and exposure, a chance for the club’s more-experienced members to show off in front of a packed house.

So, just before kickoff, a Cessna 180 Taildragger cruised over the stadium. Its side door slid open. And four Boise State students jumped from 5,000 feet in the sky.

Wally leapt first, the inaugural game’s pigskin taped to the right side of his orange jumpsuit.

A burly, bearded Army veteran who was 27 at the time, Wally was a cocksure skydiver, having founded the club a year prior by telling the nine attendees of its first-ever meeting, “You guys are the luckiest ones on campus.”

With “an ego the size of the stadium,” as Bouton recalled with a laugh, Wally lived his life in hyperbole — a character and a showman who “could sell icebergs to Eskimos,” Denton said.

So naturally, it was not Wally’s intention to simply land on the then-green turf of Bronco Stadium. Ha. Anyone could do that. He was going to land right on the 50-yard line. Determined to land on the 50-yard line. He told that to anyone who would listen — and, by Wally’s standards, that wasn’t all that crazy.

Less than four months before the big jump, Wally placed first in an 11-team collegiate skydiving meet in Oregon. Twice he parachuted from 7,500 feet and twice he landed directly on a Coke cup lid that measured 3 inches across. This wasn’t some amateur.

He also planned to make the jump in style. He had gotten a Ram Air square-shaped parachute, a fairly new innovation from the days of almost-unsteerable round canopies that were the norm for skydivers from the beginning of World War II until the early 1970s.

The new chutes had increased steerability and performed much better into the wind. Plus, they were faster and, heck, looked much cooler. The only downside: Wally had only been using it for a couple months.

But things were going well when he dropped into the Boise sky just before 8 p.m. on that Friday night. Wally freefell for a few seconds then pulled his chute. It opened perfectly. He began floating down to the field. Just as he planned, he flew past the lights and readied to bank a turn into the middle of the stadium.

He attempted a maneuver he’d made a few hundred times — well, a few hundred times with a round parachute. But, because of the long parachute lines, this square-shaped canopy didn’t have the same stabilization on sharp turns.

As Wally went to shift himself to the 50-yard line, the chute went sideways on him. His body became a pendulum. As the canopy dove down, Wally shot up overtop it. Then as the parachute leveled out, swinging upright, its passenger slingshotted underneath it.

Wally was about 100 feet from the ground when he lost control.

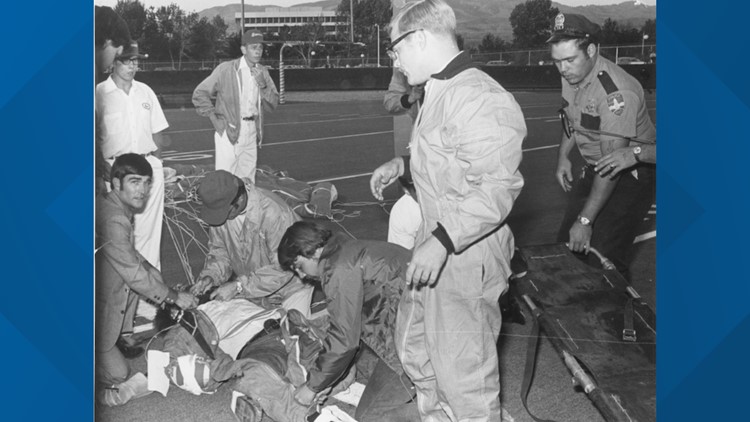

He fell like a rock, his body thudding into the hard turf and bouncing a few yards as screams echoed through the stadium. His femurs exploded on impact. His head slammed against the ground. His body lay motionless as the skydiving club raced over.

Among the first to reach Wally was the club’s faculty advisor, Bill Jones, who saw Wally wasn’t breathing. Jones gave him two breaths of air and Wally regained consciousness. Around that time, the three other skydivers — Larry “Whimpy” Homstad, Gary Gray and Tom Sullivan — landed safely, not knowing what had transpired.

“(His left leg) was up underneath him,” Bouton recalled. “The femur was sticking out. It just looked like his whole leg had broken off.”

“He said to me,” Bouton added, “‘bring the rest of my leg to the hospital to see if they can reattach it.’”

With the game ball lying beside Wally as he screamed in agony, his fellow BSC skydivers and medical personnel unzipped his jumpsuit and put him onto a stretcher. An orange-and-white ambulance, with its single siren whirring, zipped onto the turf, loaded Wally up and transported him to Saint Alphonsus hospital.

The first game at Bronco Stadium, a five-touchdown win over Chico State, had to be delayed about an hour. A crew came out, scouring over the field for bone fragments. Years later, when Boise State replaced the green turf, people were still finding pieces of Wally Benton.

Fifteen months after the crash, Boise State and Chico State played again. The Chico State fans who had traveled to Boise the year prior weren’t concerned with the scouting report on the Broncos; they needed to know what happened to that skydiver.

“I could not believe how many times people asked me how he was doing,” said Jim Faucher, Boise State’s former sports information director. “Some people thought he had died.”

It is hard to watch the video — to see Wally’s legs hit the ground at freeway speeds, his body thud and skid over the turf — and think he survived. Imagine someone scaling the light tower at Albertsons Stadium and jumping straight down. It seems inconceivable they’d live to tell the tale.

Wally barely did.

When he arrived at Saint Alphonsus hospital that night in 1970, with Bouton and other club members rushing over to join him, doctors were able to quickly stabilize his vitals. Then Bouton remembers the doctors saying, “Well, we think we can save him, but we’re going to have to amputate his legs.” Bouton fainted. The shock finally hit him. When he awoke, doctors told him they’d be able to save Wally’s legs, but a long recovery was ahead.

Wally was not a guy who crashed. He was too confident, too braggadocios — a strong-willed kid who loved skydiving more than almost anything else.

He was an extrovert with a boisterous personality that wasn’t exactly conducive to isolation. And suddenly, he lay confined to a hospital room bed.

It took him more than a year to leave Saint Alphonsus. One hellish year. He had his gallbladder removed. Doctors performed four major operations on his lower half. The worst of it were the skin grafts, when doctors transplanted healthy skin from other parts of his body and stuck it on his ravaged legs, leaving brutal scars that would forever remind him of the procedure.

Still, Wally was a beacon for the skydiving community, the fallen soldier who was not the least bit disillusioned with the sport.

When in the wake of his accident there were calls to defund the school skydiving club, Wally was the first one to speak up, encouraging more backing for the team after it took first place in the 1971 National Collegiate Parachute Championship.

When a newspaper reporter spoke with Wally a month into his recovery, he itched for redemption, even with his legs still shattered and several surgeries ahead.

“I have to talk a lot to myself to convince myself that I am making progress and the pain is something I can live with while the healing takes place,” he told the Idaho Statesman. “If my legs were healed, and if there was another jump to dedicate the stadium, I’d be happy to do it. And I’d hope for better results the next time.”

The day he was released from Saint Alphonsus, Wally knew exactly where he wanted to go. He called all of his friends to meet him. Just minutes after he got out of the hospital, 15 or so watched as Wally went onto the turf of Bronco Stadium.

This time, he was standing upright.

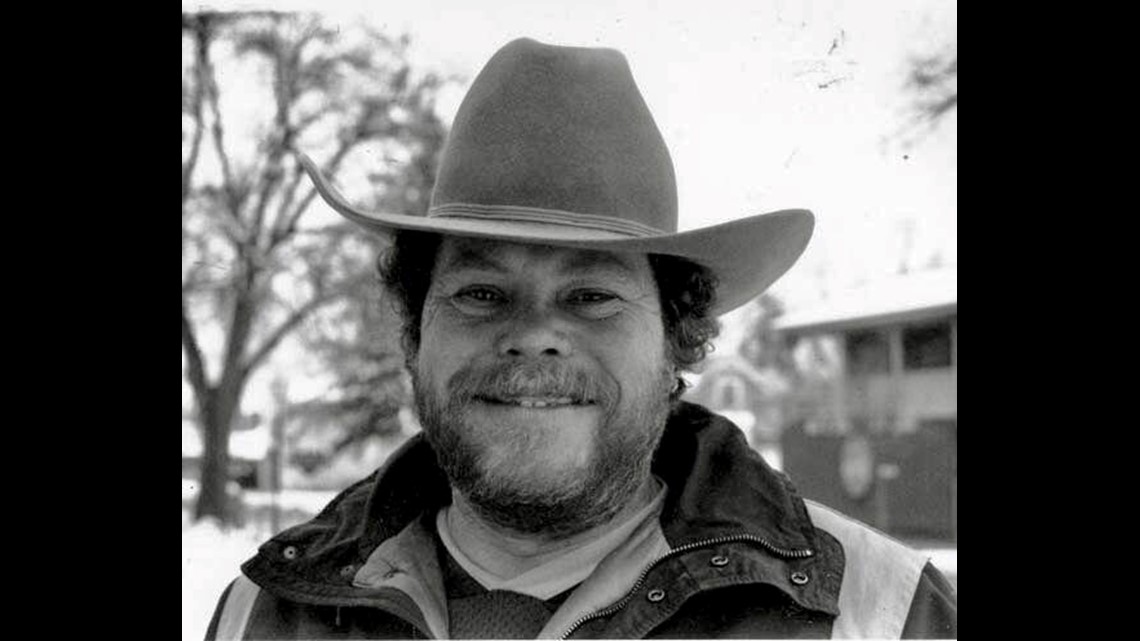

In the shadow of a green, 1950s-style Porsche sitting in Denton’s hangar, hangs a picture of Wally.

The black-and-white photo only shows Wally from his shoulders up. He’s staring at the camera with a soft grin. His beard is short but rugged, untrimmed and extending down his neck. His dark hair is long and curly, but tough to see under a big cowboy hat.

And then there are the eyes. They are dark and subdued, surrounded by bags and wrinkles and pain.

Denton and Bouton and another friend, Jim “Funny” Miller, aren’t sure where it was taken. Maybe at his grandparents’ ranch, they think. But they are sure of one thing: It was taken after his accident. It had to be.

“That’s after because he’s too damn fat,” Denton said. “He got heavy.”

For years after he left Saint Alphonsus, Wally walked on crutches or with the assistance of a cane. His leg bones were wrecked. He was inside a body foreign to the one he knew for all his life.

The bone grafts on his femurs left him inches shorter. Walking was tough. He winced getting out of a chair. Climbing stairs was a task filled with anguish.

“He had some miles on him from the accident,” his friend Jeff Wragg added. “It was hard for him to get around. And you could just see it in his face.”

It led him to dark addictions. Plenty of drugs. Alcohol. And more alcohol. On a drive to Arizona, Wally sat shotgun, asking Bouton to stop at every liquor store along the way. For hundreds and hundreds of miles, Wally would have Coca-Cola in one hand and a fifth of Black Velvet in the other, switching between swigs for hours.

“Towards the end,” Bouton said, “he had a death wish. He just couldn’t take the pain and the struggle.”

For so much of his final 19 years on Earth, Wally needed to escape his reality. It was skydiving that brought him peace.

Despite all the reckless and outlandish activity that Wally’s friends have a million stories to prove, he so dearly, dearly loved skydiving that he spent the majority of his life passing that love on.

Before the accident, he opened Jump West Parachute Center in Star — known to everyone as simply “The Drop Zone.” Asked how he afforded to buy it, Denton, Miller and Bouton start cackling.

“Well, he never bought it,” Denton says. “You have to understand the Drop Zone was way out in the boonies back then. There was nothing around there.”

There was something. A local man named Tom Foster and his family owned the land and operated a drag-racing strip that went out of business after Firebird Raceway opened in Eagle in the late ‘60s. So by the time Wally came around, the land was vacant, save for a bunch of Foster’s cows.

“There was a bunch of cattle rustling back in those days,” Denton says, “but as long as we were out there, there was no cattle rustling.”

So Foster allowed Wally to use the space for skydiving.

And, always on the prowl for a great business idea, Wally knew Boise State had a few extra single-level military barracks from nearby Gowen Field that were going unused. He asked if the skydiving club could have them. Wally scrounged up a few grand to move them out to Star. Fifty years later, they’re still upright at what’s now called DZONE Skydiving.

It was in its infancy when Wally crashed, which might have been a problem if the skydivers paid any rent.

Calling the Drop Zone a “business,” would be putting the word in the loosest possible term.

“Did I mention he had no money in the Drop Zone bank account,” Miller said with a laugh.

Wally started it, kept tabs on it while he was in the hospital and kept it afloat long enough to build a community.

Fifty-two years later, the video of the Bronco Stadium jump still turns Wally’s friends into statues. They stop joking, stop talking, stop moving. Time can soothe over plenty, but it rarely erases the shock of true horror.

Or the sadness of a long-lost friend.

That 1989 KTVB newscast was about Wally’s funeral and for the story, his friends gathered on the 40-yard line of Bronco Stadium. The green turf was now blue. And at the spot where Wally plummeted, where his youthful, promising life tipped on its head, his buddies remembered Wally the best way they knew how: with humor and stories.

Technically, he died of a heart attack at the age of 46. From his friends’ perspectives, he died of a hard life, finally succumbing to 20 years of waking up every day with unbearable pain masked with drugs and whiskey.

After Wally’s funeral, a wake was held at Veterans Memorial Park, where a few hundred spectators looked to the sky as Denton, Miller and four other skydivers parachuted down. Before they pulled their chute, the six men linked their arms together in a semicircle, leaving a big opening for a big personality gone too soon.

Jody Piechura doesn’t remember a ton about his Uncle Wally — he was a baby at the time of the crash — mostly the stories his mother, Wally’s sister Sandra, shared throughout the years. But the walk to his uncle’s funeral still brings back such a clear image. Piechura was in the Army then, dressed in his military uniform, which wouldn’t have been a problem if not for the trek.

“You had to walk at least a quarter mile up there,” Piechura said. “There were so many people there you could hardly get anywhere.”

Wally did not have any children. He had two siblings and very few relatives after that — so few that when asked by phone what other family members of Wally’s were still alive, Piechura couldn’t think of a single name.

And yet, Wally was so revered that parking at his funeral became harder to find than a skydiver without a Wally story.

“I was surprised people showed up. My God,” Denton said. “He did a lot of drugs, chased a lot of girls, did a lot of crap. And you would’ve thought he was an outstanding citizen.”

In some ways, Wally’s life was the antithesis of service. Aside from his time in Vietnam — serving as a forward observer in the Army, Denton thinks — where his buddies said he began skydiving, he held no distinguished job. He was not this charitable saint or some warm-hearted, loving soul. But, man, was he memorable.

He was outgoing, loud, armed with “a voice that would be prominent in a room full of voices,” said Wragg. He rented a house, at 2812 Montevista Drive in east Boise, that basically operated as a free hostel for skydivers. And, let’s just say it wasn’t uncommon for people to parachute into the Montevista house cul-de-sac, or miss and end up in someone’s backyard before heading into Wally’s place.

Wally had goals, ambitions, ideas and the confidence to verbalize those things. To actually ask for those things. So much regret often stems from not doing something, not asking for something, not taking advantage of a moment. Wally never had that problem. It’s how he started up the skydiving club. He simply asked Bill Jones if he could form it. It’s how he skydived into the first game at Bronco Stadium. He had an idea and asked.

Not all were smart or successful. He had one especially idiotic plan to start a commune at his grandparents’ farm in Montana, built on the idea he could raise goats, feed the goats to catfish and sell the catfish to Native Americans. It never materialized.

Wally almost arranged for 10 of his skydivers to do a demo jump ahead of Evel Knievel’s very famous and very unsuccessful leap over Snake River Canyon in Twin Falls. But he held out for more money that never came.

Years later, as his mobility diminished and his alcohol intake peaked, Wally and Bouton were taking that aforementioned trip to Arizona. Wally made them pull over in the small town of Lund, Nevada, because he saw farms littered with metal windmills and thought he had stumbled upon a gold mine.

He stopped at a local ranch and began talking to a family about maybe purchasing one, which didn’t happen. But the family’s young son saw the skin grafts along Wally’s wrecked legs and asked him what the heck happened.

“I fell on a landmine in Vietnam,” Wally told the kid.

That was Wally Benton, the guy who felt the need to exaggerate a 100-foot skydiving crash into a football stadium.

“Everything had to be more grandiose than it actually was,” Bouton said.

Miller was a young Boise State student the first time he skydived at the Drop Zone in 1972. Now, 3,000 jumps later, he sits on a couch, his hair much lighter and thinner with his heart full because Wally wouldn’t let him quit.

Miller was the opposite of a natural, a “swimmer” in the sky with little confidence and little control. Tom Sullivan, a former member of the skydiving club, was Miller’s instructor. He was not impressed, telling the college kid, “You know, not everyone who comes out here to make a jump is cut out to be a skydiver.”

Wally must’ve overheard the conversation. Later that day, he cornered Miller.

“Hey, let me tell you something,” Wally said, “You can do it. I know you haven’t had the best start. But if you just stick with it, that fear thing will go away.”

The man who no longer jumped from airplanes spent the back half of his life helping others experience the thrill he could not.

The Drop Zone is where Denton and Miller and Bouton and all those people from the funeral met each other. Where they developed relationships and forged their own passion for a sport built on adrenaline. Wally’s legacy is alive in stories told every day in the Treasure Valley — the ones about skydiving competitions, parachute evolutions and flybys and a million rough nights at the bar.

“You have to know something,” Denton said. “All of our crazy stories usually happened because of one guy. And there’s like 20 people who can say that about Wally.”

And just as he preached to Miller and so many other amateur skydivers, Wally didn’t succumb to the fear. He didn’t quit.

There was never another jump to dedicate the stadium. But Wally made one last jump in his life.

In June 1976, Wally walked over to his Cessna, chucked his crutches and readied to skydive for the first time in six years. There was nothing special about the day.

Perhaps he just got fed up sitting on the sidelines. Perhaps his sanity needed another jump, to put the Bronco Stadium crash behind him. Perhaps he wanted to show all his friends that the injury hadn’t broken him, that he was still the same determined Wally.

He jumped, this time with a round canopy. But because Wally’s legs were too brittle for a hard impact, a few friends stood on the ground holding a sleeping bag to try and catch him in. Problem was, it was a windy day in Star. They chased Wally as he floated to the ground, grazing him with the sleeping bag but not securing him.

He suffered a broken leg and, just like his previous jump, ended up at the hospital.

This time, though, he didn’t have to stay the night. Progress.

This article originally appeared in the Idaho Press, read more on IdahoPress.com.

See the latest news from around the Treasure Valley and the Gem State in our YouTube playlist: