'You die a 1000 times on death row before they pull the switch': Life after being wrongfully convicted

There are approximately 2 million people incarcerated in the U.S., and experts, statistics say at least 4% of them are innocent.

A person spending years, decades or life in prison for a crime they did not commit may seem unimaginable, however, for many it is a reality. Jamie Ellsworth, a lawyer with The Idaho Innocence Project said research shows up to 4% of inmates are actually innocent. If two million people are currently incarcerated in the United States, it follows that thousands of innocent people are serving time for the crime of doing nothing wrong.

"In the state of Idaho, we have more than 8000 inmates," Ellsworth said. "That means there's hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of innocent people that are in jail right now for crime they didn't do. That also means there's hundreds and hundreds of perpetrators out there who have not been caught yet. So, I think it's important to know that it's, unfortunately, more common than most people would like to believe. And given an imperfect storm, anyone could be wrongfully convicted."

That is exactly what happened to Glynn Ray Simmons.

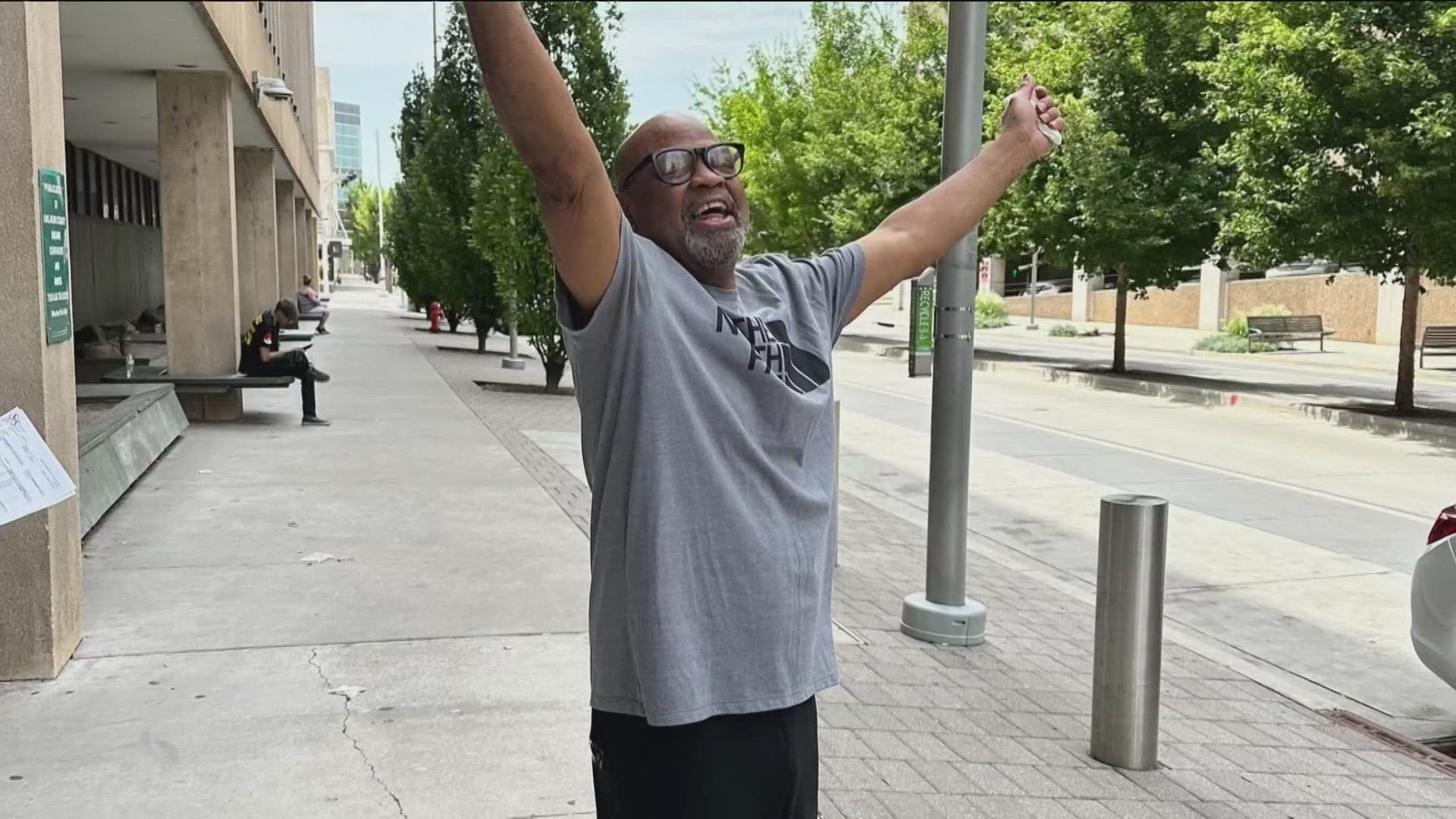

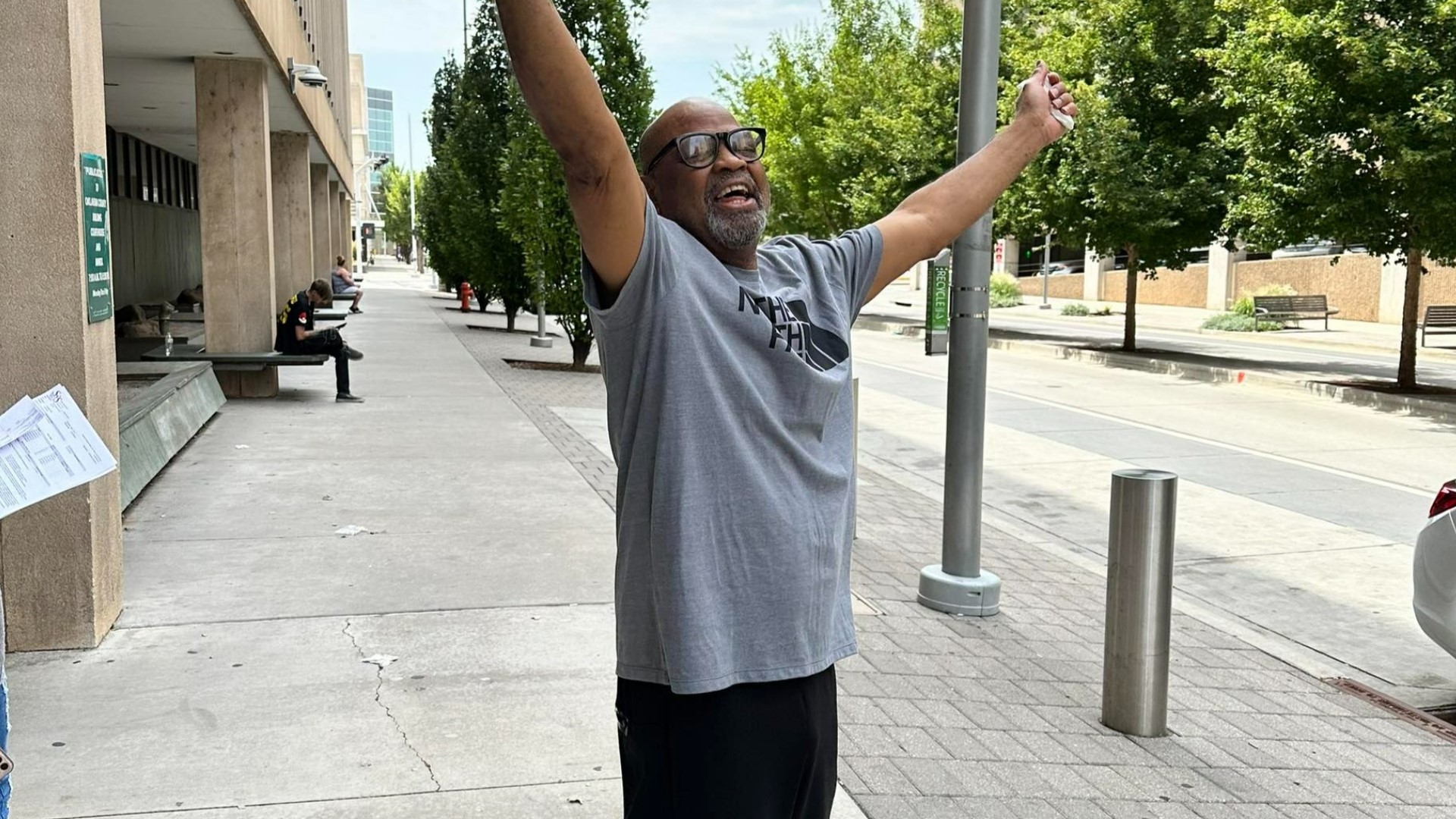

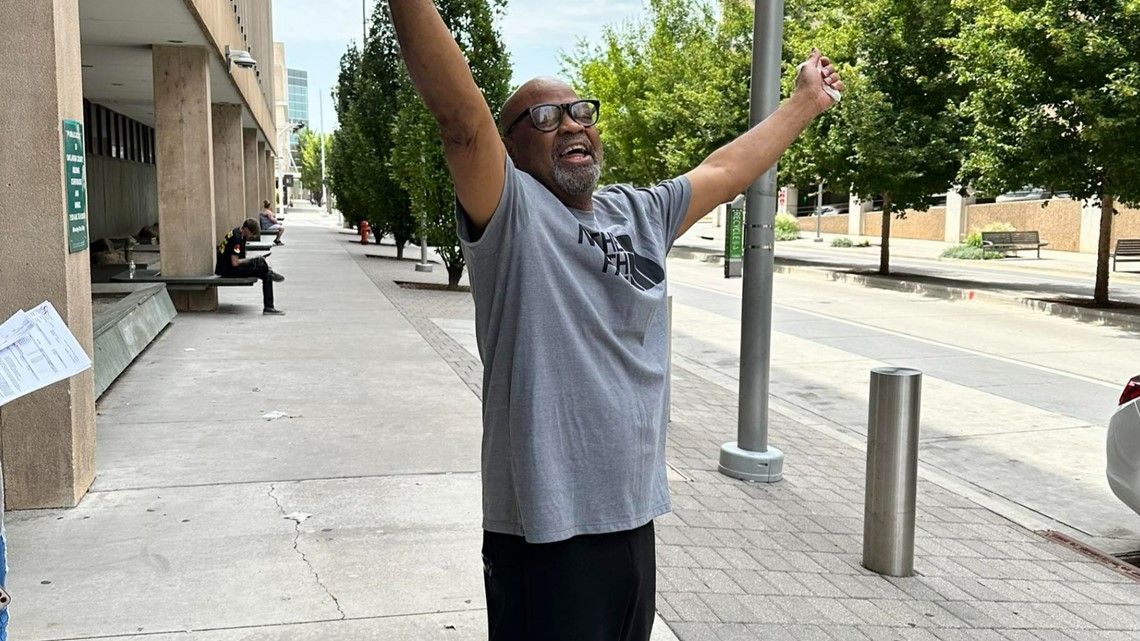

Wrongfully convicted in Oklahoma 48 years, 5 months and 13 days.

Simmons was 21 years old when he was wrongfully convicted in Oklahoma. He spent forty-eight years, five months and thirteen days in prison for a crime he did not commit; Most of his life.

"It was hell. Absolutely. It was hell," Simmons said. "I was released July 27. My case, the conviction, was vacated due to a lack of evidence, suppression of evidence and everything. But I got locked up in 1975 on a murder, a murder case that I didn't commit. And [in a] town that I had never been to."

He was put on death row and lived everyday in a cell, waiting to be put to death for a crime he had no part in.

"You couldn't imagine I couldn't even describe -- even describe it," Simmons said. "You die a thousand times on death row before they pull the switch. every day. So, you know, it was a lot of trauma and stuff."

What he experienced is something that may be hard to imagine, yet, it is happening all over the nation. Living on death row, caught in a system that caught and punished the wrong person.

In July of 2023, Simmons was released from prison after a judge vacated his sentence. A new trial was never opened, the judge said evidence was withheld at the original trial. His attorney said Simmons was the longest-serving wrongfully convicted man in the nation's history.

The Idaho Innocence Project Uncovering truth through science.

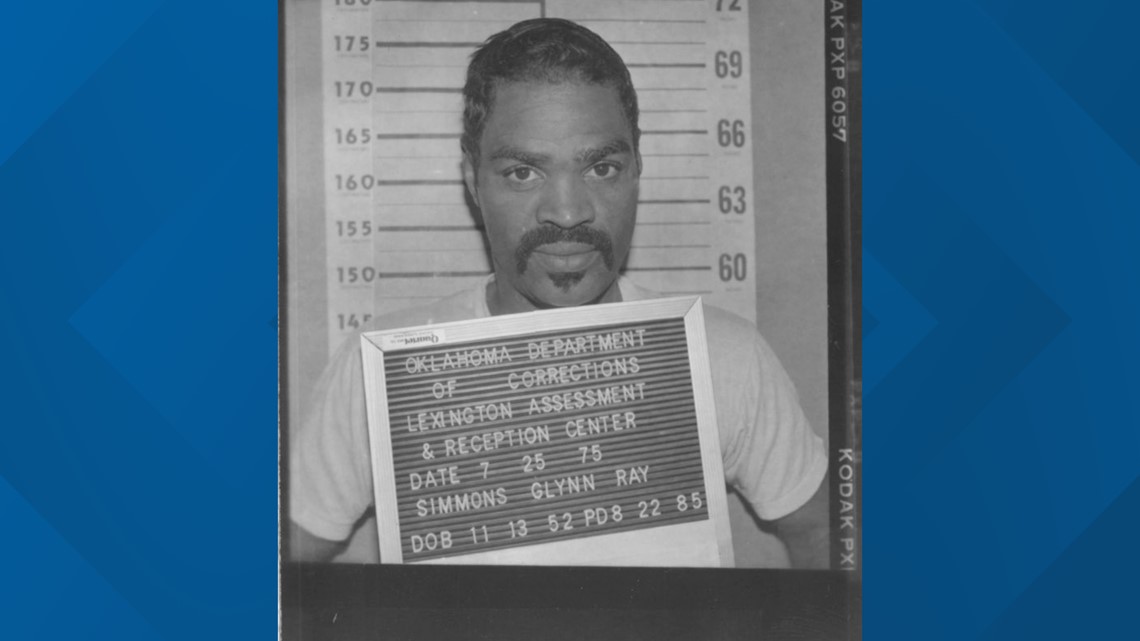

Dr. Greg Hampikian, the Co-Director of The Idaho Innocence Project and professor of biology at Boise State University has spent decades getting innocent people out of prison with DNA exoneration.

"We see a lot of tragedy. When people get out, we see a lot of success," he said. "The easy part is the DNA. The very difficult part is getting the calls from people while they're in prison. And then dealing with the family sometimes who, you know, we come to love and know. And sometimes they pass on, while their loved one is in prison even, when we get someone out."

Hampikian said at The Idaho Innocence Project the process of helping people who have been wrongfully convicted begins with stacks of letters sent by prisoners. Legal advisors and volunteers then sort through them, trying to find cases where they can be of help.

"I oversee it from the moment we receive a letter up until we go to litigation to try and get a court to try and overturn a verdict and release an inmate," said Ellsworth.

Ellsworth said there are certain criteria they look for in the initial letters. Things like did the crime happen in Idaho, is the person claiming innocence and the length of the prison sentence. After that, the prisoner is sent a questionnaire.

"This is really just to get a lot more information about their trial, where they think things went wrong, what they see as a basis for their innocence," Ellsworth said.

Following the questionnaire, the team rounds up trial documents and investigators begin to comb through the old cases looking for something new or something that was skipped over.

"Then we will either reject or accept somebody," Ellsworth said. "Once we accept them, then we formally start looking for any avenues to get them out of prison."

Finding DNA and using scientific methods has helped the Idaho Innocence Project free many people from prison who should have never been there in the first place.

Ellsworth said in most wrongful conviction cases, the biggest factor is often misidentification.

How wrongful convictions can happen False confessions and pseudoscience

A person may be wrongfully convicted for two reasons, either because the person convicted was factually innocent or there was some kind of error, usually procedurally, that happened during the arrest or trial. In any case, it boils down to human error.

"A lot of people think our brains work like cameras like the camera that records and we can just hit pause and rewind and replay our memory," Ellsworth said. "But science has routinely shown that our brain doesn't work like that, it's really much more like a collage. And we pieced together a little bits and pieces of information. But we have a lot of blank spaces."

False memory can be a factor, so can false or coerced confessions and even pseudoscience.

"Or junk science," Ellsworth said. "20 years ago, the field of science looks a lot different than it does now. So, the arts and science that existed 20 years ago has shown to be fundamentally flawed, and not really based in science. At the end of the day, you mostly have to show that the jury would have had a reasonable doubt in their mind, or the outcome would have been different."

Christopher Tapp Local man wrongfully convicted, exonerated by the Idaho Innocence Project

Christopher Tapp was one of the people helped by Hampikian and The Idaho Innocence Project. The Idaho Falls man was wrongfully convicted in 1997 for the rape and murder of then-18-year-old Angie Dodge.

Tapp spent 20 years in prison until his innocence was proven in 2017.

"That was one of the most satisfying days of my life," Hampikian said. "I think it's over, you know, there's nothing else I can do. What all the exonerees want, is just finished the story. Like just finish it, you know, you can't give me my life back. But find out what happened."

Hampikian said they worked on the case for ten years before Tapp was released from prison. It was another five years before they finished the case and found the perpetrator.

"You're working on these cases for years, how do you, keep that hope?" Hampikian said. "I remember the successes. And, I don't remember them as Oh, boy, that was great. Everybody's happy. I remember it as people in my organization told me we'd never finished this case, or this person was guilty. Or, you know, why are we wasting our time on this, and, and then they get freed because of diligence, because of persistence."

Following his release, Tapp joined The Idaho Innocence Project as a policy advisor

After a mere six years of freedom, Tapp died following an accident in Las Vegas at the age of 47, he had spent almost half his life in prison for a crime he did not commit. DNA evidence helped exonerate him.

The price of wrongful conviction Can injustice be overturned with monetary compensation?

If there has been gross negligence, or other factors that have contributed to a wrongful conviction, there is a possibility the person can recover additional damages in the form of monetary compensation. Money does not buy back time but it can help the person regain footing in society.

In Tapp's case, he received a settlement of $11.7 million from the city of Idaho Falls.

Ellsworth said Tapp actually helped pass legislation to help wrongfully convicted people get compensation, "previously convicted inmates who were wrongly convicted can receive a certain amount for every year they were wrongfully convicted."

The amount is $62,000 per year.

"We're very happy with that number. A lot of people ask, Would you be willing to go to prison for 62,000 a year, but it's better than nothing," Ellsworth said.

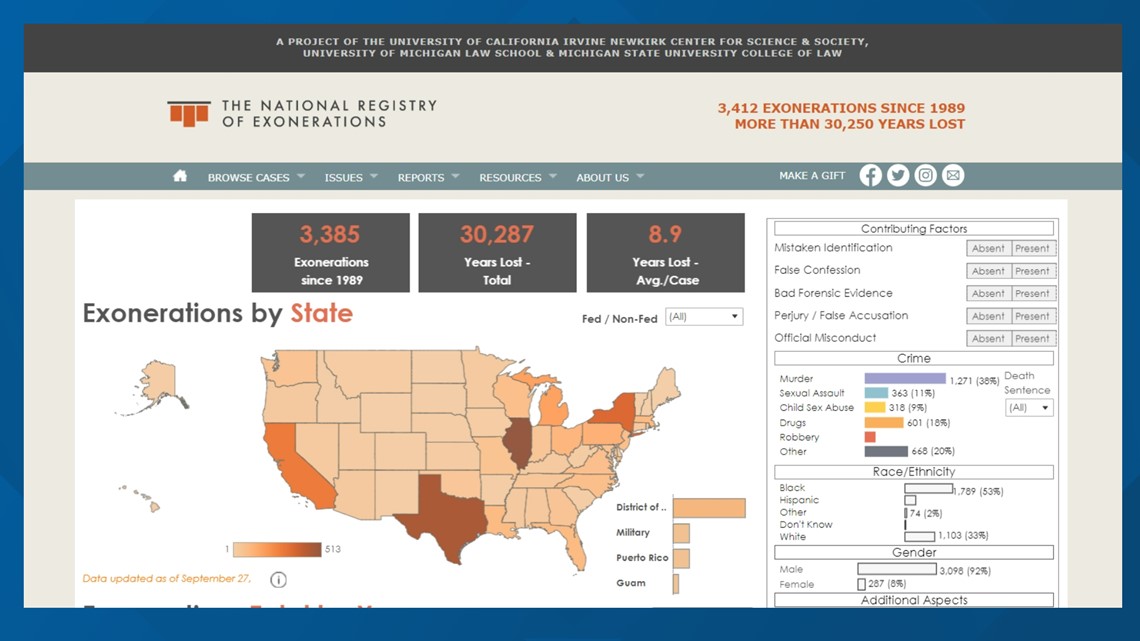

Tapps' case is also documented with the University of Michigan's National Registry of Exonerations

The registry found more than 3,300 wrongfully convicted people have been exonerated in the U.S. since 1989. Further, although minorities like Black and Latino people have smaller populations in the country overall, they are up to 7% more likely to be wrongfully convicted.

Ken Otterbourg is a researcher with the registry. He said the purpose of it is to bear witness to these wrongful convictions.

"We like to say we are a living archive of injustice," Otterbourg said. "So, over time, what we've been able to do is show that what people think are anecdotal problems that lead to convictions ... there's patterns that [are] evolved that you can show."

He added that people who have been wrongfully convicted also use the site as a resource.

"There was a person who was having trouble getting like a driver's license, or some sort of state ID, and they pulled up their page to show the clerk who they were.," Otterbourg said. "So, you know, it's something they can show their friends and their family. And it's a validation of what they went through."

Life after a wrongful conviction Rejoining society

Hampikian said the people who get exonerated are absolutely traumatized by their experience.

"It ain't like the movies," he said. "The movies have music. We don't have music in lab. You know, they don't have music when they're alone at night. And every single one of the people that I've worked with who get out have horrible nightmares."

As for Simmons, he is now trying to rebuild his life. He said it has been a struggle and he thinks the adjustment will take time.

"Every day is gets better and better for me. I guess because I come from such a dark place that you know, you know, everything was good is better and I'm sure I'm truly appreciate it," he said. "It's been good, it's hard. I mean, I don't make it like it's a fairytale. It's hard you know, but I adjusted [to] some real hard stuff over the years so this is not you know, the worst of all possible worlds, this the best to me."

He is rediscovering the world. Trying to make up for lost time and learning about what he has missed.

"They just came out with microwaves, it's a whole new thing there wasn't no cell phones and all of that," he said, "everything, your car talking to you, all this stuff is new to me but I'm excited."

48 years of lost time.

"I want to be known for more than the guy who done 48 years and was released," Simmons said. "That's not all of me. That's what happened to me. But that's not who I am."

Simmons added that he was grateful for those who supported him and he wants to dedicate his life to prison reform after he gets re-established, he has a GoFundMe to help with that. He hopes to start a reintegration program to help others in his situation.

For people who'd like to get involved with exoneration, The Idaho Innocence Project is always looking for volunteers.

KTVB digital producer/journalist Tracy Bringhurst contributed to this story.

Watch more Local News:

See the latest news from around the Treasure Valley and the Gem State in our YouTube playlist:

HERE ARE MORE WAYS TO GET NEWS FROM KTVB:

Download the KTVB News Mobile App

Apple iOS: Click here to download

Google Play: Click here to download

Watch news reports for FREE on YouTube: KTVB YouTube channel

Stream Live for FREE on ROKU: Add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching 'KTVB'.

Stream Live for FREE on FIRE TV: Search ‘KTVB’ and click ‘Get’ to download.