BOISE -- Predicting an earthquake is impossible. But imagine if you could be warned when one is heading your way?

An earthquake early warning network is being used in Japan and has been in Mexico for the past 20 years.

However, in the United States, we are just in the early stages of installing a similar system across the West Coast. The software would be able to give a moment's notice to those that may be in danger.

But would that program be feasible in Idaho?

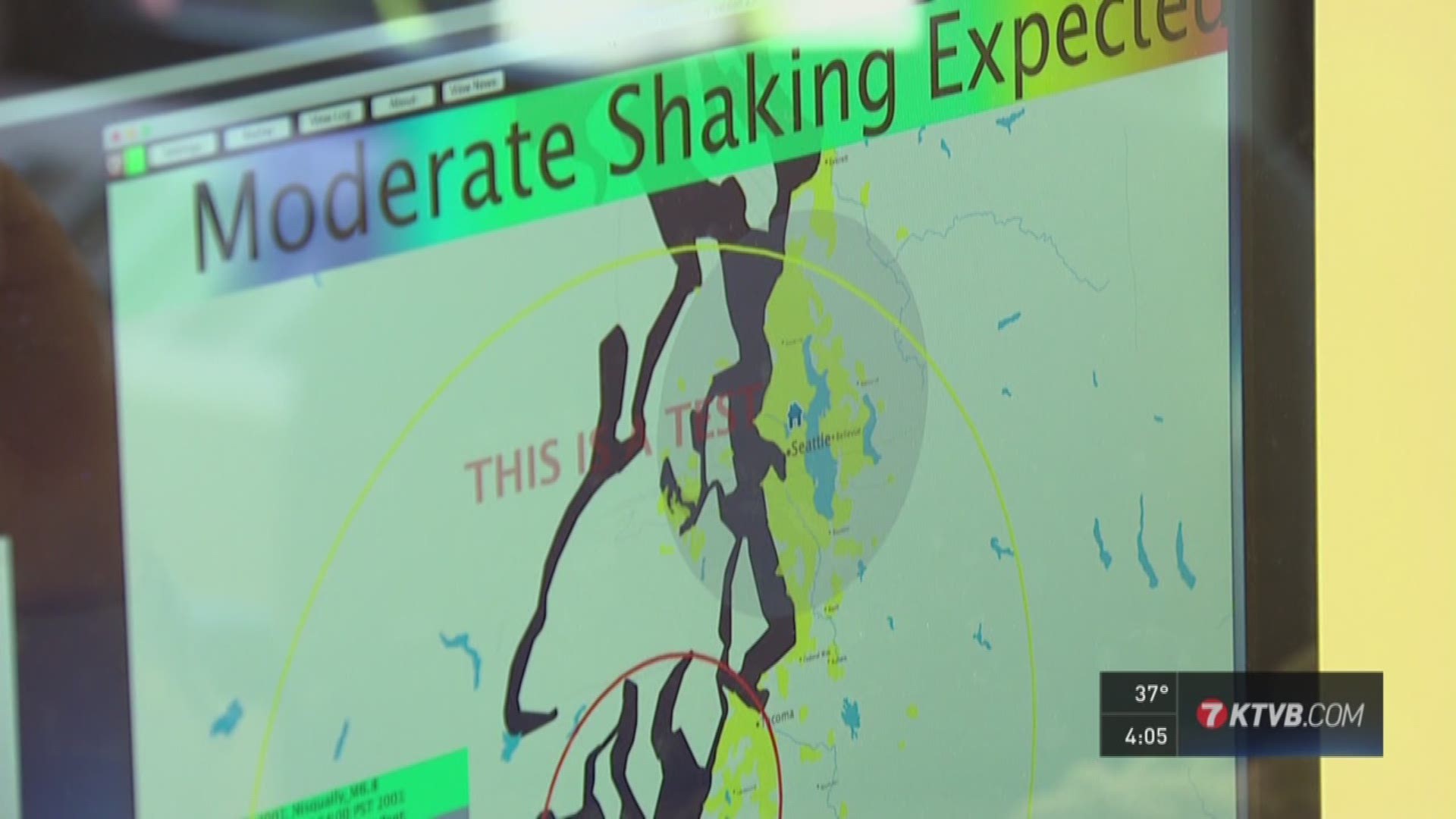

It's called ShakeAlert, an Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) system being put in place by the U.S. Geological Survey. The goal is to give a notice of seconds, and maybe minutes, to cities within the range of the tremor.

Fire station doors would open automatically, transportation could be stalled, and people could seek cover.

A pilot program is expected this summer, with a smartphone app shortly behind that.

The infrastructure of monitors is already in California and in many locations across Oregon and Washington. But not in Idaho.

"This map shows the earthquakes that have happened in the last 24 hours," said Lee Liberty, a professor of geophysics at Boise State University for more than 20 years, is showing the seismic instruments in the Environmental Research building.

He knows about the early warning network that has become a priority across the West.

"We're able to say, 'Oh, we just felt a P-Wave, expect that surface wave to come,'" said Liberty.

He said seismic sensors would pick up what is called a P-Wave, a fast moving compression wave that spreads from an earthquake epicenter.

"They arrive seconds or minutes before the large ground shaking," said Liberty. "What we call ground roll or surface waves."

It is a system that would take about $40 million to put in and another $16 million to maintain each year. Money is just one reason ShakeAlert is unlikely in the Gem State any time soon.

Liberty said just putting one monitor in the ground could cost $10,000. Of course, increasing the number would increase the accuracy.

"In California it's tens of miles from monitor to monitor. In the Pacific Northwest, it's even worse than that. In Idaho it's hundreds of miles between sensors," said Liberty.

The other reason is the state's lack of seismic activity. Despite being in the top 10 of most active states, the last big quake in Idaho was a 6.9 magnitude near Mount Borah in 1983.

So that's why the focus remains on the West Coast.

"I see the higher priorities are the Cascadia fault, which is Oregon and Washington, and California. Those are by far the highest hazard in the lower 48," said Liberty.

Two children in Challis were killed walking to school in that 1983 earthquake. But how about populating monitors in more populated areas like the Treasure Valley?

Liberty says there are faults in the valley but over the last hundreds of years there has not been any motion in them. That's not to say it won't happen. Liberty likens earthquakes to winning the lottery -- there's always a chance but not a guarantee.