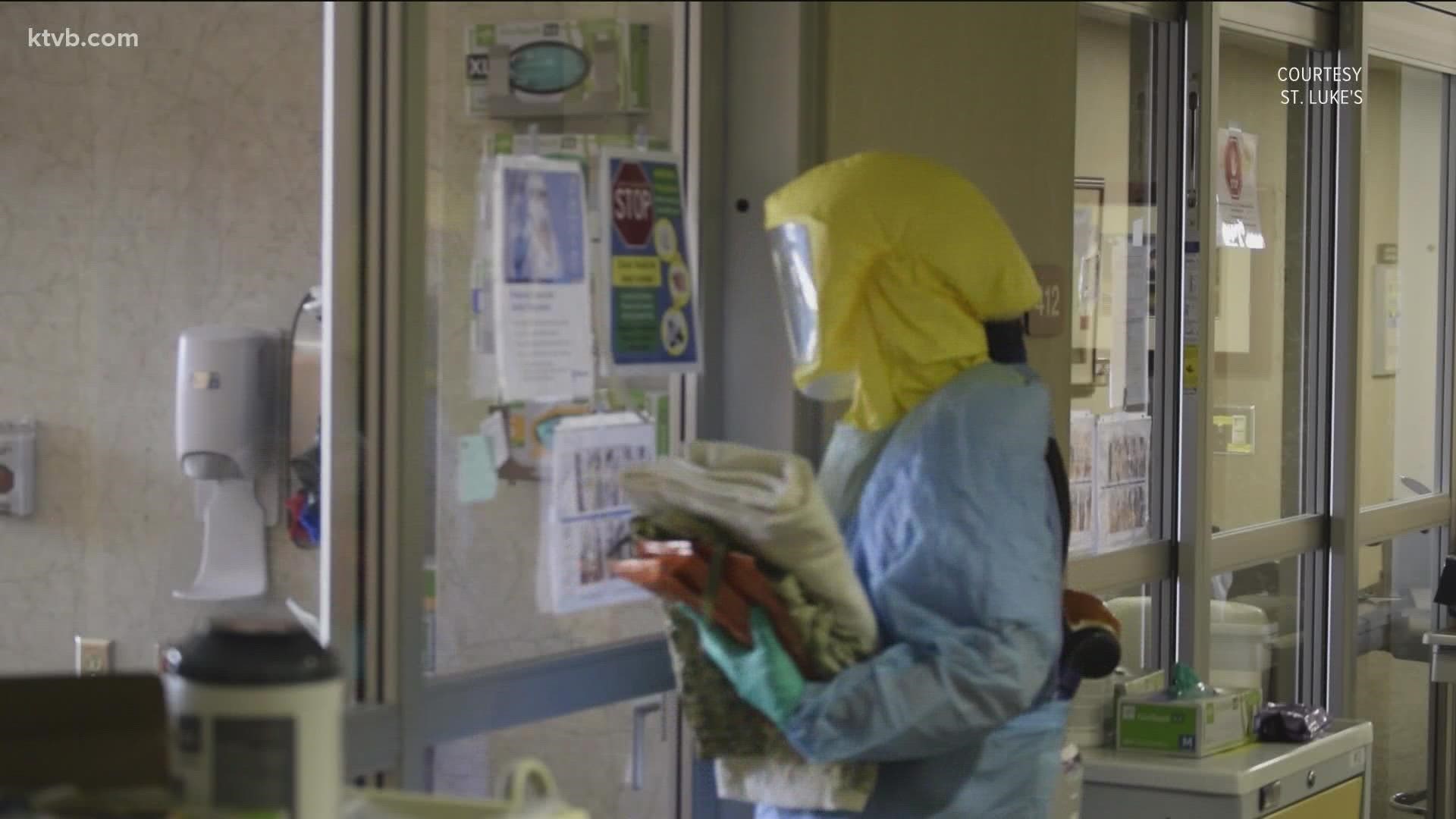

BOISE, Idaho — There is despair now, in Idaho's hospital hallways and ICU wards and waiting rooms and morgues.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, medical staff watched people pull together, staying home, wearing a mask, and fighting as one to defeat the spread of the virus.

There was hope, then, that Idaho might avoid the worst outcome: An infection rate so high and hospitals so overwhelmed by COVID-19 that doctors would be asked to make grueling choices about which of their patients will live and which will not.

That hope ended Thursday.

Following a request from St. Luke's Health System, the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare announced the expansion of crisis standards of care to the entire state, beginning the process by which medical staff, equipment, and hospital beds may now be rationed for those who are most likely to survive.

Jim Souza, Chief Physician Executive for St. Luke's, compared a hospital's normal operation to a "high wire act." In the current crisis, the scaffolding that makes that possible has fallen apart.

"The net is gone, and the people will fall from the wire," he said. "We are not able to continue to provide a conventional care standard."

At St. Luke's, people with bladder cancer, prostate cancer, and some breast cancers are being told they will have to wait for surgery to remove their tumors. People dangerously ill with sepsis are being treated in the waiting room because there are no beds available.

Patients who can't breathe without help are being ventilated by hand - with nurses squeezing a bag to force air into their lungs for hours at a time - because all the ventilators are being used on other people.

Doctors are sending COVID-19 patients that normally would be admitted to the hospital home with oxygen, prescriptions, and a set of instructions, hoping they will be able to care for themselves "when and if they deteriorate," Souza said.

"If we continue on this course, over the next several weeks, St. Luke's Health System will become a COVID health system," St. Luke's CEO Chris Roth said. "We will consume every bed and every single resource we have with COVID patients. Our ICUs are not only full, they are overflowing."

Two weeks ago, the St. Luke's hospitals hit an all-time record high of 173 COVID-19 patients. Today, that number stands at 281. Almost all of them are unvaccinated.

"This pandemic is relentless," Roth said. "We are all tired, we are all exhausted, and sadly instead of fighting this pandemic together we seem to be fighting each other."

Crisis standards act as a set of guidelines to help hospitals "under the extraordinary circumstances of an overwhelming disaster or public health emergency" to figure out how to keep as many patients alive as possible. In some areas, that will mean a long wait for a hospital bed or the chance to see a doctor; at its darkest, the designation means some very sick or badly injured people may receive only "comfort care" because the equipment that would normally be used to treat them or keep them breathing is being used for someone else.

Lack of staff is not the issue, officials said. St. Luke's has hired 802 people, more than half of whom are clinical providers, bringing them to higher staffing levels than before the latest surge in cases began earlier this summer.

The health system has also expanded overflow areas, treating patients in the catheterization laboratory, in X-ray imaging areas, in the waiting room, and in the ER in lieu of hospital rooms. The morgue has been expanded to deal with the influx of the dead.

It is still not enough, according to St. Luke's Chief Operating Officer Sandee Gehrke.

Employees are dealing with a "heartbreaking," unending level of stress as they try to keep up with the demand, she said.

"They are working ten shifts in a row, and they don't get to see their family, and they are seeing the death and the despair that COVID is bringing to us," she said. "It is really taking a toll across the board."

Not every hospital has slipped from the wire.

Chief Medical Officer Dr. Steven Nemerson said Thursday that while Saint Alphonsus Health System is in the "most extreme of contingency standards," it has not yet begun to ration care.

According to Health and Welfare, all not all hospitals will move to crisis standards of care immediately. Facilities that are managing under their current circumstances can continue to do so for as long as they are able.

Nemerson also noted that as of Thursday, no Idahoan has been removed from life support so the equipment could be given to a patient with "a better prognosis."

But that day is not far off if the rate of hospitalizations continues unabated, he said.

"I am scared," Nemerson said. "I am scared for all of us, because while we are currently able to tread water and, through the mechanisms that St. Luke's has shared with you, continue to deliver reasonable standards of care, it's going to decline simply because a caregiver can't get to a patient fast enough."

Rural hospitals, unused to a deluge of patients, are also becoming overwhelmed.

Tom Murphy, the CEO of Minidoka Memorial Hospital in Rupert, said he has long relied on the larger area hospitals to take in transfers of Minidoka patients who needed a higher level of care.

Now, he watches helicopters land at his small hospital in Rupert, carrying intensive care patients from the larger facilities where there is no room.

"We just keep trying to do what we can to keep our head above the water," he said. "We are really concerned that we will be overrun before too long as well."

Acknowledging that 18 months into the pandemic they were sounding like "a broken record," the medical leaders renewed the plea for Idahoans to get vaccinated, avoid large gatherings, wear a mask in group settings, and to trust their doctors over the misinformation on COVID-19 swirling on social media.

Just over 50% of eligible Idahoans are vaccinated, while the unvaccinated make up more than 95% of COVID-19 hospital admits.

Souza pointed to the predictive modeling doctors have used to successfully forecast looming infections and hospitalization rates. If the current trend continues, he said, 9,000 people in Idaho will become infected with COVID-19 in the next week. An estimated 300 of those will end up in the hospital. Twenty-four of them will die.

Maybe they didn't have to.

"They are 24 human beings," Souza said. "Now, I don't know their names today, but some of us around the state will come to know those 24 people's names in the 9,000 that are going to acquire it this week. And we will hold their hands, and care for them, and we will know their families. They are not a statistic."

At KTVB, we’re focusing our news coverage on the facts and not the fear around the virus. To see our full coverage, visit our coronavirus section, here: www.ktvb.com/coronavirus.

Facts not fear: More on coronavirus

See our latest updates in our YouTube playlist: