CALDWELL, Idaho — Georgia Carrera wanted out of the minivan, but police cars were already in pursuit, and Joe Nevarez wasn't inclined to pull over.

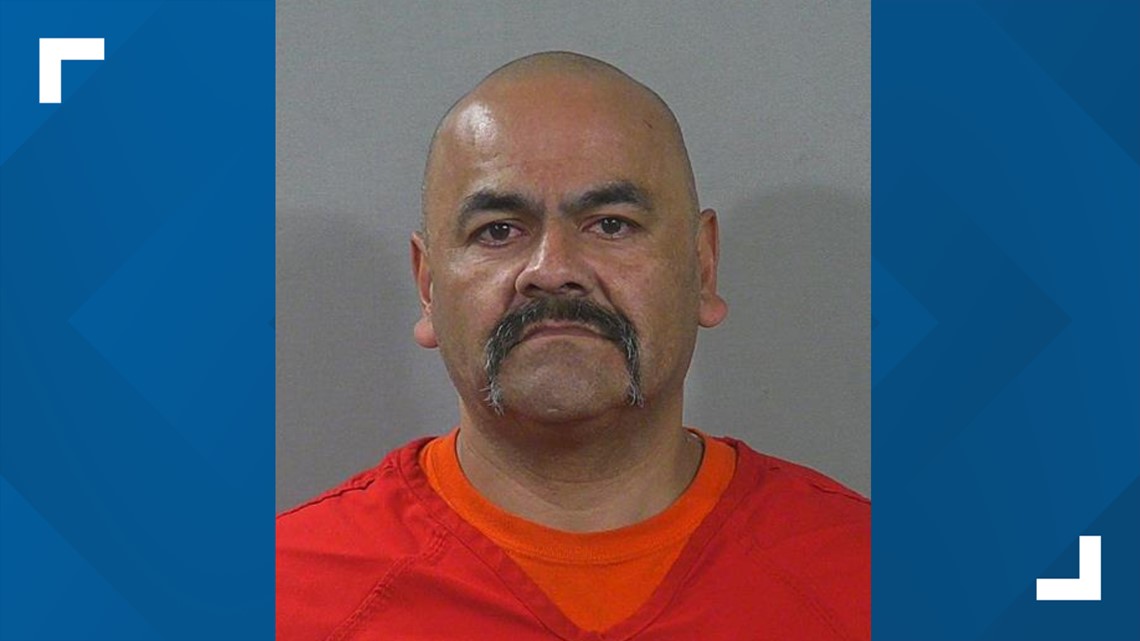

The situation had started shortly after midnight on Feb. 13, 2018, when 46-year-old Nevarez had peeled away from a traffic stop, knocking a police officer to the ground. Officers said later he was driving double the 35 mph limit, running red lights and hitting street drainages hard enough to throw up sparks.

Carrera, Nevarez' friend and passenger in the van, had not signed up for a high-speed chase. She asked him to stop so she could get out.

Nevarez didn't.

As he rounded the corner onto 2nd Street and 18th Avenue - 0.4 miles and less than a minute from the spot the pursuit had begun - Carrera fell or jumped from the speeding vehicle.

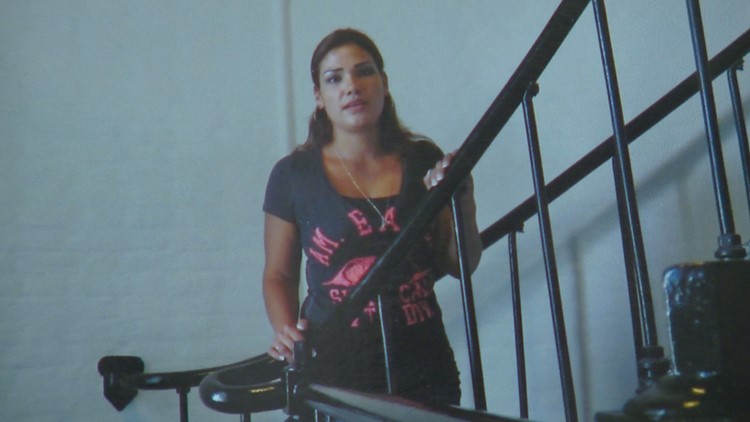

The closest police officer behind Nevarez did not see her lying in the intersection. His patrol car struck the 36-year-old mother of three, then rolled over her.

'WE NEED HER EVERY DAY'

Nevarez was sentenced Monday to spend at least two years in prison, with the possibility of remaining behind bars for eight-and-a-half years.

The sentence came as part of a plea deal that saw Nevarez admit to felony charges of meth possession and eluding, but only a misdemeanor charge of vehicular manslaughter in Carrera's death.

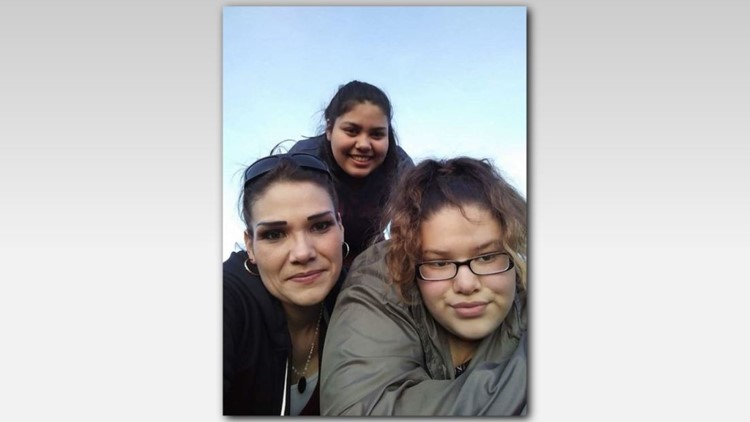

At the sentencing hearing, Carerra's second daughter told Nevarez that she has not been able to bring herself to forgive him, and reminded him of a promise he had made her when they first met.

"You told me, 'don't worry, I'll take care of your mama for you,'" the 16-year-old said. "I trusted you. You knew she had kids. She had a family to come home to."

Carerra died just 26 days before the girl's quinceanera.

Nampa woman run over by police leaves behind two daughters and a son

Her older daughter, Jessica Sierra, turned 18 without her mother around to celebrate with her. Carrera will not be in the crowd at her graduation next year either, Sierra told Nevarez. She will miss her children's someday weddings, and the births of their own children.

"She was always there, no matter what. My mother had her struggles, but we loved her all the same," Sierra said. "We have no way to contact her when we need her, and we need her every day."

The victim's third child, an 11-year-old boy, did not attend at the sentencing: He was too young, prosecutors said, to grasp what was going on.

THE CHASE

Nampa Police Officer Mason Foster was on a nightshift patrol when spotted Nevarez' dark-colored minivan make a turn from 2nd Street to 16th Avenue without using a turn signal early Feb. 13, 2018.

Foster flipped on his lights, and the driver pulled over into the parking lot of the Gem Stop, the officer testified at an earlier preliminary hearing in the case.

By the time he got up to the driver's window, he said, Nevarez was already "very agitated."

"He started to cuss at me, and he said that I was harassing him," Foster testified.

The officer ran both Nevarez and Carrera - who had given a relative's name as her own - for warrants, and called in a drug dog to sniff around the minivan. When the dog alerted on the vehicle, Foster said, he asked Nevarez to step out.

"At that point, he said 'oh f--- no,' and he drove off," the officer testified. "I could hear the tires squealing and I heard burnt rubber as he drove away."

The minivan clipped Foster's knee as Nevarez accelerated, knocking him down.

Another officer who had joined the traffic stop, Nampa Police Cpl. Bryce Martin, immediately gave chase. Foster jumped back in his own car and followed.

Neither Martin nor Foster saw Carrera leave the van, and Nevarez said he only later realized she had jumped or fallen out. Martin testified at the same preliminary hearing that he ran over something at 2nd Street and 18th, but did not know he had hit a woman.

"I had no idea what it was," he testified.

It was a third officer, K-9 handler Brad Boster, who realized that someone was hurt.

"As I traveled or approached 18th Avenue South on 2nd Street South I observed a bag and a sweatshirt in the road," he testified at the preliminary hearing. "I drove wide around the corner to avoid those and found a body laying in the road."

Carrera had suffered massive head trauma, and died at the scene. A coroner later determined that she was killed by Martin's patrol vehicle, and that there was methamphetamine and amphetamines in her system when she died.

Nevarez, who also admitted to using meth before the pursuit, kept driving, hitting 90 mph before a wheel flew off his minivan and hit Foster's car. Martin then rammed the vehicle, bringing it to a stop.

Nevarez jumped out of the van and fought with the two officers before being taken into custody.

HEADED TO PRISON

Prosecutor Chris Berglund told the judge that Carrera's death had deeply affected Martin as well as the victim's family.

A Critical Incident Task Force investigation cleared the officer of any wrongdoing, but he was left "traumatized," she said.

"He is devastated, and I want the family to know, Georgia Carrera's life mattered to him as well," she said. "He will never, ever get over taking an innocent life."

Even if Nevarez did not intend for his friend to lose her life, Berglund argued, he was ultimately the one responsible what happened: He had chosen to flee the traffic stop at high speeds, and had admitted that he did not pull over when Carrera said she wanted out.

The prosecutor also noted that Nevarez had run from police before, and that he had previously failed to comply with his probation. Berglund urged the judge to stick to the terms of the plea deal, and sentence the defendant to a prison term.

"He does not seem to be of a mind to comply with authority, and this time it cost someone their life," she said.

In a brief statement before the sentence was handed down, Nevarez told Carrera's family that he was "deeply sorry" for what had happened. The victim's mother and her children all asked for - and were granted - a no-contact order that prohibits Nevarez from reaching out to them from prison or coming around after he is released.

Judge Thomas Whitney pronounced a fixed sentence of three-and-a-half years, with two indeterminate terms of a year-a-half, and five years to run consecutively, as well as a year in jail, which runs concurrently with the prison sentences. Because Nevarez has been held in jail since his arrest, with credit for time served, that works out to about two years before he can become eligible for parole.

Whitney told the defendant that he hopes he can make the most of prison programs while he is serving his sentence, and someday function in society once he is released.

Carrera's 16-year-old was thinking of someday too. In the future, when she is older, she said, she might come to the point where she could forgive Nevarez for what happened that night in Nampa.

But not yet.

"I'm still a girl who has to live a life without a mother," she said.