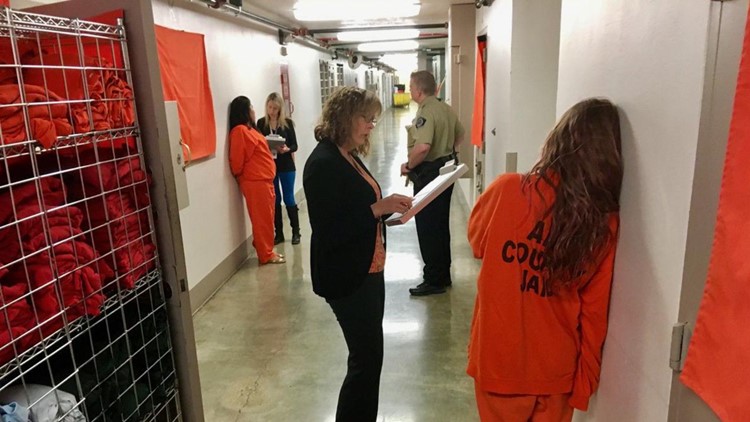

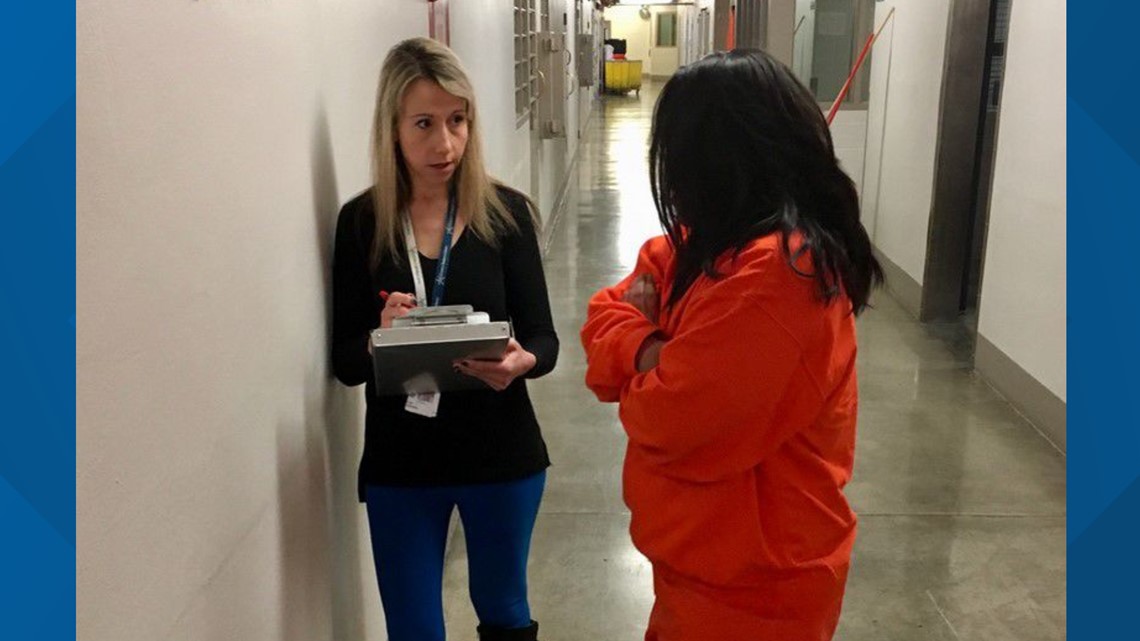

BOISE, Idaho — As close to an arrest as possible — and usually within 24 hours — someone from the Ada County Sheriff’s Office Pretrial Services Unit will meet with most people booked into the county’s jail.

Their job is to interview the person about their circumstances and evaluate them with an eight-question survey using what's called the Idaho Pretrial Risk Assessment Instrument or IPRAI, according to a report in the Idaho Press. The goal of meeting with a person and using the tool is to find out how likely the person is to show up to court or commit a new crime if released. Judges then are able to use that information when deciding whether to set bond for a person ahead of future court dates.

In Ada County, judges and sheriff's office employees have been using the IPRAI officially since February and began using a revised version on Nov. 1.

But it’s not a new technique. The IPRAI is based on a model used in Virginia. Canyon County also uses Virginia's model, with one slight change pertaining to how the tool deals with information about a person's failure to appear in court, according to Joe Decker, spokesman for the county. The county has done so since 2009, Decker said. Other states use similar tools.

But the use of such methods has raised concern among some advocacy groups and politicians — including in Idaho — that the tool paints minorities as more likely to commit crime or miss court if released, and thus make them less likely to receive affordable bail.

However, Ada County Pretrial Services Unit Manager Katie Martin believes the IPRAI actually evens the field rather than skewing it.

“A lot of bail decisions are focused around money,” she said. “And that’s not how it should be.”

PRETRIAL SERVICES UNIT

Nine people work in the Pretrial Services Unit, Martin said. About half manage the cases of those released from jail ahead of their court dates. The other half interview inmates using the IPRAI survey six days a week. The survey and interview process can take from 15 to 20 minutes or up to a few hours, Martin said.

Since February, the unit has conducted about 5,700 such assessments, according to the Ada County Sheriff’s Office. Of those, the office says, 91% did not commit new crimes after their release from jail.

It’s paramount those reports are accurate, timely and complete, said Martin, adding that a report is considered unusable if it does not include an interview with the defendant.

Questions on the survey — such as those asking if a person is currently being supervised by law enforcement or if they’ve failed to appear in court two or more times — are worth a set amount of points. Surveyors combine those points for a number between zero and 14. Based on the score, the defendant is placed into one of six categories estimating their risks of committing another crime and not appearing in court.

In addition to the eight questions used to calculate a person's risk score, surveyors ask additional questions, such as if a person has a high school diploma or a GED, or a valid driver's license.

An IPRAI report is given to a judge before a hearing at which a judge sets bond. Typically, that happens within 24 hours of a person's arrest. Prosecutors and defense attorneys regularly cite an IPRAI score when arguing for or against a defendant’s release. Judges reference those scores when deciding how to set bail in a given case.

“The tool is really there … as an additional piece of information so (judges) can make a better-informed decision,” Martin said.

The IPRAI report is meant as supplemental information, said 4th District Administrative Judge Melissa Moody. Judges aren't bound to make decisions based purely on the score alone. Judges don’t lose any autonomy — they simply gain more information because of the IPRAI.

“The judge has all of the discretion the judge has always had,” Moody said.

CONCERNS

There is a national debate among academics, advocates, politicians and those working in the criminal justice system about whether risk-assessment tools make the justice system more or less fair.

In July, for instance, 27 researchers from some of the country’s top universities — including Harvard and Princeton universities and the Massachusetts Institution of Technology — signed an “open statement of concern” regarding the use of risk-assessment tools.

“To generate predictions, risk assessments rely on deeply flawed data, such as historical records of arrests, charges, convictions, and sentences,” they wrote in the statement. “This data is neither a reliable nor a neutral measure of underlying criminal activity. Decades of research have shown that, for the same conduct, African-American and Latinx people are more likely to be arrested, prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to harsher punishments than their white counterparts.”

Latinx, pronounced Latin-X, is a recently adopted gender-neutral term used to describe people of Latin American descent.

The ink had barely dried on that statement when two professors from Duke University and a North Carolina State University professor penned a response, in which they wrote that the tools might not need to be thrown away immediately.

“Uncertainty is wide when predicting crime over short time intervals, but smaller when predicting over larger intervals,” they wrote. “The latter risks are directly related to the former, allowing tools to more confidently assess which individuals are higher risk than others.”

In Idaho, Rep. Greg Chaney, R-Caldwell, was concerned about the possibility that generations of bias in the criminal justice system had been woven into the IPRAI. Even if the tool doesn’t directly make a reference to race, he said, it’s possible the tool asks certain questions that “build a socioeconomic profile” that is simply rehashing the problems of bias already present.

He said he believes 33 of Idaho's 44 counties use some sort of pretrial release tool, and said when he looked for more information about the topic, there was little available.

"It was kind of a county-by-county decision on what to use," he said.

To quell those misgivings, in February, he introduced a bill in the Idaho House that would have banned the use of such tools unless counties could "affirmatively demonstrate" the methods were not biased against protected classes of people. The bill also made it illegal for governments to withhold from the public the methodology the tools use. In other states, he said, governments have claimed that information is a trade secret and thus not subject to a public records request.

The bill garnered support across the aisle: Sen. Cherie Buckner-Webb, D-Boise, cosponsored it.

It also earned the backing of the ACLU of Idaho. Kathy Griesmyer, the organization's policy director, testified in favor of the bill to the House Judiciary, Rules and Administration Committee.

"Troublingly, pretrial assessment tools … cannot avoid racial bias," she testified in February. "The predictions of (the tools) reflect well-documented and unwarranted disparities in all stages of the criminal justice system—including the fact that Black men are more than six times as likely and Latino men nearly three times as likely to be incarcerated as white men, and that white men are far more likely to be released pretrial."

On Thursday, Griesmyer said she didn't expect the bill to be as controversial as it was. She said she thought people saw the bill as an attack on the IPRAI, which is Ada County's specific tool.

"This wasn't meant to be an attack on a particular county," she said.

She pointed out the ACLU of Idaho had taken issue with the use of algorithms to make government decisions before. In 2012, the organization sued the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare after that department's algorithm led to cuts to Medicaid benefits for some developmentally disabled people.

She, like Chaney, was concerned the algorithms in pretrial risk-assessment tools would simply reflect current biases in the criminal justice process.

"I think in Idaho people think we're a predominantly white state with a predominantly white prison population, when, in fact, we over-incarcerate people of color," Griesmyer said.

She referenced a 2014 report from the Sentencing Project, which showed Idaho had the fifth-highest black incarceration rate per 100,000 in the country. The same study also found Idaho had the third-highest Latinx incarceration rate in 2014.

In the end, lawmakers cut the language banning bias from the bill. The second part of the bill did pass, though, which means any entity using a pretrial risk assessment tool in Idaho are barred from claiming the methodology the tools employ are exempt from public inspection. Idaho is the first state in the country to pass a transparency law aimed specifically at the methodology behind pretrial risk-assessment tools, according to the Electronic Privacy Information Center.

JUDGES' DISCRETION

Chaney introduced the bill because he was worried judges would simply take a person’s IPRAI score at face value and make a decision about pretrial release based on that alone.

“One of the things I was very concerned about was perhaps the judiciary would become overly reliant on just the number that got spat out,” Chaney said.

His experiences with the tools are anecdotal, he said. He knew of two Ada County cases in which judges declined to set higher bail due, at least in part, to a person's IPRAI score and that troubled him. One case involved a man accused of attacking a Boise police officer with a pair of scissors. Another involved someone who had about six prior failures to appear in court.

"The anecdotal evidence I've heard, though, is very concerning, that (the IPRAI) is being overly relied on," he said.

If that were happening, Moody said, she would be concerned, too. She doesn’t believe that’s happening in Idaho’s 4th Judicial District.

“If (judges) just look at a number and say, ‘Well, that’s what I’m going to do,’ that would be very concerning to me,” she said.

Judges have retained all their discretion — they’re just receiving additional information, she said. Even before the IPRAI went into use in Ada County, state law required judges to consider 10 factors when setting bail, as outlined in Idaho’s Criminal Rules, she said.

Plus, the Ada County Sheriff's Office Pretrial Services Unit has also always been working to identify which people would be suitable for pretrial release, Orr said in an email to the Idaho Press.

"The pretrial unit now has more tools, information, and employees assigned to it than ever before," he wrote.

While Moody said she couldn’t speak for any other states or jurisdictions, she also said she felt judges in the 4th Judicial District are not relying on the IPRAI without exercising their discretion. She said defense attorneys are also present at every hearing in Ada County in which bond is discussed. That’s not the case in other parts of the country or even some other parts of Idaho.

“As far as the judges are concerned, they have all of the discretion they had previously,” Moody said.

CHANGES

Already, the Pretrial Services Unit is using a different version of the IPRAI than what they started with in February.

"The revised assessment has shown to be a better predictor of an individual’s risk to commit new crimes or fail to appear at court hearings than the former assessment," Martin wrote in an email to the Idaho Press. "Many jurisdictions who are using Virginia’s model like us are using the revised version."

For example, one of the questions included on the survey in the initial model, Martin said, inquired whether the interviewee had a job. Previous versions of the tool had asked about a person's employment in the last two years, but now the tool only examines whether a person had a job at the time they were arrested.

“Even if they say, ‘Well, I lost my job,’ we’ll say, 'Were you employed at the time of your arrest?’” Martin said.

Moody said the decisions are deliberately based on what officials see in Ada County.

“We’ve been looking at it ourselves. … We’re not just going to mindlessly adopt Virginia’s tool, either,” she said.

There’s also an administrative change. The Pretrial Services Unit still surveys and interviews most people who are booked into Ada County Jail, and those IPRAI reports are still given to judges. As of Nov. 1, though, the Pretrial Services Unit will only monitor people released from jail on their own recognizance and assigned to the unit by a judge. Private companies will monitor those who pay bond and are ordered to undergo pretrial supervision.

The reason for the change, Martin said, is because the Pretrial Services Unit wants to measure the effectiveness of its own practices and changes the unit has made to how it supervises people released before trial. That shift, she emphasized, will not result in more people staying in jail.

“If we’re adding on additional supervision requirements, it’s hard to tell what’s keeping them compliant — is it the money or is it our supervision?” Martin said.

The Pretrial Services Unit can't order a defendant to go to counseling or rehabilitation, but staff can refer a defendant to those resources if people ask. They also can't give legal advice, but they are able to provide general information about the legal process and how it works.

“It’s not about an officer managing you — now it’s about a case manager helping you,” Martin said.

Chaney said he didn’t think the IPRAI was meant to harm defendants.

“I think that people have a right to be treated fairly,” Chaney said. “I think the tool was brought in with very good intentions, and I think it continues to be used with very good intentions, and that is to take human bias out … If, in fact, it does render that result, that’s great.”

More from our partner Idaho Press: ISP looking for witnesses to Monday crash on I-84 in Meridian

Watch more Crime:

See them all in our YouTube Playlist: